Contrary to popular belief, the Indian Constitution is not the longest written constitution in the world. That distinction goes to the State of Alabama whose colossal constitution laughs at our constitution’s puny 117,369 words, roughly one-third of its (Alabama’s) 340,136. But, inappropriate “size matters” jokes aside, India does have the longest national constitution in the world and that means that even in the single most important document in our country, some provisions tend to get lost or ignored until the need to invoke them arises.

Clearly, the superstars among the 488 Articles in the Indian Constitution are the ones contained in Part III – the Fundamental Rights, the cornerstone of our democracy, carefully and lovingly gathered by the drafters of our Constitution from such epochal, paradigm-shifting documents as England’s and U.S.’s Bills of Rights and France’s Declaration of the Rights of Man. You could say our Fundamental Rights were more than 250 years in the making, the culmination of enlightenment and the humanist awakening after the dark ages.

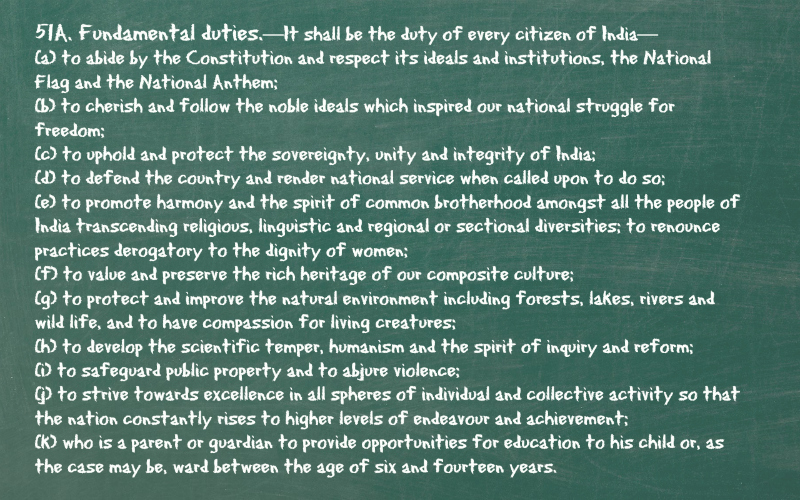

Comparatively then, the Articles contained in Part IV-A of our Constitution are young upstarts, Johnnies-come-lately, having been inserted into the Constitution twenty-six years after it came into effect. Fundamental Duties? Seriously, who cares? They aren’t even legally enforceable. Ask lawyers or law students about our Fundamental Rights, and they will rattle off the whole list, perhaps verbatim, along with case citations. Ask them about the Fundamental Duties and you will be met either with perplexed expressions or quick dismissal.

I mean come on, reading Article 51-A is like getting a short lecture on how to live your life by a slightly preachy granduncle who was alive during the British Raj. The language is vaguer than 2004’s ‘India Shining’ campaign. For example, “to cherish and follow the noble ideals which inspired our national struggle for freedom”? What does that really mean? Let’s be honest with ourselves, different people had different motivations to fight for our independence, and while most of them were noble, there were some who wanted the freedom to create a Hindu mega-state, others who wanted partition, there were vested interests, political games, and intrigue. Wouldn’t it be easier to just name these ‘noble ideals’ we’re all supposed to aspire to specifically? Then there’s “to value and preserve the rich heritage of our composite culture”. What exactly is “our composite culture”? India has several cultures; is this some kind of strange Captain Planet reference? (With your powers combined, I am Composite Culture!) My favourite one is, “to strive towards excellence in all spheres of individual and collective activity so that the nation constantly rises to higher levels of endeavour and achievement”. Um… ok. Right. I’ll make sure I do that. Whatever that is. What it’s supposed to mean, I think, is do your best at whatever you’re doing. Which is what your mommy and daddy told you before sending you off to pre-school. Do we really need it in the Constitution?

So why have these seemingly superfluous provisions at all? Because today, more than ever before, we need to be reminded of a very basic and simple fact: that we need be good people. In a country racked by communalism, parochialism and violence against women, we need our nation-building document to tell us that we must “promote harmony and the spirit of common brotherhood amongst all the people of India transcending religious, linguistic and regional or sectional diversities” and “renounce practices derogatory to the dignity of women”. I especially like that last bit. Rather than using paternalistic phrases like “protect our mothers/daughters/sisters” or “modesty of women” (like we’re doing them a favour!), it tells us to introspect, evaluate our actions and renounce practices that hurt the dignity of women. In a country where we turn a blind eye to the worst mining practices, pollution on an industrial scale, indiscriminate poaching, and deforestation in the name of “development”, our Constitution tells us “to protect and improve the natural environment including forests, lakes, rivers and wild life, and to have compassion for living creatures”.

And in a country historically mired in superstition, ignorance, and blind religious bigotry, where even those who have had the advantage of a decent education believe that certain people are inferior by birth, that drinking untreated water from a polluted ‘holy river’, and eating the soil over which a ‘holy man’ has walked will cure a disease, we need our Constitution to remind us “to develop the scientific temper, humanism and the spirit of inquiry and reform”. Dr. Narendra Dabholkar was the champion of this fundamental duty, the pursuit of logical, rational thought in the face of unquestioning belief, before he was gunned down so ruthlessly in Pune. It’s ironic that the very next clause in the Article urges citizens to “abjure violence”.

And in a country historically mired in superstition, ignorance, and blind religious bigotry, where even those who have had the advantage of a decent education believe that certain people are inferior by birth, that drinking untreated water from a polluted ‘holy river’, and eating the soil over which a ‘holy man’ has walked will cure a disease, we need our Constitution to remind us “to develop the scientific temper, humanism and the spirit of inquiry and reform”. Dr. Narendra Dabholkar was the champion of this fundamental duty, the pursuit of logical, rational thought in the face of unquestioning belief, before he was gunned down so ruthlessly in Pune. It’s ironic that the very next clause in the Article urges citizens to “abjure violence”.

We are all quick to scream about our fundamental rights, and we definitely should – that’s the very basis of a robust democracy. But, as law students learn quite early on in their academic careers, every right has a corresponding duty. When criticised for promoting superstition and dangerous archaic beliefs, the accused tend to turn immediately to Articles 25 and 19. Well yes, they have the right to say what they want. I believe that the freedom of expression is a right that should not be touched, but that is predicated on the belief that every person has the intelligence to judge and evaluate what s/he is hearing, seeing, or reading and make a reasoned decision about it. It is also predicated on the idea that every person has a duty to respect the other’s freedom of expression and right to criticise. It works both ways.

Our Fundamental Duties, ambiguous and inconsequential as they may seem, are our Constitution’s hope for a better, more mature, more intelligent body of people. The Constitution is almost like a living, breathing being which is on a mission to make our lives better. It keeps giving and when it feels it is failing us, it changes and improves itself. It asks for little in return. And to our complete and unending shame, we let our Constitution down again and again, until it lies bleeding and lifeless in the form of a tireless worker for reform, rationalism, and progress while we watch and shake our fists with impotent rage and walk away.

(Sayak Dasgupta wanders around myLaw.net looking for things to do.)