It was a hot summer afternoon in central India. Four of us had spent all morning taking a close look at an underground coalmine, its housing colonies, roads, transportation area, and other support infrastructure. We stopped to chat with workers at a local teashop. Even though we were fascinated and moved by their stories, we had to move on.

It was a hot summer afternoon in central India. Four of us had spent all morning taking a close look at an underground coalmine, its housing colonies, roads, transportation area, and other support infrastructure. We stopped to chat with workers at a local teashop. Even though we were fascinated and moved by their stories, we had to move on.

We had come to this place to understand how an important river had been polluted and the impact of this pollution. For many villages, this river and its feeder streams were important sources of water for drinking and for irrigation.

Across the road from the boundary wall of the mine, visible under a muddy patch of the road where we stood, was the mouth of a metal pipe. It was discharging thick black slurry. The slurry was heading straight into a stream flowing along the road. It was difficult to ascertain the source of the slurry in the pipe. Instead of following the pipe, we decided to follow the slurry.

After walking along the stream till it was not possible to trek any further, we met a resident of the area. “This polluted stream meets our river”, he said. “We are not able to use water from the river confidently any more. We are not even sure if it is fit for cattle. We have no clue what the black slurry is bringing with it.”

It was true. When we drove down towards the main river, we saw that it had been contaminated. There was no way to tell whether the water was poisonous or not. But it was clear that the discharge from the pipeline had been collecting on the river bed and blocking the easy flow of the river. Other residents of the area told us that the water flow is much stronger on some days.

To me, the veracity of their apprehension was just as big a question as whether the discharge should have been allowed in the first place. Since no one really knew who was responsible for constructing the pipeline and getting away with the effluent discharge, we had to understand the possible legal options for two scenarios – one where we knew who was responsible for the effluent discharge and one where that was not the case.

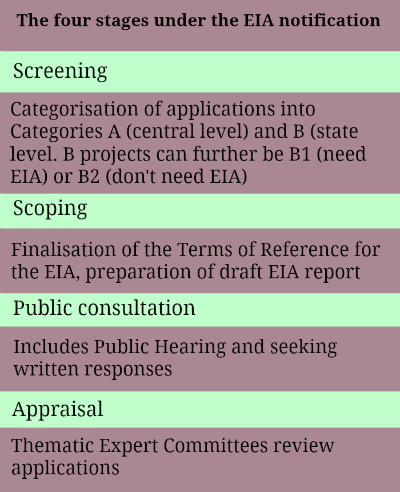

Almost all industries, mines and infrastructure activities where there is possibility of water extraction or water contamination are regulated at least by two laws: the Environment Protection Act, 1986 (“EPA”) and the Water (Prevention and Control of Pollution) Act, 1974 (“Water Act”). These industrial activities or processes would have also had to take approval under the Environment Impact Assessment Notification, 2006 (“EIA notification”) and seek consent under the Water Act.

When the source of pollution is known

If formal or informal sources indicated that the underground mine was indeed the source of the pollution, the course of action would be to immediately collect copies of the permissions granted under the EIA notification and the consent to operate letter from the relevant pollution control board.

Both the EIA-related permission (“environment clearance”) and the “consent to operate” are likely to have conditions related to how the polluted water to should be treated and where it should be discharged.

For instance, an environment clearance letter would say: “Mine water discharge and/or any wastewater should be properly treated to conform to the prescribed standards before reuse/discharge”. If this was mentioned in the approval given to the underground mine, then the discharge of the slurry into the stream would constitute a legal violation.

Sections 25 and 26 of the Water Act would also specifically be applicable to the underground mine. The project owners would have had to seek an approval from the Pollution Control Board clearly indicating the quantum and place of discharge. In their “consent to operate” letter, it is likely that the Pollution Control Board would have mentioned that coal waste should not be released into the neighbouring stream.

Environment clearance is a one-time permission given either by the Ministry of Environment, Forests and Climate Change or a state environment impact assessment authority. On the other hand, the consent to operate needs to be renewed every year by the relevant pollution control board, in charge of checking water pollution. For industries, the validity of the approval is five years to initiate the operations. No renewals are required thereafter. It is these pollution control boards or their regional offices, which also monitor whether these conditions are being followed.

When the source of pollution is not known

“But, there is no way we can find out the source of the pipeline. Only the discharge point is visible to us. However, we know that every 10-12 days, the discharge is much heavier than other days and the river is dark. Is there anyone we can complain to about this? , a teenaged schoolgirl, who had been overhearing our conversation, asked.

The Water Act has a clear objective of “prevention and control of water pollution and the maintaining or restoring of wholesomeness of water”. Pollution control boards (“PCBs”) set up under this law, have the responsibility for ensuring this. In fact, since 1974, these PCBs have been empowered by Section 17 (a) of the law to “to plan a comprehensive programme for the prevention, control or abatement of pollution of streams and wells”

Section 24 of the Water Act relates to prohibition of the use of a stream or a well for the disposal of polluting matter, by anyone. It did not really matter therefore, if we did not know the source of pollution. The PCB or its regional office could be asked to take action. People could meet the relevant officials or, as environmental groups or people with the help of civil society organisations have often done, file a written complaint.

Not surprisingly, my explanation was dismissed by a few in the group. “Why should we take the headache of going through all this paperwork when it is the responsibility of the government”, said one of them who seemed to be visiting his village from the neighbouring town. “No one cares about our place, or river”, another remarked.

I did not have any strong reason to disagree with the second remark. It is true that many regulatory procedures related to the environment are yet to be implemented to their true potential. Close to forty years of water pollution law in India and our rivers are still being polluted.

But I responded to the former remark. There is much to be desired from our regulatory institutions and they hide behind the excuses of lack of personnel and “pressures” leading to inaction. The filing of complaints before them however, remains an option for those who are affected. By not filing any complaints, are we not accepting the inaction? Perhaps an increase in evidence-based complaints can push the institutions to respond?

The extent to which affected people are willing to take their chances is a big question.

Kanchi Kohli is a researcher working on law, environment justice, and community empowerment.