Today would have been as good a day as any to hear the verdict of the Allahabad High Court in the Ayodhya title suit, writes Shadan Farasat.

Can two parties, who have been unable to come to a settlement for over 60 years, come to a settlement through an intervention of the Supreme Court? Two judges of the Supreme Court could not agree on an answer yesterday when they heard a Special Leave Petition to stay the impending decision of the Allahabad High Court on the title suit over the land where the Babri Masjid stood until 1992. The court eventually passed an order that abides with the Supreme Court’s tradition of issuing notice when two judges disagree on a grant of notice. The Court issued notice and granted a stay on delivery of judgment by the Allahabad High Court until September 28, 2010, when the matter is listed next before the Supreme Court. The Attorney General of India has been requested to be present in the Court for the next hearing.

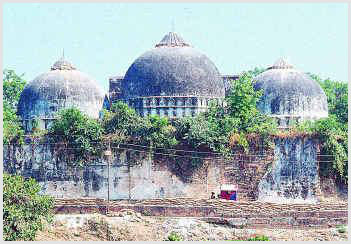

But first, some background information. The Babri Masjid, as it was called, was built by Mir Baqi in Ayodhya in 1528 on the orders of Emperor Babur. It stood there as such until December 6, 1992 when it was demolished. On January 7, 1993 the President of India issued the Acquisition of Certain Area at Ayodhya Ordinance through which 67.703 acres of the Ram Janambhoomi-Babri Masjid Complex, as it came to be called by then, was acquired by the Central Government. Existing litigation in respect of this area abated. However, the President of India, under a reference under Article 143 of the Constitution, sought the opinion of the Supreme Court on whether such action on behalf of the government would be constitutional. In Ismail Faruqui v. Union of India, AIR 1995 SC 605, a five-judge bench of the Supreme Court held that this action of the Central Government was unconstitutional to the extent it abated all pending legal disputes before courts and referred the matter to the Allahabad High Court for decision on the multiple title suits, some of which had been pending since 1949. The Supreme Court has now stayed this judgment of the Allahabad High Court until September 28, 2010.

The odds against the petitioner before the Supreme Court were indeed high. A similar request had been made before the Allahabad High Court last week, and the majority had rejected it, with costs! If the High Court does not give the decision by October 1, one of the judges, Justice D.V. Sharma, will retire and the matter will have to be heard in its entirety once again by a reconstituted bench. The new decision will take a few more years. The Allahabad High Court had already tried mediation and conciliation, but failed. The petitioner, who is one of the twenty-seven parties in the suit, also had its bona fides in question, because it had failed to actively participate in the proceedings before the High Court. Finally and most importantly, none of the other parties to the suit were willing to consider a settlement at this belated stage and political settlement by various religious leaders and as many as three former prime ministers had also failed.

So what purpose did one of the judges of the Supreme Court see in coercing the parties into another (potentially) fruitless mediation process? The only answer is the resolution – or postponement – of possible law and order problems on the delivery of the judgment, if the judgment is seen as favouring one community over the other. However, unlike in 1992, the Central Government has already taken adequate measures, and all political parties and religious groups have advised restraint and promised to abide solely by the legal process. The mood of the country is also very different from 1992. So today would have been as good a day as any other to pass this judgment. While the Allahabad High Court decision would not have resolved all the disputes in respect of the issue, particularly relating to the emotions that may be attached to it, it would have been a step in that direction. By staying the decision of the Allahabad High Court, the Supreme Court may inadvertently be providing fodder to those who want to milk the issue politically in the future. While the Supreme Court does some more thinking until September 28, the country awaits anxiously.