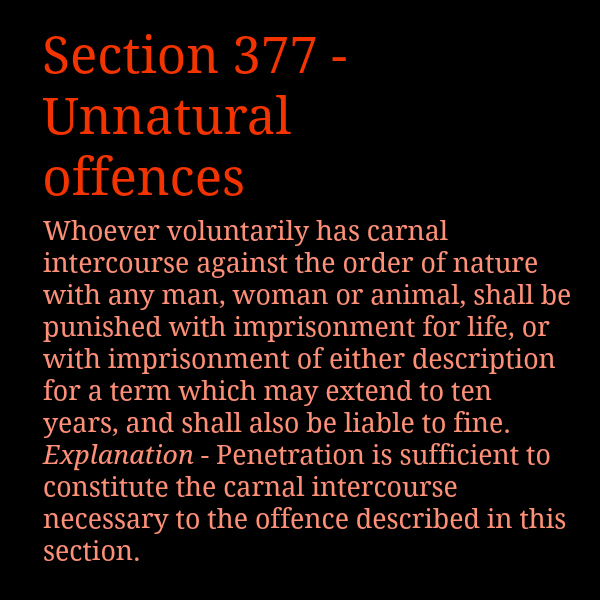

We need to get rid of two red herrings that have captured at least some of the debate that followed the Supreme Court’s decision in Suresh Kumar Koushal and Another v. NAZ Foundation and Others. The first is the issue of the presumption of constitutionality of the Indian Penal Code, 1860 (“IPC”) and the second relates to whether the Court characterised the Delhi High Court’s judgment as an instance of judicial overreach.

We need to get rid of two red herrings that have captured at least some of the debate that followed the Supreme Court’s decision in Suresh Kumar Koushal and Another v. NAZ Foundation and Others. The first is the issue of the presumption of constitutionality of the Indian Penal Code, 1860 (“IPC”) and the second relates to whether the Court characterised the Delhi High Court’s judgment as an instance of judicial overreach.

The question of presumtion of constitutionality

The rule of presumption of constitutionality of laws is that when any law is under judicial review, it is for the person challenging its constitutionality to establish its unconstitutionality. It is a rule of procedure applicable to cases in which the constitutional validity of a law has been called into question. It is not a substantive rule. If the law is not shown to be unconstitutional, its validity will be upheld. Conversely, the presumption of constitutionality is rebuttable, and it does not prevent a law from being declared unconstitutional.

The presumption of constitutionality of a law does not mean that a law is actually constitutional any more than the presumption of innocence until proof of guilt in criminal cases means that a person accused of a crime is actually innocent — it only means that the task of proving guilt lies on the prosecution.

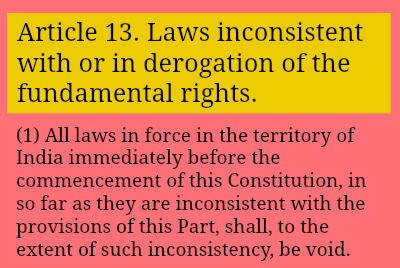

There is little controversy about the rule of presumption of constitutionality applying to laws made after the Constitution of India came into force. However, the IPC (including Section 377) is a pre-Constitution law. The High Court stated (Paragraph 105 of its judgment) and others have argued that the presumption of constitutionality of laws does not or ought not to apply to pre-Constitution laws, primarily because the colonial law could not possibly have anticipated the requirements of constitutional validity.

To the contrary, in Madhu Limaye v. Sub-Divisional Magistrate, (1970) 3 SCC 746, at page 753, a seven-judge bench of the Supreme Court has held:

“Pre-constitution laws are not to be regarded as unconstitutional. We do not start with the presumption that, being a pre-constitution law, the burden is upon the State to establish its validity. All existing laws are continued till this Court declares them to be in conflict with a fundamental right and, therefore, void. The burden must be placed on those who contend that a particular law has become void after the coming into force of the Constitution by reason of Article 13(1), read with any of the guaranteed freedoms.”

According to Article 395 of the Constitution, two pre-Constitution laws that were obviously at odds with the Constitution were expressly repealed – the Indian Independence Act, 1947, and the Government of India Act, 1935. According to the Article 372, laws in force prior to the commencement of the Constitution shall continue in force, subject to the other provisions of the Constitution, until altered or repealed. This should be read with Article 13(1), which makes pre-Constitution laws void “in so far as they are inconsistent with the provisions of [Part III – Fundamental Rights]”. This constitutional stricture applicable to pre-Constitution laws applies in analogous terms to post-Constitution laws, by virtue of Article 13(2).

The standard for validity of laws remains the same, whether the law in question is a pre-Constitution law or a post-Constitution law. Therefore, if Parliament does not repeal a law (such as Section 377, IPC), it remains in force by virtue of Article 372, unless its unconstitutionality is established. It bears reiteration that the presumption of constitutionality does not imply that Section 377 is actually constitutional any more than the presumption of constitutionality implies that any post-Constitution law is actually constitutional.

If the presumption of constitutionality does not apply to pre-Constitution laws, two anomalies arise.

– Firstly, there is no reason for anyone to consider themselves bound by any provisions of a law such as the IPC (which also criminalises murder, for instance), unless those provisions are declared constitutional. Not having a presumption of constitutionality is another way of saying that the law is not valid until found to be so by the Supreme Court or any high court.

– Secondly, many pre-Constitution laws still in force today are relatively innocuous – for instance, the Indian Contract Act, 1872, the Transfer of Property Act, 1882, the much-loved Code of Civil Procedure, 1908, and a substantial chunk of the law of tort (not all pre-Constitution laws are in the form of statutes). Is there any reason these laws should not have the presumption of constitutionality?

The Supreme Court in this case was correct to state that the presumption of constitutionality applies to Section 377. The error, as far as this issue is concerned, was in then stating (in Para 32 of the judgment):

“While [the presumption of constitutionality] does not make the law immune from constitutional challenge, it must nonetheless guide our understanding of character, scope, ambit and import.”

The phrase ‘character, scope, ambit and import’ appears to refer to the constitutional challenge. In other words, the presumption of constitutionality appears to erroneously guide the understanding of the question of the validity of the law, as if the presumption is a self-reinforcing one. A procedural rule was allowed to have a substantive impact. The presumption is only a rule of procedure meant to indicate that the party challenging constitutionality must establish it to succeed.

The phrase ‘character, scope, ambit and import’ appears to refer to the constitutional challenge. In other words, the presumption of constitutionality appears to erroneously guide the understanding of the question of the validity of the law, as if the presumption is a self-reinforcing one. A procedural rule was allowed to have a substantive impact. The presumption is only a rule of procedure meant to indicate that the party challenging constitutionality must establish it to succeed.

The fact that Parliament has not interfered with Section 377 only means that the presumption of constitutionality is applicable to it, not that the law, by virtue of having implied popular approval, is somehow more likely to be constitutionally valid. Popular approval has no relevance to Article 13. The question of whether a law is consistent with fundamental rights has to be decided by analysing the law with reference to those fundamental rights, and not by looking at how many people (presumably) support that law. The Constitution guarantees fundamental rights and democracy, not fundamental rights subject to democracy.

Did the Supreme Court characterise the High Court judgment as a case of judicial overreach?

Two or three passages from the Supreme Court’s judgment appear to have created an impression (especially prior to the publication of the full judgment online) that the main reason for setting aside the judgment of the High Court was the doctrine of separation of powers, with the Court acknowledging that interpreting Section 377 as unconstitutional would be an instance of judicial overreach. These passages perhaps were:

“In fact a constitutional duty has been cast upon this Court to test the laws of the land on the touchstone of the Constitution and provide appropriate remedy if and when called upon to do so. Seen in this light the power of judicial review over legislations is plenary. However, keeping in mind the importance of separation of powers and out of a sense of deference to the value of democracy that parliamentary acts embody, self-restraint has been exercised by the judiciary when dealing with challenges to the constitutionality of laws.” (Paragraph 26)

“In its anxiety to protect the so-called rights of LGBT persons and to declare that Section 377 IPC violates the right to privacy, autonomy and dignity, the High Court has extensively relied upon the judgments of other jurisdictions.” (Paragraph 52)

“Notwithstanding this verdict, the competent legislature shall be free to consider the desirability and propriety of deleting Section 377 IPC from the statute book or amend the same as per the suggestion made by the Attorney General.” (Paragraph 56)

By describing the interpretation by the High Court of Section 377 as “legally unsustainable”, the Supreme Court has impliedly endorsed the previous interpretations of Section 377, as a result of which any carnal intercourse other than penile-vaginal sex is classified as ‘against the order of nature’. Admittedly, this position of law was a result of judicial interpretation, which is certainly not beyond the scope of the Supreme Court.

While deference to legislative preference may appear to be part of the overall reluctance to uphold the judgment of the High Court, adjudication upon the core issues of the constitutional validity of Section 377 vis-à-vis Articles 14, 15, and 21 was unavoidable. The judgment of the Supreme Court is unambiguous in concluding that in substance, Section 377, as interpreted prior to the judgment of the High Court, does not violate the Constitution.

(The previous parts of this article are here and here.)

(Aditya Verma practices as an Advocate at the Supreme Court of India. He is an alumnus of NLSIU, Bangalore, and is on the roll of solicitors in England and Wales.)