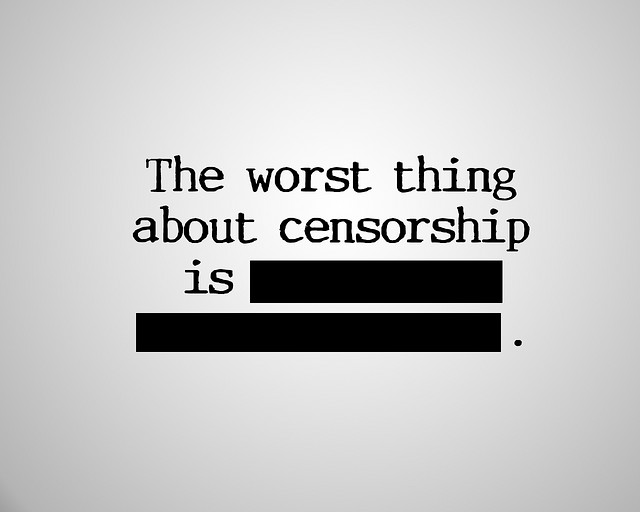

Disagreement on vital issues of constitutionality did not stop the passage of the Juvenile Justice (Care and Protection of Children) Bill, 2014 (“the Bill”) in the Lok Sabha. Apart from the floor of the Parliament, these issues were also raised in submissions to the Parliamentary Standing Committee and in the print and visual media.

Disagreement on vital issues of constitutionality did not stop the passage of the Juvenile Justice (Care and Protection of Children) Bill, 2014 (“the Bill”) in the Lok Sabha. Apart from the floor of the Parliament, these issues were also raised in submissions to the Parliamentary Standing Committee and in the print and visual media.

In a drastic and regressive move, the Bill proposes the introduction of a transfer system so that children aged between 16 and 18 years and alleged to have committed ‘heinous offences’ can now be tried and sentenced as adults.

The right to equality under Article 14 and the special protection for children under Article 15(3)

By treating adolescents as adults, the proposed system will incorrectly treat two distinct categories equally. This strikes at the very core of Article 14. The Supreme Court has repeatedly endorsed as part of the Article 14 mandate (See, M. Nagaraj v. Union of India, AIR 2007 SC 71 and Joginder Nath v. Union of India, AIR 1975 SC 511), the principle that injustice arises not only when equals are treated unequally, but also when unequals are treated equally.

This animation, comprised of MRI scans, shows changes in the brain between the ages of 5 and 20. Red indicates more grey matter and blue indicates less.

Advances in neuroscience show that adolescents are neurobiologically distinct from adults. Even though persons in this age group may ‘know what they are doing is wrong’, they have been shown incontrovertibly to be unable to act on that knowledge and restrain themselves. This is because they underestimate risk, are susceptible to negative influences, and lack foresight.

They are also more amenable to reform and rehabilitative interventions because of the plasticity of their brains. As stated in an amicus brief for the American Psychological Association, the American Psychiatric Association, and the National Association of Social Workers before the Supreme Court of the United States in Miller v. Alabama, juveniles “typically outgrow their antisocial behaviour as the impetuousness and recklessness of youth subside in adulthood”.

The special protection of 16 to 18 year olds, present in the current law and negated by the Bill, is saved by Article 15(3) of the Constitution, which permits special legal provisions for women and children because uniform laws cannot address the particular vulnerability of women and children. The transfer system militates against this goal as well as the overall objective of the Bill to ensure care, protection, and the ultimate rehabilitation of children in conflict with the law.

The constitutional prohibition on procedural arbitrariness under Articles 14 and 21

The Bill requires the Juvenile Justice Board to assess, along with the circumstances in which the heinous offence was allegedly committed, whether the child offender had the physical and mental capability to commit the offence. The latest research indicates that individualised assessments of adolescent mental capacity are not possible. Any suggestion that it can be done would mean “exceeding the limits of science”. (See, Bonnie & Scott, “The Teenage Brain: Adolescent Research and the Law”, Current Directions in Psychological Science, 22(2) 158–161 (2013), p.161.)

The assessment proposed in the Bill is fraught with errors and arbitrariness and will allow inherent biases to determine which child is transferred to an adult court. The assessment also violates the principle of presumption of innocence as it operates on the assumption that the child has committed the offence.

Procedural arbitrariness is inherent in the assessment of reformation by the Children’s Court

When a juvenile sentenced by the Children’s Court attains the age of 21 years, she or he will be subjected to another assessment to determine whether or not the person has reformed and can make contributions to society.

Already, half the children apprehended for offences come from families with an annual income of less than Rs. 25,000 while only 0.55% of the children apprehended come from families with an annual income of more than Rs. 3,00,000 (See, Crime in India, 2013, Compendium, National Crime Records Bureau (2014), pg 4.) Undoubtedly, the provisions of the Bill will result in class, caste and religion-based targeting of children under the garb of assessing their potential contribution to society and extent of reformation.

Protection against disqualification violates the right to life under Article 21 and the right to equality under Article 14

Maneka Gandhi (right), the Union Minister for Women and Child Development introduced the Bill in the Lok Sabha. Shashi Tharoor spoke about the problems with treating 16-18 year olds as adults.

Children between 16 and 18 years found to be in conflict with the law under Clause 20(1)(i) will incur disqualifications. While all children are protected against disqualification attached to conviction, the Bill deprives children convicted of heinous offences of this protection, thus discriminating among children based on the forum for trial, the offence, and the age.

They will therefore have to declare the conviction while applying for jobs or traveling abroad. The record of conviction will stigmatise them and make their rehabilitation and re-integration impossible.

The right to life entails the right to livelihood as well as a life of dignity. This stands compromised through the retention of the record of conviction and the withdrawal of protection from disqualification. This also means that a finding of ‘reformation’ and the ability to make a positive contribution to society based on another arbitrary assessment proposed under Clause 21 will be rendered meaningless, as the conviction will be held against the child for life.

The Department-Related Parliamentary Standing Committee on Human Resource Development also highlighted these constitutional concerns in its Two Hundred Sixty-Fourth Report. In para 3.21, it concluded that, “the existing juvenile system is not only reformative and rehabilitative in nature but also recognises the fact that 16-18 years is an extremely sensitive and critical age requiring greater protection. Hence, there is no need to subject them to different or adult judicial system as it will go against Articles 14 and 15(3) of the Constitution.”

Policy consensus based on evidence has to precede law making in a Parliamentary democracy. Examples from western countries that have experimented with the transfer system show that such a policy change will only result in higher costs related to incarceration and the deferred costs of the rage and bitterness that come from life in the adult criminal justice system.

Sending juveniles who allegedly commit ‘serious’ crimes to jail on the pretext of public safety is not in the interest of children, families, or the wider community. Placing adolescents who are at a difficult transitional phase in their lives along with adult criminals will only serve to place these young people at risk of being physically, sexually and emotionally abused and being further criminalised. This regressive outcome is in stark contrast to our constitutional mandate and the rehabilitative aims outlined even in the preamble of this Bill.

Swagata Raha, Arlene Manoharan, and Shruthi Ramakrishnan are from the Centre for Child and the Law, NLSIU Bangalore.