2014 promises to be a year of transformation for the Supreme Court of India. Far-reaching changes are expected on fundamental issues such as the appointment of judges and the reform of the procedure of the Court. The Gender Sensitisation and Internal Complaints Committee (“GSICC”) is also functional. How effective will it be in tackling sexual harassment at the highest court? Ten sitting judges will retire during the year. What impact will this have on lawyers and litigants?

2014 promises to be a year of transformation for the Supreme Court of India. Far-reaching changes are expected on fundamental issues such as the appointment of judges and the reform of the procedure of the Court. The Gender Sensitisation and Internal Complaints Committee (“GSICC”) is also functional. How effective will it be in tackling sexual harassment at the highest court? Ten sitting judges will retire during the year. What impact will this have on lawyers and litigants?

These themes are expected to dominate discussion about the Supreme Court in 2014.

Appointment of judges

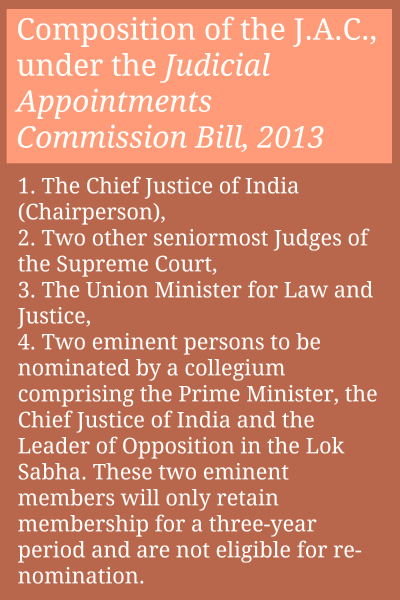

Political parties appear to be unanimous in their dissatisfaction with the current ‘collegium’ system, in which judges are appointed by senior judges of the Supreme Court. The proposed Judicial Appointments Commission (“JAC”) will take views from outside the judiciary into account. The outcome of the upcoming general elections is unlikely to affect the broad political support for the proposal.

Political parties appear to be unanimous in their dissatisfaction with the current ‘collegium’ system, in which judges are appointed by senior judges of the Supreme Court. The proposed Judicial Appointments Commission (“JAC”) will take views from outside the judiciary into account. The outcome of the upcoming general elections is unlikely to affect the broad political support for the proposal.

In a welcome move, the Parliamentary Standing Committee recommended the inclusion the JAC’s composition in the Constitution through an amendment, instead of it being part of a legislation. This reduces the possibility of a parliamentary majority exercising excessive control over the composition of the judiciary. This recommendation has been accepted by the government.

Of course, the standards applied for the selection of judges will be critical in assessing whether the JAC performs better than the collegium. Currently, the only standard stipulated is the ambiguous requirement that the person recommended should be “of ability, integrity and standing in the legal profession”.

Procedural reform

The E-committee of the Supreme Court, headed by Justice Madan Lokur, has initiated a number of steps to rationalise the process of filing and documentation at the Supreme Court. Highlights disclosed at a seminar at the Indian Law Institute late in 2013 include the electronic archiving of documents related to past and current litigation, a court-linked email address for each Advocate-on-Record for official communication with the Registry, and electronic filing of pleadings (‘curing defects’ may be done electronically – goodbye, white correction fluid!). Watch this space for updates on when these changes are formally notified.

Gender Sensitisation and Internal Complaints Committee

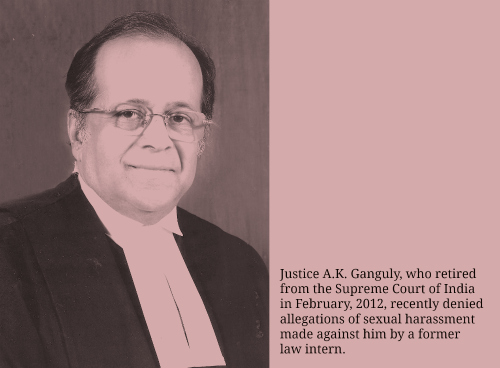

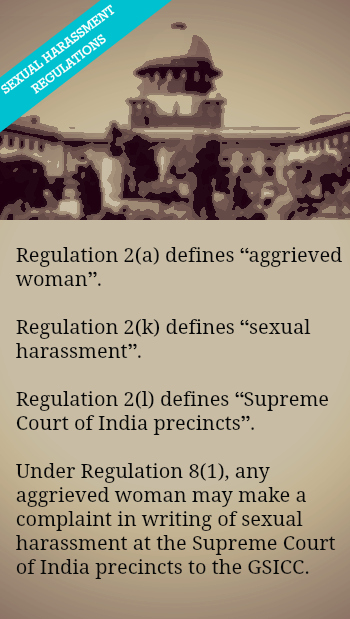

The GSICC was created last year, and has since been chaired by Justice Ranjana Prakash Desai. Part of its mandate is to address complaints of sexual harassment within the “Supreme Court of India precincts”. An internal sub-committee of three members has also been set up, comprising Ms. Indu Malhotra (Senior Advocate), Mr. L. Nageshwar Rao (Senior Advocate), and Ms. Bharti Ali (Co-director, HAQ: Centre for Child Rights).

According to the Annual Report of the GSICC, proceedings are underway in two complaints. Plans are also being made for sensitisation and publicity exercises. The next few months will provide a clearer indication of the GSICC’s efficacy, and whether the parent regulations need strengthening.

Retiring judges and new appointments

Ten (out of a maximum capacity of thirty-one) sitting judges are due to retire in 2014, and the office the Chief Justice of India will change hands twice during the year. The date of retirement acts as a kind of deadline for judges — they must deliver any pending judgments by that date. In view of the impending multiple retirements, it is possible that there will be a greater than usual output of judicial opinions in decided cases over the course of the year. New appointments will also be followed with interest, especially if the JAC starts functioning during the year.

And a tip of the hat

Delivering judgments is the most important function of the Supreme Court. No discussion today would be complete without a tip of the hat for the January 21, 2014 judgment in Shatrughan Chauhan and Another v. Union of India and Others, where unreasonable delay in the execution of a death sentence has been held to be in violation of Article 21, and a ground for commutation of the sentence. Apart from the direct impact the judgment has had on the cases of the fifteen writ petitioners before it and on death penalty jurisprudence in particular, the general observation of the Supreme Court that “retribution has no Constitutional value” in India deserves to be applauded wholeheartedly. “Punishment is not payback” should be a value that resonates throughout the criminal justice system.

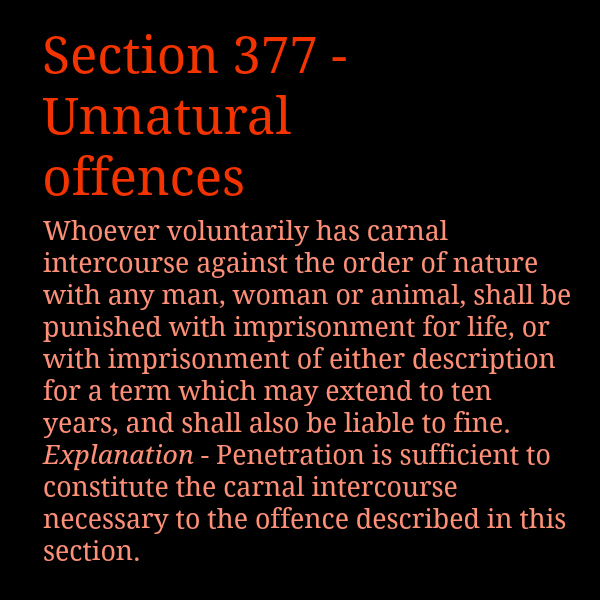

P.S. Last week, review petitions were dismissed without an oral hearing against the December 11, 2013 judgement in Suresh Kumar Koushal and Another v. NAZ Foundation and Others (analysed previously on this blog here, here, and here). Will Parliament set this right?

(Aditya Verma practices as an Advocate at the Supreme Court of India. He is an alumnus of NLSIU, Bangalore, and is on the roll of solicitors in England and Wales.)