Declaring Independence is a series by Tishampati Sen, an Advocate-on-Record who quit his job at a top-tier law firm to start his own practice. Setting up one’s own practice at a relatively young age is a challenge, albeit one that can have great rewards. Every month, Tishampati will look at an important aspect of going independent and have useful tips and advice for young lawyers who just want to break free! Read the previous post here.

I knew at the time of taking my first steps towards independent practice, that one of the formidable challenges in front of me would be of generating enough work to make a living. One of my greatest apprehensions at the time of making the move was that I might have to sit idle for many months before people would actually entrust with work. From the very beginning, therefore, I associated with and assisted eminent senior counsel and other advocates in their work so as to be ‘in – practice’ even while my independent work gathered momentum

But from very early on, in fact even before I had completely quit the firm that I was a part of, I had started pitching for work and trying to impress upon people the fact that a new hotshot lawyer was soon going to be available to take care of all their legal needs.

DRAWING A BOUNDARY

One of the key questions that people would ask me is “so what kind of work do you do?” and my immediate response would be “Everything”. But invariably the person would continue to look at me expectantly waiting for me to say something more, before finally nodding and uttering a dismissive “good”. But I didn’t know a better answer at the time. I was actually preparing myself to do all sorts of legal work. I had both transactional as well as dispute resolutions experience and intended to do both kinds of work in the future as well. Over a period of time, immediately after my “Everything”, I decided to add, “I do both litigation as well as transactional work” to fill the awkward silence. But to my surprise I was still met with a glazed look.

One of my more experienced colleagues heard my response one day and decided to rescue me. He let me in on a little secret. “Branding is important. People don’t like to believe that ‘everything’ is possible. Give them a boundary and a framework. When you give them your limitations, your capabilities also become believable; and if you haven’t discovered your limitations yet, invent them.”

This is one of the most important and beautiful lessons in human psychology for me. I am not sure if I completely believed it at the time, but the next time some one asked about the kind of work I do, my answer was a little more tempered. I still told them that I do everything but I also added an ‘except…’ and told them one or two things that I don’t do; or what I haven’t done yet – but was willing to do if the opportunity presented itself. Surprisingly, there were many more people now nodding and moving forward with the conversation. In fact, there were even some who would discount my ‘limitation’ and say “Yes, but after all it’s only another branch of law. If you study it, I’m sure you’ll pick it up.”

FACTORS GOVERNING THE CHOICE OF WORK

There could be a few factors that could govern the kind of matters/work that one may want to source and take up at this stage:

1. Streams: There are some who, like me, enjoy both streams of practice and therefore may actively look to do all sorts of work in both transactional–advisory practice, as well as in litigation. In fact from my experience, the learnings in one could even help your develop your skills in the other. For example, the litigation experience and the understanding of the courts and the processes involved has helped me develop a different perspective on the language used in contracts. I now have an understanding that clauses that may seem air–tight in language may be looked at in a completely different context in court. As such, the advice on the transactional side is now more pragmatic than theoretical. Similarly the experience on the transactional side helps in grasping complex transactions better and may, therefore, allow one to articulate the issues involved much better in court.

However, there are also those who would much rather focus on any one stream (and within that, a sub-stream) to be able to build a brand and expertise in the subject. One cannot deny that in this field where a client’s interest and sometimes life is at stake, how the world perceives you may become relevant. Some time back when a friend needed legal representation for a family member who had unfortunately been tangled up in criminal proceedings, he was very clear that he wanted a ‘pure’ criminal lawyer. Not someone who also practiced criminal law. Similarly in sensitive matters such as divorce etc., parties may be more comfortable with an advocate who shows herself to have expertise in that field.

2. Forum of Practice: This is more relevant for the litigation side of the practice, as often advocates may also target work keeping the forum in mind. There are those who may have a wider network outside the city/state, as such it may make sense to consider appellate forums. The choice of the forum could also be impacted by various other considerations such as the kind of work that one enjoys (trial matters, versus consumer matters, tax etc.), the clientele typically associated with a particular forum, the regularity of proceedings in the forum, or simply what interests you more etc. Here again there could be the debate for specialisation versus exploration. I know of many young advocates who have focused on the practice in a few particular forums. Over a period of time they have developed a better understanding of the processes and the requirements in the registry and are able to better fathom the tendency and mood of the bench. These advocated then become much more in demand in these particular fora. However, on the flip side one may want to practice in various fora and over a much longer period have a much wider presence. In fact some might argue that having matters in various fora and the thrill of appearing before different judges with different opposing counsel is what makes the litigation practice exciting.

3. Realistic Evaluation of Reference of Work: Another perspective to keep in mind, while considering the kind of work that one may want to attract, is what would make sense in terms of being able to develop clientele. For example, as a young advocate it may make sense to spend as much time observing and assisting on trial matters, consumer matters, divorces etc., since the potential to have this nature of matters being referred to you by individual clients is much higher when on your own.

Even on the transaction front, it may make sense to initially focus on the kind of work that could lead to repeat requests and referrals by clients. For example focus could be on the issues facing start–ups that have great need for legal advice but may not have the budget to approach the established and eminent legal practitioners. Focusing on the individuals or smaller business units in the beginning may be a prudent starting point.

CURB YOUR ENTHUSIASM

A common and popular advice seems to be that a junior advocate must be willing to take whatever work comes his way. Saying no to any work, no matter how tedious or boring it might seem, is almost sacrilegious. It makes sense of course – you must be willing to take the good with the bad, and only when you have had a varied and diverse experience can you even begin to identify your own unique strengths and weaknesses and likes and dislikes. In fact, a bit of a push and pressure may even help develop character and create the mettle to take up challenges. So the general idea is that one should never say no to work, and once accepted one must figure out the capacity and the wherewithal to handle the same.

However, there was one person who gave me contrary advice, which also made a lot of sense. This gentleman who has a thriving criminal practice, told me, over a cup of coffee, “it is equally important to curb your enthusiasm.” His point was that at the beginning of one’s independent practice, a junior advocate/lawyer must focus on work as much as self–development. “Eventually you have to start keeping in mind the balance–sheet, and focus on managing your office. Things like the supply of coffee for clients, printer cartridges, wages, etc., also start taking up your time. So value this time in the beginning. Now is the time to develop the lawyer within. Keep the businessman waiting for a while. Appreciate that since for now there is less work, you should read the law for the sake of reading the law. Sooner or later work will find you.”

He also warned me that taking up more than can be handled in the beginning could be more detrimental than not having enough work. If you tell a client frankly that you may not be able to handle his work, you may lose her/him temporarily. But servicing a client badly could lead to the loss of not just that client but many future clients as well. He called it “poisoning the line”, which had a nice dramatic ring to it and so it has stuck with me.

To close off this piece, I would like to remind you of what I had said in the beginning of this series: I am not qualified to give you advice as to your specific way forward. My only aim is to share my experiences and the views that others have selflessly and candidly shared with me. So, choose the viewpoint that suits you and your temperament best. See you next time!

Tishampati Sen is an Advocate–on–Record of the Supreme Court of India. He worked with one of the premier law firms of the country (in corporate transactions as well as dispute resolution) for many years before deciding to take the plunge of independent practice. He appears primarily before the Hon’ble Supreme Court of India, Delhi High Court and the National Consumer Disputes Redressal Commission.

Declaring Independence is a series by Tishampati Sen, an Advocate-on-Record who quit his job at a top-tier law firm to start his own practice. Setting up one’s own practice at a relatively young age is a challenge, albeit one that can have great rewards. Every month, Tishampati will look at an important aspect of going independent and have useful tips and advice for young lawyers who just want to break free!

Declaring Independence is a series by Tishampati Sen, an Advocate-on-Record who quit his job at a top-tier law firm to start his own practice. Setting up one’s own practice at a relatively young age is a challenge, albeit one that can have great rewards. Every month, Tishampati will look at an important aspect of going independent and have useful tips and advice for young lawyers who just want to break free!

In the dawn of demonetisation, most of us have found ourselves adapting to new payment mechanisms and methods. The government’s strong push towards a cashless society seems to be ushering in the age of the e-wallet. Paytm alone is responsible for

In the dawn of demonetisation, most of us have found ourselves adapting to new payment mechanisms and methods. The government’s strong push towards a cashless society seems to be ushering in the age of the e-wallet. Paytm alone is responsible for

Abhishek is a legal and business strategy consultant with

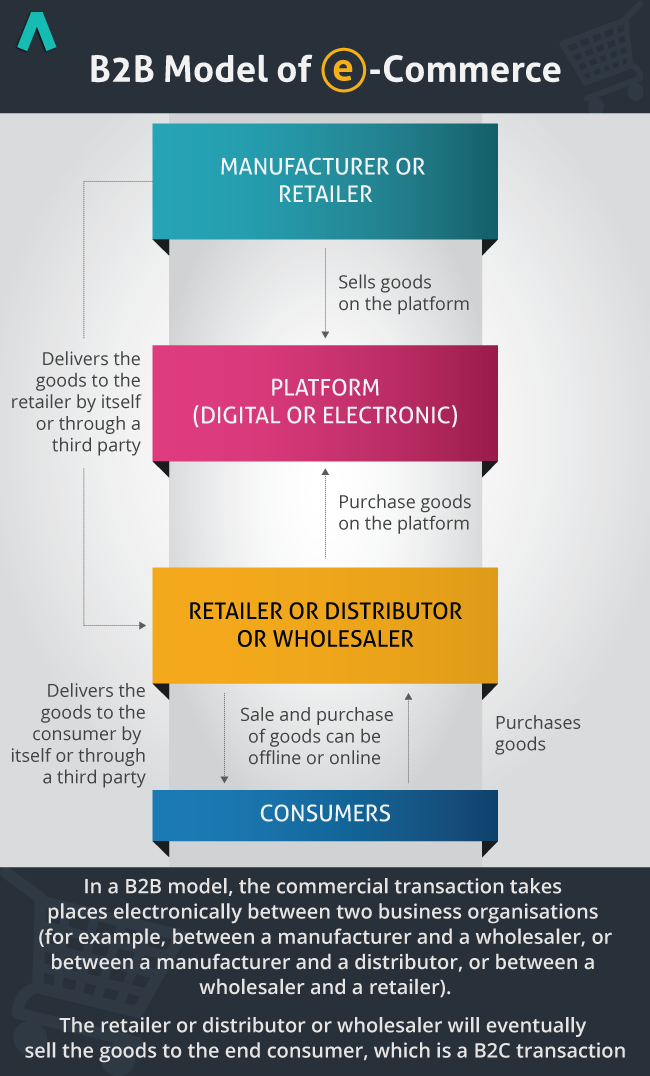

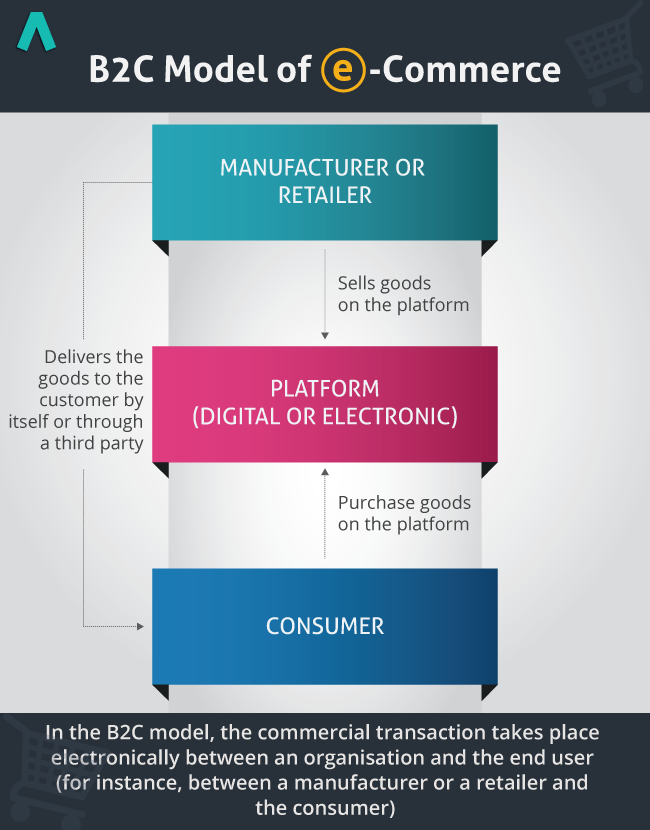

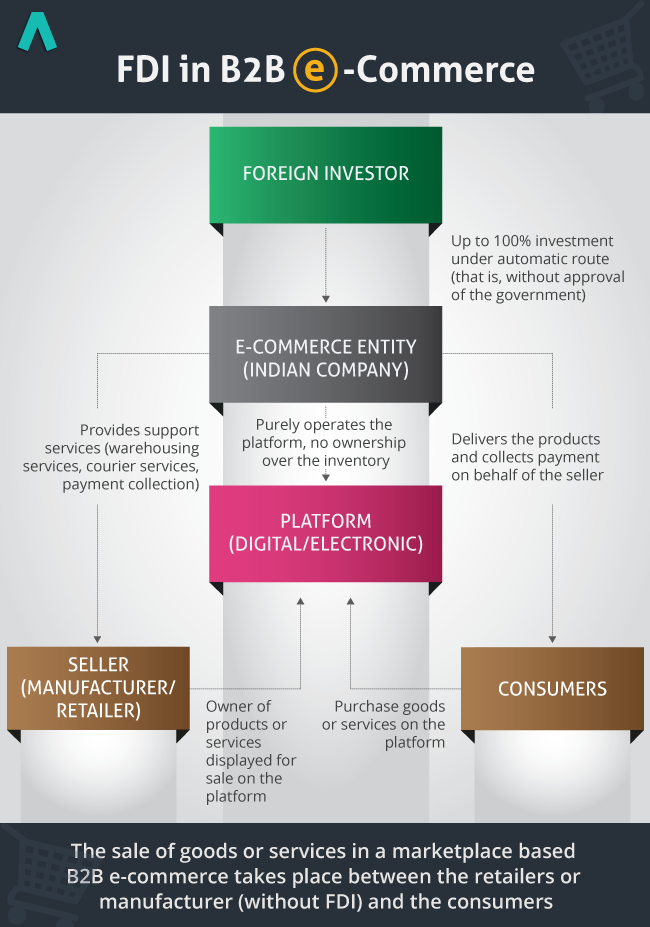

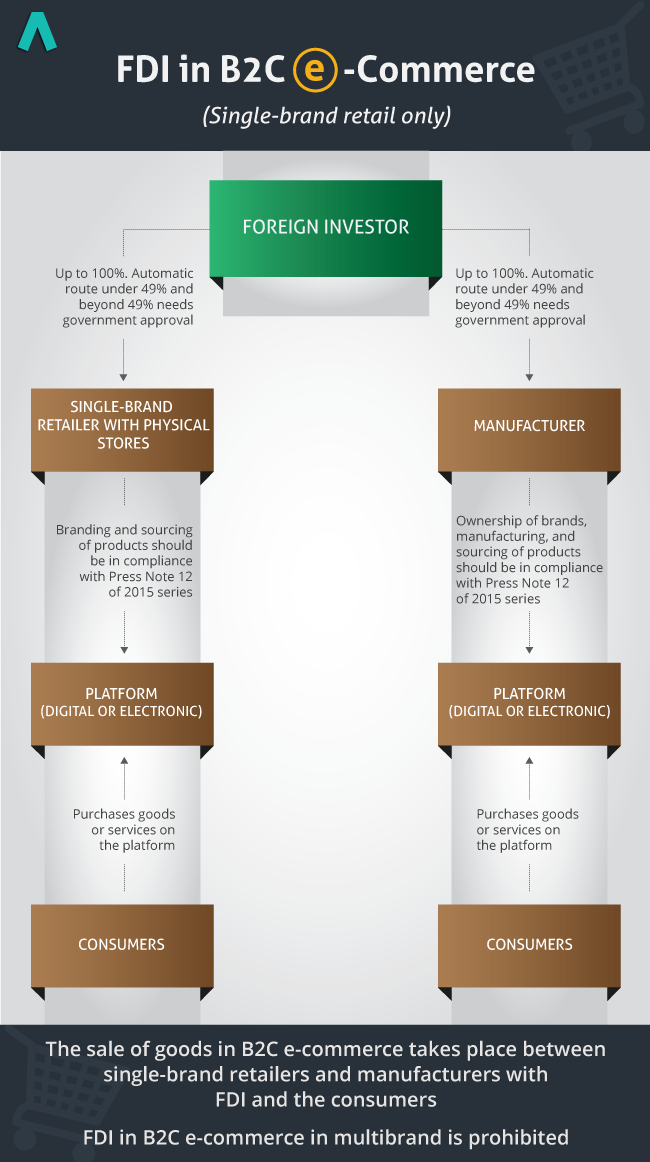

Abhishek is a legal and business strategy consultant with  The Department of Industrial Policy and Promotion (“DIPP”) recently released

The Department of Industrial Policy and Promotion (“DIPP”) recently released