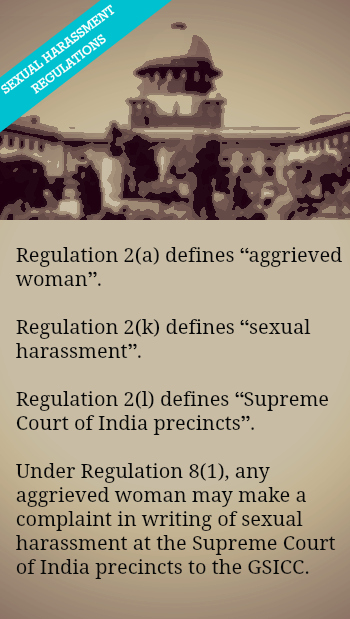

“No woman shall be subjected to sexual harassment at the Supreme Court of India precincts”, proclaims Regulation 3 of the Gender Sensitisation & Sexual Harassment of Women at the Supreme Court of India (Prevention, Prohibition and Redressal) Regulations, 2013 (“the Regulations”). The Supreme Court of India notified the Regulations in exercise of its administrative jurisdiction. They are now in force and apply independent of other laws that may apply, such as the yet-to-be-notified Sexual Harassment of Women at Workplace (Prevention, Prohibition, and Redressal) Act, 2013.

“No woman shall be subjected to sexual harassment at the Supreme Court of India precincts”, proclaims Regulation 3 of the Gender Sensitisation & Sexual Harassment of Women at the Supreme Court of India (Prevention, Prohibition and Redressal) Regulations, 2013 (“the Regulations”). The Supreme Court of India notified the Regulations in exercise of its administrative jurisdiction. They are now in force and apply independent of other laws that may apply, such as the yet-to-be-notified Sexual Harassment of Women at Workplace (Prevention, Prohibition, and Redressal) Act, 2013.

The Regulations apply to everyone, not just lawyers (although the definition of aggrieved woman does not include “any female who is already governed by the Supreme Court service regulations”). They are significant because they acknowledge that the sexual harassment of women in the professional environment of litigation is a real problem, especially because litigation has traditionally been a heavily male-dominated profession. But do the Regulations go far enough?

The Regulations apply to everyone, not just lawyers (although the definition of aggrieved woman does not include “any female who is already governed by the Supreme Court service regulations”). They are significant because they acknowledge that the sexual harassment of women in the professional environment of litigation is a real problem, especially because litigation has traditionally been a heavily male-dominated profession. But do the Regulations go far enough?

The GSICC

A ten-member Gender Sensitisation and Internal Complaints Committee (“the GSICC”), headed by Justice Ranjana Prakash Desai, has been constituted under the Regulations. The GSICC (through an Internal Sub-Committee of three members constituted in relation to any particular complaint) inquires into complaints of sexual harassment. Such inquiries must be completed within ninety days.

Upon completion of the inquiry, if the complaint is found to be genuine, the GSICC has the power to admonish and also publish such admonition. It can also take other necessary steps to prevent or prohibit future harassment by placing appropriate restrictions on contact between the complainant and the respondent.

Upon completion of the inquiry, if the complaint is found to be genuine, the GSICC has the power to admonish and also publish such admonition. It can also take other necessary steps to prevent or prohibit future harassment by placing appropriate restrictions on contact between the complainant and the respondent.

Crucially, for deterrence, the GSICC can recommend to the Chief Justice of India, that other orders be passed against the respondent, including orders to debar the respondent’s entry into the Supreme Court precincts up to a maximum of one year. It can also recommend the filing of a criminal complaint and a complaint to a disciplinary authority (such as a bar council). A person aggrieved by an order passed (or not passed) by the GSICC can make a representation to the Chief Justice of India to have it set aside or modified.

Simple and flexible procedure

The standard of proof required for the inquiry procedure is not expressly specified. The inquiry however, has the trappings of civil proceedings with purely civil consequences, which indicates that the normal standard of proof in civil cases would be applicable, that is, the preponderance of probabilities.

The standard of proof required for the inquiry procedure is not expressly specified. The inquiry however, has the trappings of civil proceedings with purely civil consequences, which indicates that the normal standard of proof in civil cases would be applicable, that is, the preponderance of probabilities.

The Regulations provide for a relatively simple and flexible procedure for the GSICC and the Internal Sub-Committee. It is appropriate that the GSICC will always be headed by a judge of the Supreme Court as that can ensure consistent adherence to the principles of natural justice and fair play. There may often be an imbalance of power between the complainant and the respondent, which makes it doubly important that the procedure is kept uncomplicated.

While a forensic examination of the Regulations will have to be more detailed, a couple of aspects that may scupper the efficacy of the Regulations in the long term are highlighted below.

Applicability of the Regulations is restricted to the ‘Supreme Court of India precincts’

This is narrower than the concept of ‘workplace’ contemplated under the Sexual Harassment of Women at Workplace (Prevention, Prohibition, and Redressal) Act, 2013 (and also under the guidelines laid down in Vishaka v. State of Rajasthan. “Workplace” need not be restricted by a brick-and-mortar interpretation, given that sexual harassment has more to do with the relationship and power dynamic between people than the physical space they occupy.

A more considered approach may have to be taken to identify those categories of persons whose relationship with each other has a relevant nexus with the Supreme Court as a workplace, in order that it is appropriate for the administrative jurisdiction of the Supreme Court to extend to their conduct beyond its precincts. An allegation by an intern against a judge of sexual harassment in a hotel room, as a case in point, may well fall outside the purview of the Regulations altogether (See for reference, the amicus petition submitted by Lawyers’ Collective).

Definition of sexual harassment and the scope of the inquiry

In what may be an inadvertent oversight, if a literal interpretation is given to Regulations 2(k)(x) – 2(k)(xiii), the following acts may amount to sexual harassment under the Regulations even if they are no t sexually motivated in any manner:

t sexually motivated in any manner:

– ‘implied or explicit promise of preferential treatment in her legal career’

– ‘implied or explicit threat of detrimental treatment in her legal career’

– ‘implied or explicit threat about her present or future legal career’

– ‘interference [sic] with her work or creating an intimidating or offensive or hostile work environment for her’

Of course, such acts, if sexually motivated, should fall within the definition of sexual harassment. However, the definition as it currently stands does not require them to be so motivated.

Further, the interpretation of the Regulations vis-à-vis the definition of sexual harassment and the scope of enquiry by the GSICC may also pose problems. For example, sexual harassment can occur via text and electronic messages (Regulation 2(k)(v)). It is difficult to reconcile this with an inquiry whose scope is restricted to sexual harassment ‘at the Supreme Court of India precincts’. It would be impractical to seek proof that such text or electronic messages were either sent from or seen within a particular physical space. Regulation 2(k)(vi) includes ‘stalking or consistently following aggrieved woman in the Supreme Court precincts and outside’, which appears to be incongruous with the geographical limitation otherwise placed on the scope of the complaint or inquiry.

Finally, there may be a day when laws and regulations against sexual harassment will be gender-neutral in all respects.

(Aditya Verma practices as an Advocate at the Supreme Court of India. He is an alumnus of NLSIU, Bangalore, and is on the roll of solicitors in England and Wales.)