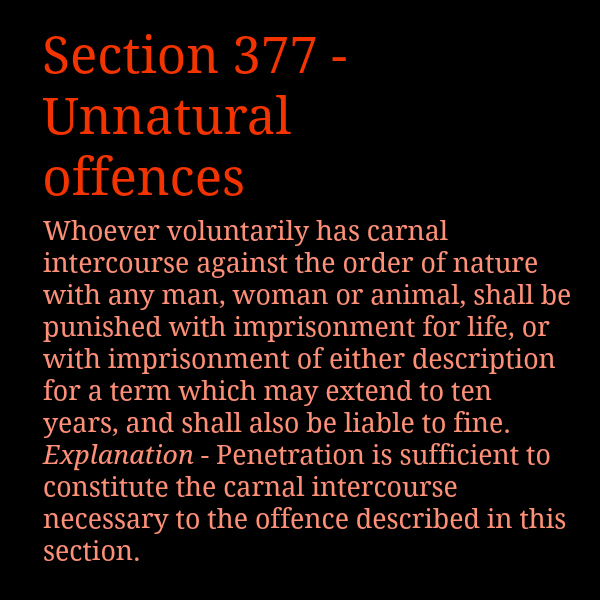

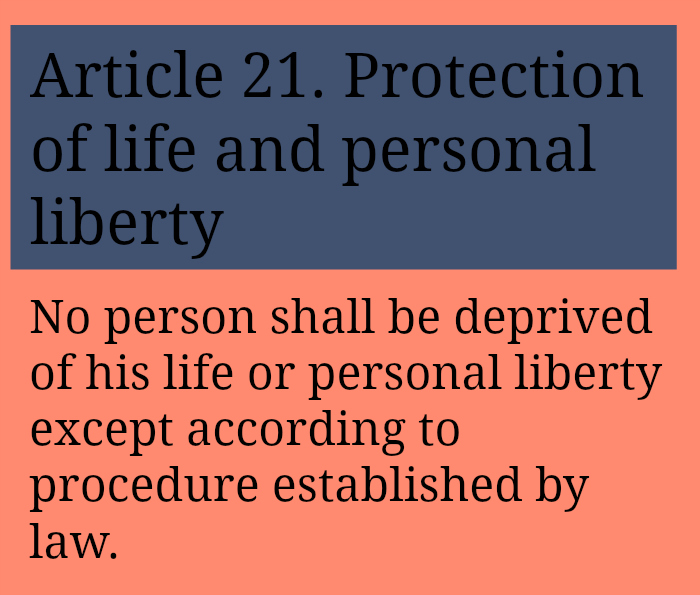

The Delhi High Court had concluded that interpreting Section 377 to include consensual acts between adults violated Article 21. The Court had reasoned that not doing so would result in:

The Delhi High Court had concluded that interpreting Section 377 to include consensual acts between adults violated Article 21. The Court had reasoned that not doing so would result in:

– Violation of the right to dignity, which is part of the right to life, as interpreted by the Supreme Court. The High Court provided a Kantian colour to the meaning of ‘dignity’, stating that “at root of the dignity is the autonomy of the private will and a person’s freedom of choice and of action”, and that “Section 377 IPC denies a person’s dignity and criminalises his or her core identity solely on account of his or her sexuality and thus violates Article 21 of the Constitution.”

– Violation of the right to privacy, which is part of the right to life, as interpreted by the Supreme Court, and internationally. The right to privacy thus has been held to protect a “private space in which man may become and remain himself”, and “privacy recognises that we all have a right to a sphere of private intimacy and autonomy which allows us to establish and nurture human relationships without interference from the outside community. The way in which one gives expression to one’s sexuality is at the core of this area of private intimacy.”

– Violation of the right to privacy, which is part of the right to life, as interpreted by the Supreme Court, and internationally. The right to privacy thus has been held to protect a “private space in which man may become and remain himself”, and “privacy recognises that we all have a right to a sphere of private intimacy and autonomy which allows us to establish and nurture human relationships without interference from the outside community. The way in which one gives expression to one’s sexuality is at the core of this area of private intimacy.”

– The law being unreasonable, as no compelling state interest was proved — this is a requirement under Article 21 as interpreted by the Supreme Court for validity of a law curtailing personal liberty. The high incidence of HIV/AIDS among male homosexuals and their medical treatment to ‘cure’ them of homosexuality were raised as arguments to show a compelling state interest in support of criminalisation. These arguments were rejected in the face of contrary evidence (from the National Aids Control Organisation and the Ministry of Health) that criminalisation actually increases health risks by driving affected individuals underground where they are susceptible to severe harassment, and psychological studies indicating that homosexuality is not a ‘disease’. ‘Reasonableness’ therefore, was not proved, especially as the State admitted that Section 377 was not enforced against homosexuals in practice, which betrayed the absence of a genuine public health interest. Popular morality against homosexuality, it was also argued, provided a compelling state interest in criminalising it. This argument was rejected as popular morality is distinct from constitutional morality, and only the latter can be used to restrict fundamental rights. Mere disapproval is not a sufficient reason for criminalising an activity.

Again, there were three distinct grounds (highlighted in bold above) in relation to life and personal liberty on the basis of which the High Court interpreted Section 377 to exclude carnal intercourse between consenting adults in private. In order to set aside the judgment of the High Court, it was necessary for the Supreme Court to conclude that each of these grounds was fallacious.

Analysis of the Supreme Court judgment in relation to life and personal liberty (Paragraphs 45 to 49 and 52 to 53)

In Paragraph 45, the judgment recognises that Article 21 requires laws to be just, fair, and reasonable. Paragraphs 46, 47, and 50 acknowledge that privacy and dignity are within the ambit of Article 21.

In Paragraph 48, a case is cited in the context of reproductive rights and abortion to demonstrate that while a woman has full control over her reproductive rights under Article 21, the right to abortion is not absolute. The conditions for abortion specified in the Medical Termination of Pregnancy Act, 1971 are reasonable given the “compelling state interest in protecting the life of the prospective child”. The judgment does not discuss how this case provides a sufficient analogy to establish a compelling state interest in criminalising consensual penile–non-vaginal intercourse.

In Paragraph 49, another case is cited in the context of the medical duty of confidentiality of patients. Recognising that although a patient has a general right of privacy, the duty of confidentiality does not prevent a doctor from informing the patient’s wife-to-be that he (the patient) is HIV+. Again, there is no discussion how this analogy is relevant in to consensual penile–non-vaginal intercourse.

Needless to say, in contrast to the examples in Paragraphs 48 and 49, the existence of consent and the absence of harm would be distinguishing factors.

Out of the three challenges under Article 21, the judgment only attempts to deal with ‘reasonableness’ and ‘existence of a compelling state interest’. The challenges under the right to privacy and the right to dignity are not refuted.

In Paragraphs 52 to 53, the judgment cites other cases to the effect that judgments from foreign jurisdictions need not necessarily be adopted by Indian courts. This is correct, The reliance on foreign judgments by the High Court however, was only to develop persuasive reasons within the framework of the requirements of the Indian Constitution, and not as an appeal to formal authority. Without addressing the arguments on privacy and dignity, disapproving the reliance on foreign judgments and using it to set aside the judgment of the High Court is a case of missing the forest for the trees.

There were six distinct constitutional challenges to the existing interpretation of Section 377 – three each under Articles 14 and 15 (which I wrote about in the first part of this article) on one hand, and Article 21 on the other. To set aside the judgment of the High Court, the Supreme Court had to refute each of these six challenges. To say it fell short of doing so in respect of any of them is an understatement.

Amidst signs of a possible political solution to negate the effect of the judgment, it is clearly not a stage where something like a ‘jail bharo’ campaign would appear to be a conscientious imperative to force a change in an unjust law. It would be ideal that the Supreme Court sets right this constitutional malady on its own in review or curative proceedings.

The next part of this article will look at the debate around the presumption of constitutionality of laws and judicial overreach.

(Aditya Verma practices as an Advocate at the Supreme Court of India. He is an alumnus of NLSIU, Bangalore, and is on the roll of solicitors in England and Wales.)