The Department of Industrial Policy and Promotion (“DIPP”) recently released Press Note No. 3 (2016 Series) dated March 29, 2016 (“PN3”), setting out guidelines for foreign direct investment (“FDI”) in the e-commerce space. We will look at the evolution of the law and policy on foreign investment in the e-commerce space, and in particular the scope and implications of PN3.

The Department of Industrial Policy and Promotion (“DIPP”) recently released Press Note No. 3 (2016 Series) dated March 29, 2016 (“PN3”), setting out guidelines for foreign direct investment (“FDI”) in the e-commerce space. We will look at the evolution of the law and policy on foreign investment in the e-commerce space, and in particular the scope and implications of PN3.

India’s FDI law

Foreign investment in India is governed by the Consolidated FDI Policy (“FDI Policy”) and the Foreign Exchange and Management Act, 1999 (“FEMA”) and related rules and regulations. The DIPP, which is the foreign investment regulatory arm of the Ministry of Commerce and Industry of the Government of India, makes amendments the FDI Policy by issuing press notes. Rules under the FEMA, however, are notified by the Reserve Bank of India (“RBI”).

FDI in e-commerce – the story before PN3

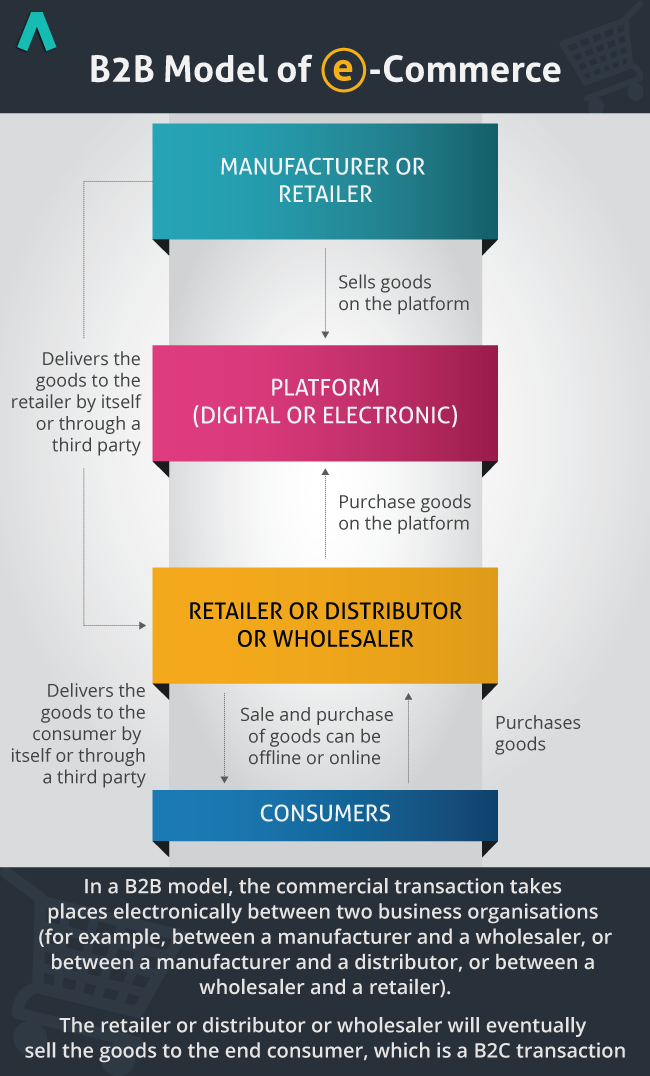

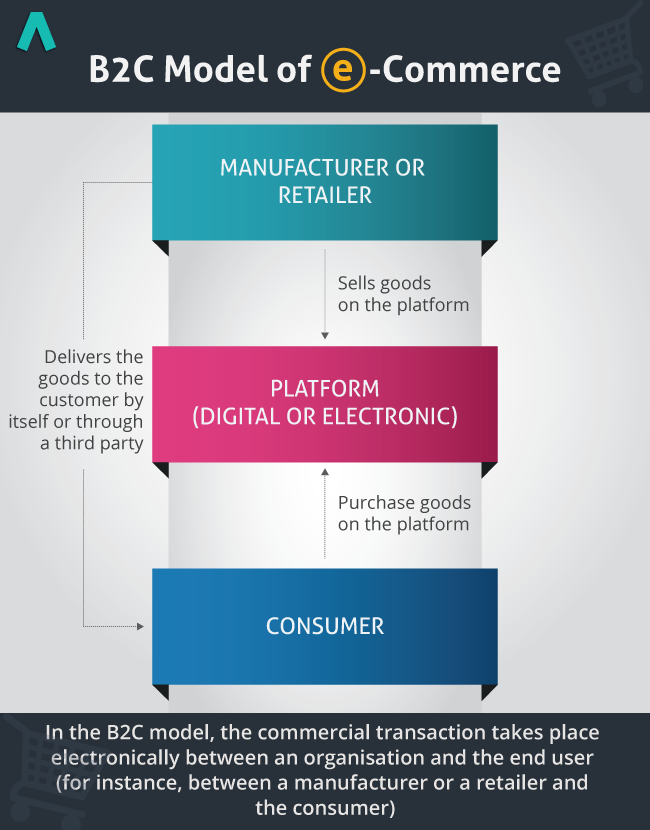

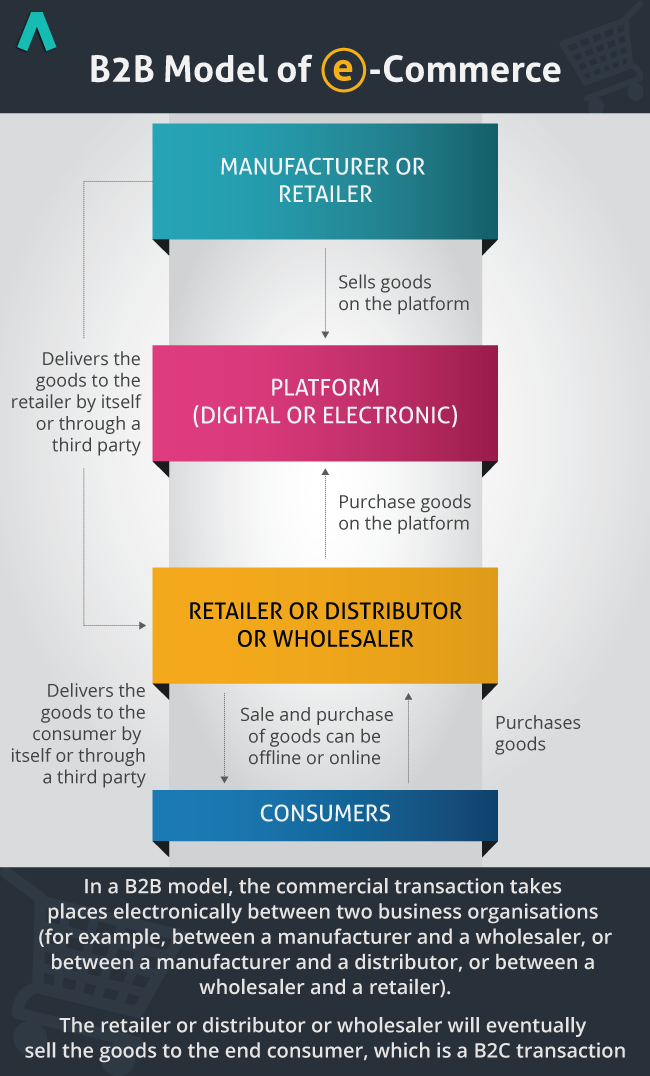

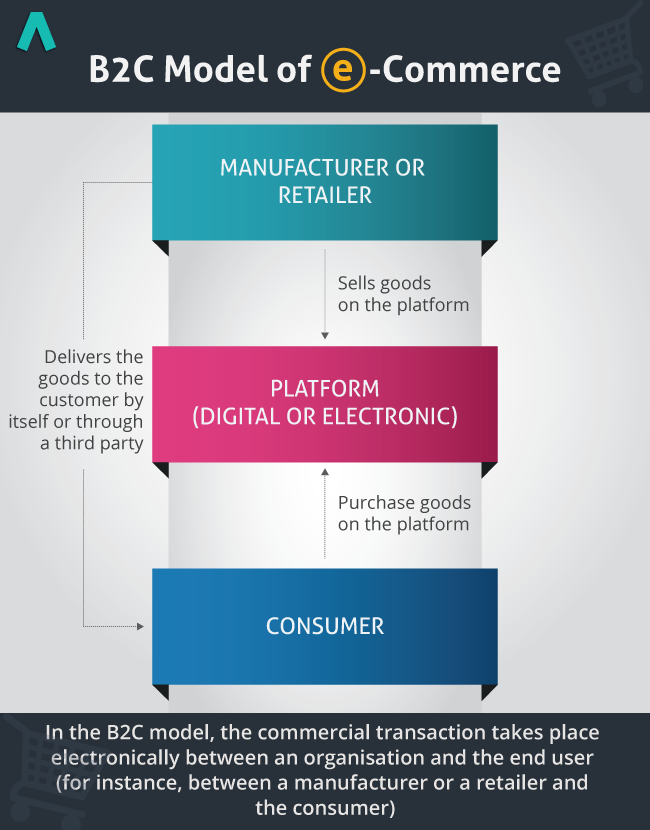

FDI has been permitted in the e-commerce space in a limited manner since the year 2000. According to Press Note No. 2 (2000 series) (“PN2”), FDI of up to 100 per cent was allowed in an e-commerce company under the automatic route (that is, without the approval of the government) as along as that company was engaged in business-to-business (“B2B”) e-commerce. If such a company was listed overseas however, 26 per cent stake in it had to be divested in favour of the Indian public within a period of five years. On the other hand, FDI was not permitted in retail trading, that is, in business-to-consumer (“B2C”) e-commerce. The policy had also categorically specified that the restrictions applicable (at that time) to domestic trading would be applicable to e-commerce as well.

On trading (including wholesale, single-brand retail, and multi-brand retail), the FDI Policy witnessed many changes since 2000, but in the e-commerce space it remained mostly stagnant until the end of 2015. Among minor changes made during this period, the requirement of mandatory disinvestment of 26 per cent stake in favour of the Indian public was dispensed with in 2006. “E-commerce” was also defined in the FDI Policy in 2010 to mean the activity of buying and selling by a company through an e-commerce platform.

In 2014, the DIPP released a discussion paper seeking comments from various stakeholders for formulating the guidelines on FDI in the e-commerce sector. While it was still in the process of formulating the policy on FDI in B2B e-commerce, it released Press Note No. 12 (2015 series) (“PN12”), which liberalised the FDI Policy in the B2C e-commerce sector in a limited manner.

Shackles on single-brand B2C e-commerce

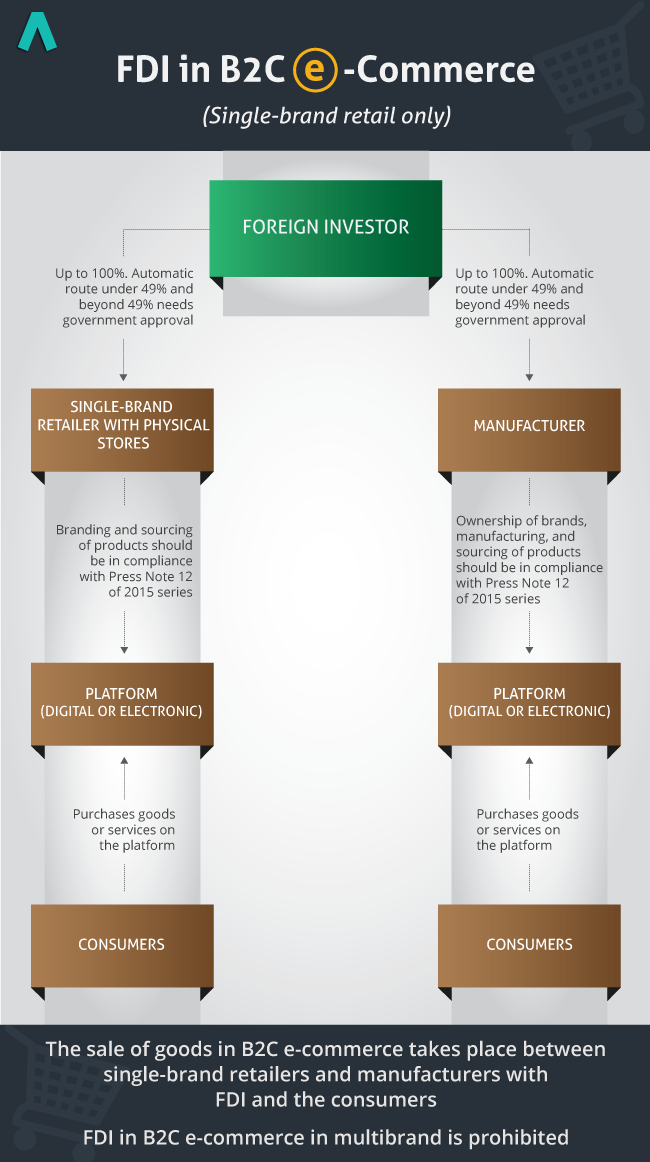

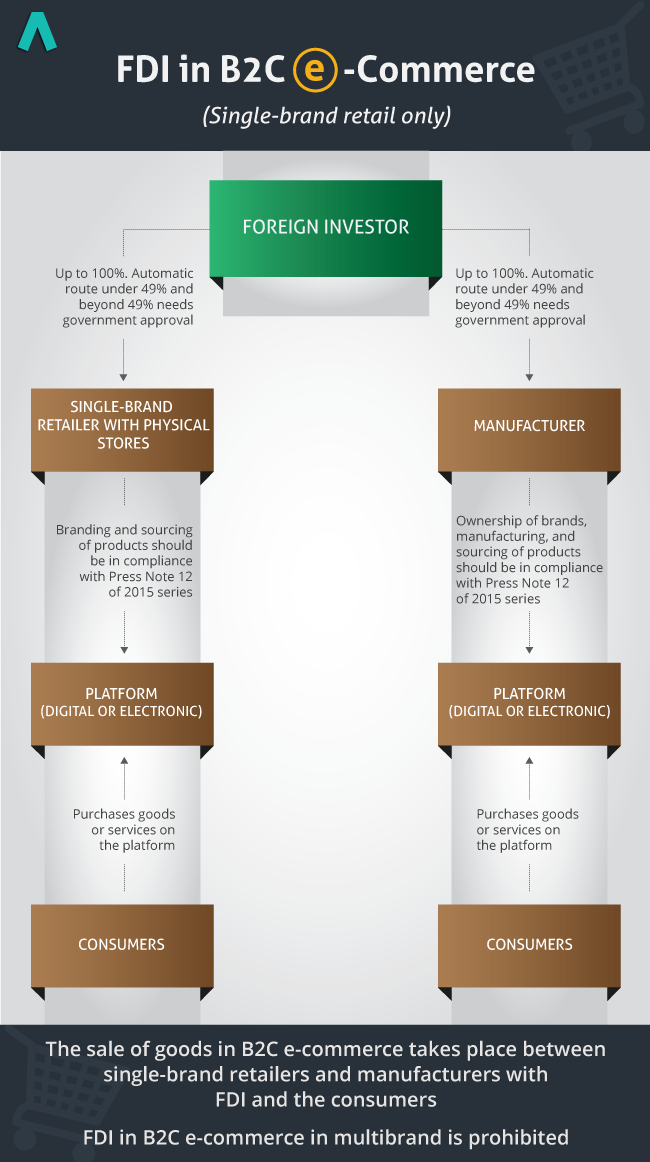

According to PN12, FDI in B2C e-commerce was permitted in ‘single-brand product retail trading’ as follows:

(a) single-brand retailers with physical stores were permitted to sell their products online as well; and

(b) Indian manufacturers were permitted to sell their own single-brand products online as along as the manufacturers are: (i) the investee companies (that is, those which have received FDI); and (ii) the owners of ‘Indian brands’ (that is, those that are owned by Indian residents or Indian companies owned and controlled by Indian residents); (iii) manufactured 70 per cent of the value of the products in-house; and (iv) sourced the remaining 30 per cent from other Indian manufacturers.

Single-brand retailers and Indian manufacturers with FDI who want to sell their single-brand products through e-commerce also need to comply with a few other conditions set out in PN12. Currently, FDI is permitted up to 100 per cent in Indian entities engaged in single-brand retail trading. FDI beyond 49 per cent requires government approval but below that threshold, it can be under the automatic route.

So far as multi-brand retail trading goes, FDI is permitted up to 51 per cent under the approval route subject to certain funding, sourcing, and other conditions. The FDI Policy on multi-brand retail e-commerce by Indian companies with FDI, however, did not change and the restriction continued by implication. Consequently, Indian companies with FDI who are engaged in multi-brand retail trade are not permitted to undertake B2C multi-brand e-commerce.

Several regulatory snarls and the litigation faced by e-commerce players during the last few years appear to have prompted the DIPP to clarify the FDI Policy on B2B e-commerce space through PN3.

PN3: Laying the boundaries for FDI in B2B e-commerce

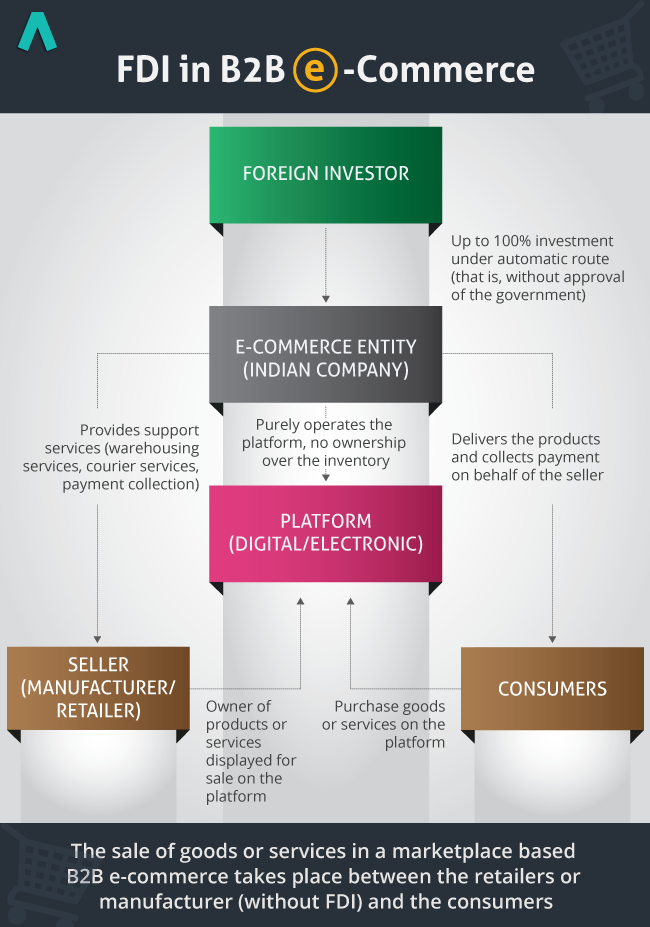

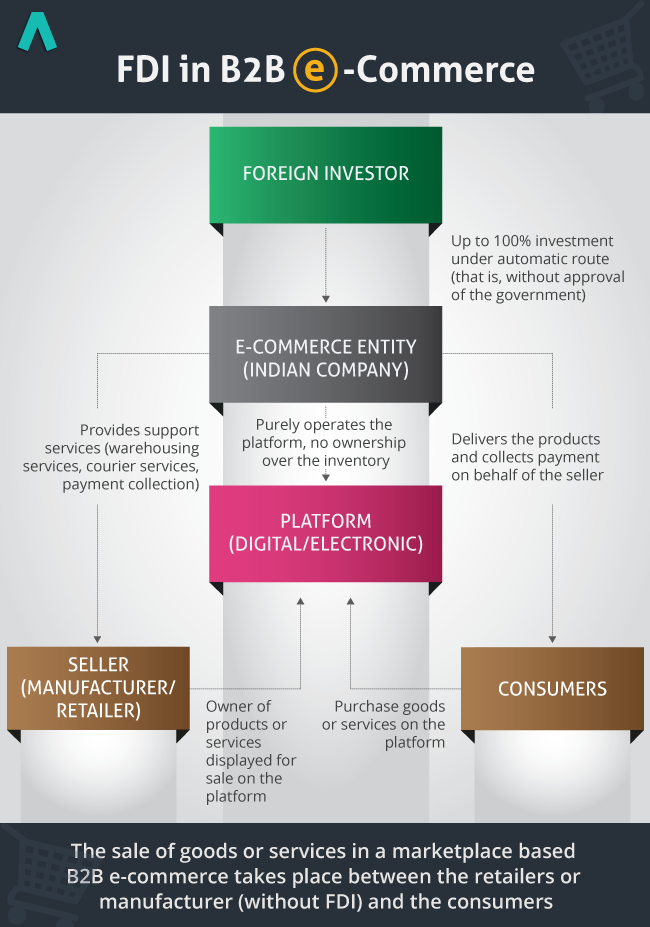

As discussed above, FDI of up to 100 per cent was already allowed in B2B e-commerce under the automatic route (that is, without the approval of the government) since 2000. PN3, in addition to reiterating the FDI policy on B2B and B2C e-commerce that is currently in place, has distinguished two models of e-commerce – the “inventory based model” and the “marketplace based model”. It clearly states that FDI of up to 100 per cent will be allowed without any government approval only in “marketplace based models” and that FDI in “inventory based models” is prohibited.

PN3 has also redefined the term “e-commerce” and clearly defined the concept of “e-commerce entities”. It stipulates some operating conditions for e-commerce entities with FDI for undertaking “marketplace based” e-commerce retailing.

“E-commerce” and “e-commerce entities”

The term “e-commerce” has been redefined to mean the “buying and selling of both goods and services, including digital products over both digital as well as electronic network”. This is broader than the previous definition, which was restricted to the buying and selling of goods by a company on an e-commerce platform. The new definition covers services also and clarifies the forms of e-commerce platforms (such as computers, television channels, webpages, and mobiles).

The term “e-commerce entity” on the other hand, has been defined for the very first time. It includes Indian companies, foreign companies, and offices, branches, or agencies owned and controlled by non-residents, which conduct e-commerce business. As a result of this new definition, it is now clear that foreign companies can invest in “marketplace based” B2B e-commerce. This will also enable foreign investors to acquire existing Indian entities operating marketplace B2B e-commerce.

It is, however, interesting that the definition does not include limited liability partnerships (“LLPs”). On a plain reading, it appears that FDI will not be permitted in LLPs that undertake B2B e-commerce. This position, however, contradicts the FDI Policy on LLPs, which was recently amended in PN12 which allowed FDI up to 100 per cent in LLPs operating in sectors where 100 per cent FDI is permitted under the automatic route and where there are no performance-linked conditions. The DIPP should provide some clarity on this front as it could impact the structuring of FDI in the B2B e-commerce space.

“marketplace based” and “inventory based”

As FDI is permitted only in marketplace-based models, it is important to understand the difference between “marketplace based models” and “inventory based models”.

The “marketplace based model” of e-commerce is defined as the provision of an information technology platform by an e-commerce entity on a digital or electronic network. A marketplace-based e-commerce entity, PN3 clarifies, cannot own any inventory by itself. If any marketplace-based e-commerce entity with FDI gains ownership over such products and services, then it will be considered an inventory-based e-commerce entity. Therefore, at no point can a marketplace-based e-commerce entity gain ownership over the goods. The title to the goods and services should remain with the seller.

A marketplace-based model is essentially a B2B model where the e-commerce entity is merely acting as a facilitator between sellers and consumers. In this model, an e-commerce entity will not sell goods or provide services directly to the consumers. The actual sale of goods or services takes place between the seller and the end consumer. The e-commerce entity will earn a commission from the seller for the services provided by it to the seller.

The “inventory based model” on the other hand, has been defined as e-commerce activity where the inventory of goods and services is owned by the e-commerce entity and those goods and services are sold directly to the consumers. An inventory-based model, therefore, is essentially a B2C model where the e-commerce entity has ownership over the goods and the sale of goods and services takes place between the e-commerce entity and the end consumer.

As we discussed above, PN12 only permitted manufacturers and single-brand retailers to undertake B2C single brand retail trading through e-commerce. If an e-commerce entity with FDI undertakes the inventory-based model, then it could be considered to be undertaking (the currently prohibited) multi-brand retail trading e-commerce.

One way to determine whether e-commerce entities are undertaking marketplace-based e-commerce is to examine the treatment of inventory or merchandise in their accounts. If they are accounting the merchandise or inventory in their own balance sheet, then they could be considered “inventory based models’ and will attract penal provisions of the applicable foreign exchange laws.

Operating guidelines for B2B e-commerce: Support functions, pricing of goods and services, and revenue generation

The DIPP has, for the first time, stipulated operating guidelines for marketplace-based e-commerce entities with FDI.

Support functions: E-commerce entities have been allowed to provide logistics, warehousing, order fulfilment, call center, payment collection, and other support functions to the sellers. These support services will allow e-commerce entities to generate revenues for themselves in addition to any commission or fee that may be charged from the seller. Leading e-commerce entities such as Amazon, Flipkart, Jabong, and Myntra provide warehousing services to sellers. As long as they are merely providing support functions to the sellers, they will not be in violation of the policy. PN3 also states that if e-commerce entities undertake payment collection, they should also ensure that their service is in conformity with the relevant RBI guidelines. These guidelines endorse the principles of a marketplace-based B2B model.

Pricing of goods and services: E-commerce entities cannot “directly or indirectly influence the sale price of goods or services” and are obligated to maintain a “level playing field”. This guideline has been seen as a measure to curb the predatory pricing tactics of e-commerce entities and to create a level playing field with offline traders. There have been allegations that leading e-commerce players, in order to attract customers on the platform, are using innovative methods to influence sellers to substantially mark down prices or provide deep discounts on their products and services. For example, some e-commerce entities such as Amazon refund the amount denoting discounts provided by the sellers on the platforms. Some e-commerce players like Patym provide cash back on the products purchased on the platform to the consumers. In a true marketplace-model however, sellers are in control of the pricing of the products and services, and any markdown or discounts on the maximum retail price on the platform are offered directly by the sellers. The e-commerce entity, which is merely a facilitator between the sellers and the consumers, does not influence the pricing of products and services offered by the sellers on the platform in any way.

While PN3 does not explain the parameters for determining “influence”, this guideline is expected to impact offline arrangements (such as the funding of discounts) between sellers and e-commerce entities as they may be considered to amount to influencing sale prices. Despite this regulation, many e-commerce websites continue to provide discounts and cash back offers. The pricing models adopted by sellers and e-commerce entities will need to be studied in greater depth to determine if e-commerce companies are in violation of this provision. The DIPP should clarify the intent of this provision to ensure that e-commerce companies with FDI are not violating this guideline.

Sourcing: E-commerce entities cannot derive more than 25 per cent sales on their platform from a single seller or any of the e-commerce entity’s group companies. This guideline is intended to ensure that e-commerce entities do not carry out B2C e-commerce in the garb of a marketplace model using convoluted business structures. This provision will definitely impact those e-commerce players who derive more than 25 per cent of their sales from their vendors or group companies. For instance, it is reported that both Flipkart and Amazon India generate sales beyond 25 per cent from their group companies, WS Retail Services Private Limited and Cloudtail India Private Limited, respectively. These e-commerce players will need to restructure their business models to toe the line with PN3. Further, there is no clarity on the duration for calculating the cap on sales, that is, whether this cap will be calculated on a financial year basis or otherwise. The DIPP should also clarify the intent of this provision to ensure that e-commerce companies with FDI are not violating this guideline.

Other conditions: The responsibility for the delivery of goods to the customer and customer satisfaction following a sale on the technology platform as well as providing any warranty or guarantee of goods and services lies with the seller. This guideline is in line with the principles of a marketplace-based model. If such responsibility lies with the e-commerce entity, then it will no longer be considered a mere facilitator, and any sale on its platform could take on the colour of B2C multi-brand e-commerce retail, which (as we have discussed previously) is currently prohibited, except for single-brand retailers and manufacturers.

The guideline on the delivery of goods by the seller, however, appears to contradict the guideline which allows e-commerce entities to provide support services to the sellers. This may be a drafting flaw, which the DIPP will need to clarify to ensure that e-commerce companies with FDI are not violating this guideline.

PN3 also states that e-commerce entities are permitted to enter into transactions with sellers registered on the platform on a B2B basis. This guideline is very ambiguous since it does not clarify what kind of B2B business e-commerce entities are expected to transact with sellers on. For example, if the sellers sell their goods to e-commerce entities, it would be considered as a B2B business since e-commerce entities are not the ultimate consumers. This would, however, violate the guideline that e-commerce entities gaining ownership over the goods will no longer be considered marketplace-based e-commerce entities. This ambiguity needs to be clarified by the DIPP.

Going forward – the search for a level playing field

The introduction of PN3 may encourage foreign investors, who may have been hesitant to enter this space till now due to a lack of regulatory clarity, to invest in the Indian e-commerce space. It also provides legitimacy to the existing businesses of e-commerce companies with FDI that have been operating on the marketplace model in India. E-commerce companies with FDI will definitely need to re-examine their business structures to ensure that they are in compliance with PN3.

Having said that PN3 may not really create a level playing field between e-commerce entities with FDI and e-commerce entities without FDI. PN3 could impact e-commerce companies that already have FDI or intend to raise FDI, but not e-commerce companies without FDI. While the FDI Policy will govern only those e-commerce companies with FDI, no similar restrictions apply to e-commerce companies without FDI under other laws. The latter category may, for instance, continue to provide deep discounts on similar products and services or generate revenues beyond 25 percent from a single vendor or group company. Further, there are no similar restrictions on offline retailers without FDI. The government, which is keen on attracting foreign investment in this sector, should re-examine this policy to ensure that the interests of both offline retailers as well as e-commerce entities are adequately protected. While PN3 is a good move, there is room for further fine-tuning a few aspects of the policy by the government, especially with respect to the pricing of products and services and limits on revenue generation.

Swetha Prashant is a Principal Associate at J. Sagar Associates. Divya Sinha is a Junior Associate at the same firm. The views expressed in this article do not represent the firm’s view in any manner.

In the dawn of demonetisation, most of us have found ourselves adapting to new payment mechanisms and methods. The government’s strong push towards a cashless society seems to be ushering in the age of the e-wallet. Paytm alone is responsible for more transactions per day than the combined average daily usage of all the debit and credit cards in India. Mobile wallets, which many of you are using these days, are a type of pre-paid instrument. But what are pre-paid instruments? How do they work?

In the dawn of demonetisation, most of us have found ourselves adapting to new payment mechanisms and methods. The government’s strong push towards a cashless society seems to be ushering in the age of the e-wallet. Paytm alone is responsible for more transactions per day than the combined average daily usage of all the debit and credit cards in India. Mobile wallets, which many of you are using these days, are a type of pre-paid instrument. But what are pre-paid instruments? How do they work?

Abhishek is a legal and business strategy consultant with ePaylater, one of India’s first one- click checkout payment solutions. This article should not be construed as legal advice. The views expressed in this article are his personal views and opinions. He can be reached at abhishek.ray@epaylater.in.

Abhishek is a legal and business strategy consultant with ePaylater, one of India’s first one- click checkout payment solutions. This article should not be construed as legal advice. The views expressed in this article are his personal views and opinions. He can be reached at abhishek.ray@epaylater.in.

The Department of Industrial Policy and Promotion (“DIPP”) recently released

The Department of Industrial Policy and Promotion (“DIPP”) recently released