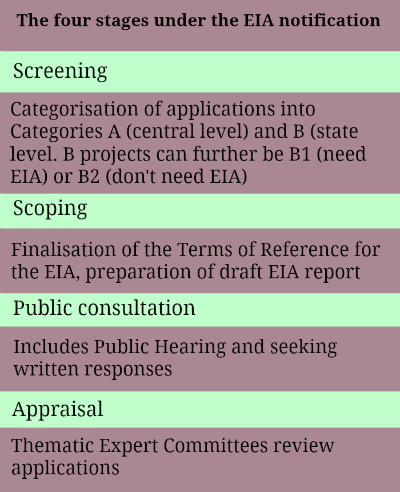

While many statutes are brought into existence through legislative processes, some, such as notifications, come about through executive action that does not require legislative approval. Notifications are designed to issued and later modified and clarified through executive action alone, with public input or without. One significant notification lays out the procedure for what is popularly known as “environment clearance”. This is the Environment Impact Assessment Notification, 2006 (“the EIA notification”), which has for long been in the eye of storm in the discussions around “balancing” environment and development.

While many statutes are brought into existence through legislative processes, some, such as notifications, come about through executive action that does not require legislative approval. Notifications are designed to issued and later modified and clarified through executive action alone, with public input or without. One significant notification lays out the procedure for what is popularly known as “environment clearance”. This is the Environment Impact Assessment Notification, 2006 (“the EIA notification”), which has for long been in the eye of storm in the discussions around “balancing” environment and development.

Soon after the new government took office in May 2014, it announced a series of changes to the environment and forest regulations, some of which had already been rolled out during the previous regime. Since June 2014, there have been a quick series of draft amendments, internal ministerial notes, circulars, and office memoranda bringing in important changes to the EIA notification.

Legal basis of the EIA notification

The government of India first issued this notification in 1994, exercising its power under Sections 3(1) and 3(2)(v) of The Environment (Protection) Act, 1986 (“EPA”). The latter provision gives powers to the central government to place “restriction of areas in which any industries, operations or processes or class of industries, operations or processes shall not be carried out or shall be carried out subject to certain safeguards.”

Previously in this series of posts on Communities and Legal Action, I have dealt with public hearings and the steps that an affected community can take once an approval is granted for a project. Now, let us take a close look at the changes that have been made to the EIA notification and those that have been proposed. These will have a bearing on the applicability of this important piece of the regulatory structure.

They include the delegation of powers to state governments to make decisions, the creation of exceptions for project approvals, procedural relaxations, and adding new projects to the list of projects that require approval. All the circulars and changes described in this post are available here.

Projects that requiring environmental clearance – additions and clarifications

Some projects, such as coal tar projects, will now need to go through an “environment clearance” process, from which they had previously been exempt. Irrigation projects with a command area between 2000 and 10000 hectares will now need approval from the State Environment Impact Assessment Agency (“SEIAA”) and all irrigation projects above 10000 hectares will require approval from the Ministry of Environment, Forests, and Climate Change (“MoEFCC”), that is under Category A. Clearly, this means that all irrigation projects of capacity up to 2000 hectares of culturable command area are now exempt from an environmental clearance process, including any public consultation. River valley projects between 25 and 50 MW and with a command are between 2000 and 10000 hectares will now be appraised by the MoEFCC if the project falls in more then two states. It would have otherwise been the SEIAA’s responsibility.

Exemptions from any environmental clearance process or public consultation

A significant area of focus of the changes has been to exempt some types of projects from any environmental clearance and this has implications on sectors such as irrigation projects and coal mining projects. Coal mining projects that require a one-time capacity expansion with the production capacity exceeding 16 MTPA have for example been exempted from any public consultation (Office Memorandum dated July 28, 2014). After clarification (Office Memorandum dated September 2, 2014) was issued, this exemption will now apply to coal mining projects with production capacity exceeding 20 MTPA, provided the ceiling of the expansion is towards mining for an additional production up to 6 MTPA and if the transportation of coal proposed is by means of a conveyor or rails. However in both these instances, the Expert Appraisal Committee has to apply “due diligence” and it needs to be subject to “satisfactory compliance with environmental clearance(s) issued in the past as judged by the EAC.”

Restricting powers for appraisal at scoping stage

An Office Memorandum dated October 7, 2014 restricting the powers of appraisal at the scoping stage is also crucial. It indicates that the Expert Appraisal Committees (“EACs”) while reviewing the applications for environment clearance should only ask comprehensive sets of questions and studies at the time of issuing Terms of Reference for an EIA report to the project authority. The EACs review all documents related to the project including impact assessment submissions, videos recorded during the public consultation phase, and project reports and have to either recommend or reject approvals. They can ask project authorities to clarify issues, respond to queries raised at the public hearings, as well as carry out additional assessments.

An Office Memorandum dated October 7, 2014 restricting the powers of appraisal at the scoping stage is also crucial. It indicates that the Expert Appraisal Committees (“EACs”) while reviewing the applications for environment clearance should only ask comprehensive sets of questions and studies at the time of issuing Terms of Reference for an EIA report to the project authority. The EACs review all documents related to the project including impact assessment submissions, videos recorded during the public consultation phase, and project reports and have to either recommend or reject approvals. They can ask project authorities to clarify issues, respond to queries raised at the public hearings, as well as carry out additional assessments.

With this clarification however, additional studies, especially “fresh issues”, need to be added at the appraisal stage only if the EAC can clearly justify that these are inevitable and why they need to added at a later stage. These have to be stated unambiguously in the minutes. The purpose of this to address the complaints of project authorities that too many questions at the appraisal stage are causing delays. The very purpose of public scrutiny however, is to seek essential feedback to and address impact issues. Curtailing the powers of appraisal committees goes completely against the spirit of appraisal, which requires the EACs to do a “detailed scrutiny”.

Delegation to State Environment Impact Assessment Authority

More projects have come within the jurisdiction of the SEIAA, that is, approvals at the state level. These include all biomass-based thermal power projects and synthetic organic chemicals industries if located outside a notified industrial area or estate, with specific caveats.

The most important manner which this delegation has happened however, is by limiting the applicability of the General Condition of the EIA notification. With this change, only those Category B projects (to be approved at state level ordinarily) located within five kilometres of a national park, sanctuary, critically polluted area, ecologically sensitive area or an inter-state boundary would need to approved by MoEFCC. Prior to the amendment, this was 10 kilometres. So now, if a thermal power plant is coming up within 8 kilometres of a national park, it will only need to be appraised at the state level.

Other changes proposed to the EIA notification – linear projects, non-irrigation projects, and building and construction

Many more changes are proposed to the EIA notification but in these cases, public opinion has been sought on whether such amendments should be introduced. On September 30, 2014, a draft notification was issued proposing some critical changes, including doing away with public consultations for “all linear projects such as Highways, pipelines, etc., in border States.” It is not clear whether this includes inter-state borders.

The draft notification also proposed the addition of non-irrigation projects such as drinking water supply projects to the purview of the EIA notification. These projects do not require environment clearance at this point of time. Projects less than 5000 hectares of submergence area have been proposed as Category B projects. Projects equal to and greater than 5000 hectares submergence area would need to be considered as Category A under the July 25, 2014 notification.

Under a September 11, 2014 draft notification, building and construction projects which cover an area greater than or equal to 20000 square metres and having a built-up area greater than1, 50,000 square metres of built-up area need approval from the SEIAA. The same goes for townships and area development projects covering an area greater than or equal to 50 hectares and or having a built-up area of greater than or equal to 1,50,000 square metres. No other building or township projects need to get environment clearance.

Catching up with the notification

The EIA notification now has to be read in line with all the clarifications and amendments, which are routinely put forward MoEFCC. It is far from easy to read the notification along with all the “ifs” and “buts” which play up when it needs to be ascertained whether an act is legal under the notification. Unraveling all of it can leave many people gasping. For affected communities, this legalese still remains distant, even as they engage with this process, counting on the hooks within the law and the support groups standing besides them and pointing their attention to it.

Kanchi Kohli (kanchikohli@gmail.com) is an independent researcher and writer.