Sarita tai was worried about the construction of a railway line between the iron ore mine and the railhead located 30 kilometres from the village she worked at. At least 15 kilometres of this railway line would cut through an important part of the central forest belt. She called me with many questions: What was the process for taking permissions for using forestland for railway lines? Had this process been completed? What was the role of the gram sabha? What if the forest rights of people had not been fully recognised yet?

Sarita tai was worried about the construction of a railway line between the iron ore mine and the railhead located 30 kilometres from the village she worked at. At least 15 kilometres of this railway line would cut through an important part of the central forest belt. She called me with many questions: What was the process for taking permissions for using forestland for railway lines? Had this process been completed? What was the role of the gram sabha? What if the forest rights of people had not been fully recognised yet?

Some of these answers came easy but the others required the study of some recent circulars and directions of the environment ministry, the tribal affairs ministry, and the National Green Tribunal (“NGT”).

EIAs for railway lines

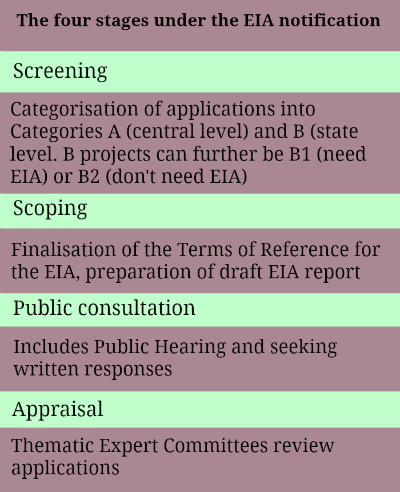

Surprising as it may seem, the railway line and its related infrastructure are not in the list of projects that need to go through the procedure laid out in the EIA Notification, 2006 issued under the Environment Protection Act, 1986. We have long tried to find the logic behind it, but without success. Railway projects simply do not require an environment impact assessment and a public consultation for an environmental clearance.

If the railway line is separated from the other components of the project like it was in the case of the mine that Sarita tai was worried about, it could easily avoid the environment impact assessment process. The mine had been up and running for the last year and the proposal for the railway line was only mooted much after the environment clearance was procured for the mine.

Forest diversion and the felling of trees

All non-forest use requires the user agency to seek prior approval under the Forest Conservation Act, 1980. There is a detailed procedure under Section 2, which remains away from public eye and only within negotiations between forest department officials; the Ministry of Environment, Forests and Climate Change (“MoEFCC”); and the user agency.

Until recently, no activity related to a project could be carried out for any non-forest use until the entire procedure, which includes a two-stage approval by the MoEFCC and an order by the government of the state where the forest is located, was completed. Felling trees would be illegal without it.

But during the last year, the MoEFCC has allowed the felling of trees to be carried out after a project receives “Stage 1 approval”, that is, the approval of the MoEFCC. This approval often contains conditions including additional studies related to hydrology, impact on wildlife, identification of compensatory afforestation land and others that have a bearing on whether the forest diversion should be approved or not. But in the case of linear projects such as railways, highways or transmission lines, the MoEFCC has attempted to be create a “simplified procedure.”

In a set of guidelines issued on May 7, 2015 and subsequently updated on August 28, 2015, the ministry said that to allow for the speedy execution of these projects, the in-principle approval will be enough to allow for both tree cutting and commencement of work if all “compensatory levies” and a wildlife conservation plan are ready.

Sarita tai was livid. The last time she had seen an in-principle approval, it listed 27 important conditions including that of redoing some important assessments. What is the point going through the remaining procedure for this project if the work can commence and trees can be cut, she asked. It defeats the entire purpose of any safeguards or conditions levied.

I agreed and told her that these guidelines had been challenged before the NGT. In January 2015, the NGT first restrained the felling of trees after Stage 1 approval, but subsequently reviewed the order in the light of an affidavit submitted by the MoEFCC. In its direction, the NGT concluded that the while tree felling and commencement of work might be allowed for linear projects it would be treated as an order under Section 2 of the FCA and therefore can be challenged before the NGT. This is important to understand because the NGT had previously ordered that only those orders issued finally by state governments activating forest diversions could be brought before it. Till then no commencement of work or tree felling could be allowed.

I agreed and told her that these guidelines had been challenged before the NGT. In January 2015, the NGT first restrained the felling of trees after Stage 1 approval, but subsequently reviewed the order in the light of an affidavit submitted by the MoEFCC. In its direction, the NGT concluded that the while tree felling and commencement of work might be allowed for linear projects it would be treated as an order under Section 2 of the FCA and therefore can be challenged before the NGT. This is important to understand because the NGT had previously ordered that only those orders issued finally by state governments activating forest diversions could be brought before it. Till then no commencement of work or tree felling could be allowed.

The MoEF’s May 7 and August 28, 2015 guidelines lay down that while the “simplified” procedure for the speedy execution of linear projects remains in place an “aggrieved person” now has the option to approach the NGT with an appeal against this order.

Forest rights and linear projects

I knew that Sarita tai would also ask about the recognition of the rights of forest dwelling communities who have historically either lived or used the forest that is sought to be diverted. The Scheduled Tribes And Other Traditional Forest Dwellers (Recognition Of Forest Rights) Act, 2006 mandates the recognition of individual and community forest rights of tribal and other forest dwelling communities.

On August 3, 2009, the MoEFCC issued an important circular, which, among other things, clarified that no diversion of forest land for non-forest use would take effect unless the process of recognition of rights had been completed. It also said that the consent of the gram sabhas would be required before the diversion process can be given effect. This has also been re-iterated and confirmed by the Ministry of Tribal Affairs (“MoTA”), which oversees the implementation of the FRA.

In the villages that Savita tai was working in, several of the community forest rights claims were still pending final approval and the grant of individual rights had been contentious as people had only received rights over a part of the forest land that had been claimed. In their view, their rights over the forests were yet to be recognised. So the first question that came to our mind was whether the forest diversion and tree cutting could have come into affect if the recognition of rights was pending. The gram sabha (village assembly) had confirmed that their consent had not been sought.

This issue had been a bone of contention between the MoTA and the MoEFCC since 2013. While the MoEFCC had claimed through their February 5, 2013 circular that the requirement of the gram sabha consent could be dispensed for linear projects, the MoTA, the nodal ministry, said that the MoEFCC had no authority to make such an interpretation. All projects, linear or non-linear, had to be treated equally regarding forest diversions and consent provisions.

These different interpretations continue to operate and the MoEFCC has been approving proposals for forest diversion and allowing for tree felling for linear projects, interpreting that a gram sabha nod was not required, especially in cases where there has been an assurance from the state government that either the rights under FRA have been recognised or are in the process of being so.

A worrying scenario

Thus, with no requirement of EIAs once a railway line is segregated from other aspects of a project; tree felling permitted after in-principle approvals; and tentative interpretations for gram sabha consent; the situation did not seem very encouraging to Sarita tai and the affected people that she was working with. They could however, still petition the concerned ministries. No doubt, the fate of the project and the forest dependent people could still lie in bureaucratic interpretations and the application of mind by expert committees.

With no court action on the anvil immediately and the affected communities clearly aligned to question both the FCA guidelines and the dilution of the consent provisions; its anyone’s guess whether the railway line will be built or not. But it once again raises questions about why any project, which has a far-reaching impact on forests, wildlife, and people, should be granted exemptions from basic environmental scrutiny and stringent safeguards. Meanwhile, people like Sarita tai have to grapple with many interpretations of the law on a case-by-case basis.

Kanchi Kohli is a researcher working on law, environment justice, and community empowerment.