In a landmark judgment last week, the Supreme Court held that the central government’s allocation of coal blocks to public and private companies during the seventeen years between 1993 and 2010 was illegal and ultra vires the Constitution. The coal block allocation scam, popularly known as “Coalgate”, came to the forefront of the political and legal landscape when a 2012 report by the Comptroller and Auditor General (“CAG”) accused the government of causing huge losses (Rs. 1.86 lakh crore) to the public exchequer in its coal allocations. The same year, M.L. Sharma and Common Cause separately filed petitions before the Supreme Court, challenging the allocation. The petitions were clubbed together and heard jointly by the Court, which delivered its judgment last Tuesday. The political and economic ramifications of Manohar Lal Sharma v. The Principal Secretary (“Coalgate”) are already being felt. The judgment is also of great interest because of its significant contribution to one of the most important constitutional issues in contemporary India: the judicial review of the government’s distribution of natural resources.

In a landmark judgment last week, the Supreme Court held that the central government’s allocation of coal blocks to public and private companies during the seventeen years between 1993 and 2010 was illegal and ultra vires the Constitution. The coal block allocation scam, popularly known as “Coalgate”, came to the forefront of the political and legal landscape when a 2012 report by the Comptroller and Auditor General (“CAG”) accused the government of causing huge losses (Rs. 1.86 lakh crore) to the public exchequer in its coal allocations. The same year, M.L. Sharma and Common Cause separately filed petitions before the Supreme Court, challenging the allocation. The petitions were clubbed together and heard jointly by the Court, which delivered its judgment last Tuesday. The political and economic ramifications of Manohar Lal Sharma v. The Principal Secretary (“Coalgate”) are already being felt. The judgment is also of great interest because of its significant contribution to one of the most important constitutional issues in contemporary India: the judicial review of the government’s distribution of natural resources.

The Spectrum Cases – the Supreme Court’s scrutiny of process and policy

In a previous post here, I had discussed the Supreme Court’s opinions in the “2G Spectrum Cases”. In the First Spectrum Case, the Court invoked the principle of equality under Article 14, the common law doctrine of “public trust” (that is, the government acts as a trustee of the people in its ownership and distribution of natural resources), and the requirement of managing natural resources in order to serve the common good (drawn from the Directive Principles of State Policy) to hold that a public auction was the only acceptable way of distributing natural resources to private parties for exploitation. In other words, the Court not only scrutinised – and invalidated – the process by which distribution took place, but also the policy. The Court’s judgment (I argued) conflated two separate issues: the government’s obligations under the Directive Principles and the public trust doctrine, and the Court’s power (or lack thereof) to enforce those obligations. In deciding not only upon the process, but also the policy of allocation, the Court overstepped its authority in entering a field that was both beyond its competence and its legitimacy.

After the First Spectrum Case, the Court embarked upon a process of self-correction. In the Second Spectrum Case (a Presidential reference), the Court limited the holding of the First Spectrum Case only to spectrum allocation, and held that it did not lay down a requirement for public auctions being the only legitimate methods of distribution in all cases. The Second Spectrum Case left open the question, however, of the extent to which the Supreme Court could substitute its own opinions about legitimate policy for that of the government, and various observations in that case point in different directions. In Coalgate, the Supreme Court has gone a long way towards answering that question.

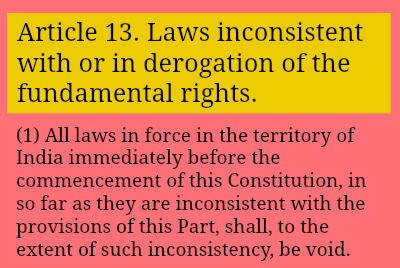

Before the Court, the petitioners contended that the coal block allocation violated statutory requirements under the Mines and Minerals (Regulation and Development) Act, 1957 and the Coal Mines (Conservation and Development) Act, 1974 as well as the public trust doctrine, and Article 14. In paragraphs 12 through 73, the Court examined the statutory question (see an analysis here), and found that the allocation was illegal. Ordinarily, this would preclude any need to examine the constitutional question. However, perhaps in view of the government’s history of amending laws retrospectively to get around court decisions, the Court then proceeded to consider the constitutional questions as well.

The Supreme Court’s refusal to second-guess government policy

The process of allocation was done by a Screening Committee constituted by the Ministry of Coal. In paragraph 82 of its judgment, the Court framed the three constitutional issues that arise for its consideration: first, whether the allocation of coal blocks ought to have been done via public auction; secondly, whether the allocations based on the Screening Committee’s recommendations were unconstitutional; and thirdly, whether the allocations made via government “dispensation” (through the Ministry of Coal) were unconstitutional. The Court settled the third question on the basis of statutory violations (paragraph 153). Therefore, we shall focus here on the first two questions. Notice that while the first question pertains to the policy of allocation (public auction versus all other methods), the second question is about the process of allocation.

The process of allocation was done by a Screening Committee constituted by the Ministry of Coal. In paragraph 82 of its judgment, the Court framed the three constitutional issues that arise for its consideration: first, whether the allocation of coal blocks ought to have been done via public auction; secondly, whether the allocations based on the Screening Committee’s recommendations were unconstitutional; and thirdly, whether the allocations made via government “dispensation” (through the Ministry of Coal) were unconstitutional. The Court settled the third question on the basis of statutory violations (paragraph 153). Therefore, we shall focus here on the first two questions. Notice that while the first question pertains to the policy of allocation (public auction versus all other methods), the second question is about the process of allocation.

The Court correctly noted that the first question required it to consider the two spectrum cases discussed above. Affirming the Constitution Bench’s opinion in the Second Spectrum Case, it noted the Central Government’s contention that the increase in input price (due to a public auction) would have a “cascading effect” upon the economy (paragraph 100), the detailed objections of the state governments (such as, for example, that auctions would lead to the concentration of industries) (paragraph 100), and the supply-demand mismatch in 1993 (paragraph 102). On the basis of these considerations, the Court held:

“[We] cannot conduct a comparative study of various methods of distribution of natural resources and cannot mandate one method to be followed in all facts and circumstances, then if the grave situation of shortage of power prevailing at that time necessitated private participation and the Government felt that it would have been impractical and unrealistic to allocate coal blocks through auction and later on in 2004 or so there was serious opposition by many State Governments to bidding system, and the Government did not pursue competitive bidding/public auction route, then in our view, the administrative decision of the Government not to pursue competitive bidding cannot be said to be so arbitrary or unreasonable warranting judicial interference. It is not the domain of the Court to evaluate the advantages of competitive bidding vis-à-vis other methods of distribution / disposal of natural resources.”

“[We] cannot conduct a comparative study of various methods of distribution of natural resources and cannot mandate one method to be followed in all facts and circumstances, then if the grave situation of shortage of power prevailing at that time necessitated private participation and the Government felt that it would have been impractical and unrealistic to allocate coal blocks through auction and later on in 2004 or so there was serious opposition by many State Governments to bidding system, and the Government did not pursue competitive bidding/public auction route, then in our view, the administrative decision of the Government not to pursue competitive bidding cannot be said to be so arbitrary or unreasonable warranting judicial interference. It is not the domain of the Court to evaluate the advantages of competitive bidding vis-à-vis other methods of distribution / disposal of natural resources.”

This is consistent with the opinion in the Presidential Reference Case, namely that an auction is required only when the aim of an allocation is to maximise revenue (because clearly, under Article 14, an auction is the only method that bears a rational nexus with an objective of revenue maximisation), but that it is open to the government to have objective other than revenue maximisation, which are also consistent with the public trust doctrine and Article 39. In this case, the Court examined the material on record, which clearly indicated that the government’s objectives went beyond direct revenue maximisation, and refused to substitute its own opinion of which policy would be most consistent with public trust and the Directive Principles. This is exactly how it should be.

Absence of relevant guidelines: Constitutional infirmity in the procedural lapses

The Court then examined the process of allocation, via the Screening Committee. In Paragraphs 109 through 151, it examined the minutes of the 36 meetings of the Screening Committee between 1993 and 2005. The Court found that in its first seventeen meetings, the Screening Committee, at no point, examined the inter se merits of the various applicant companies (paragraph 128). Even when, in its eighteenth meeting the Steering Committee did raise the question of framing guidelines for making that determination, no guidelines were actually framed (paragraph 132). And even when guidelines were framed, the Court found that they “did not lay down any criterion for evaluating the comparative merits of the applicants.” (paragraph 134) The Court noted that in its subsequent meetings, the Screening Committee made its allocations without a discussion about the inter se merits of the applicant companies (see, for example, paragraph 135, 137, 138, and 139 for specific instances), and even changed its own guidelines repeatedly (paragraph 136). In 2005, for the first time, the Screening Committee advertised for applications, but yet again, its allocations demonstrated no comparative assessment or evaluation of the applicants (see, for example, paragraphs 143, 146.1, and 148 for specific instances).

On the basis of these findings, in paragraph 150, the Supreme Court listed twenty-two procedural flaws with the allocation process, most of which had to do with the absence of any considerations about the inter-se merit between the applicant companies, the lack of any objective criteria for making that determination, and the constant changes in the norms and guidelines. Thus, in paragraph 154, the Court held:

“To sum up, the entire allocation of coal block as per recommendations made by the Screening Committee from 14.07.1993 in 36 meetings and the allocation through the Government dispensation route suffers from the vice of arbitrariness and legal flaws. The Screening Committee has never been consistent, it has not been transparent, there is no proper application of mind, it has acted on no material in many cases, relevant factors have seldom been its guiding factors, there was no transparency and guidelines have seldom guided it. On many occasions, guidelines have been honoured more in their breach. There was no objective criteria, nay, no criteria for evaluation of comparative merits. The approach had been ad-hoc and casual. There was no fair and transparent procedure, all resulting in unfair distribution of the national wealth. Common good and public interest have, thus, suffered heavily. Hence, the allocation of coal blocks based on the recommendations made in all the 36 meetings of the Screening Committee is illegal.”

It is crucial to note the Court’s assessment of the policy vis-à-vis the process. The Court upheld the non-use of a public auction as a method of distribution because, on a prima facie perusal of the material placed on record by the government, there were evident purposes behind the allocation that went beyond revenue maximisation. The Court did not substitute its own opinion of the legitimacy and validity of the purposes. On the other hand, while holding the process illegal, the Court did so on the basis that the government had placed no material to demonstrate how the allocations were made in a fair and non-arbitrary way. Therefore, much like its holding on the issue of auction, once again, the Court did not go into the question of whether the outcome of the government’s decision on allocation was valid or not, or into the merits of the guidelines; it restricted itself to the question of whether, in the process of allocation, the guidelines included essential considerations of merit and competence for deciding between applicant companies or not. It was the absence of relevant guidelines that constituted the basis of the Court’s decision, holding that the allocation was illegal.

Coalgate, therefore, represents an advance upon the route first marked out by the Court in the Second Spectrum Case. The Court will examine, for legality, the process of distributing natural resources. It will examine whether, during the process, the government has taken into account relevant considerations to ensure transparency and fairness. It will not, however – keeping in mind considerations of institutional competence and legitimacy – question the outcome of the process, or the policy behind the process.

The Court’s judgment is pragmatic and wise, and deserves to be lauded. One question remains open, however: what if the Screening Committee had prescribed guidelines for deciding inter-se merit between applicants, but the petitioners argued that the Committee’s allocation was contrary to its own guidelines? In other words, what degree of scrutiny will the Court apply to the government’s implementation of its own procedures, when disputed factual issues arise? Unlike an auction, where a violation of the results of the auction can be objectively determined, that enquiry is much harder to undertake when standards are at least partly subjective. Will the Court apply a hands-off test, taking the government’s determinations at face value, and insisting only upon the presence of guidelines (as it does, for instance, under Article 356) or a proportionality test, drawn from administrative law? Or, keeping in mind the principles of public trust and Article 39, will it subject them to a more rigorous scrutiny? Perhaps we need another Constitution bench to decide that question.

(Gautam Bhatia blogs at Indian Constitutional Law and Philosophy.)