The recent legal prosecution of AIB, a stand-up comics collective, has thrown open the debate on obscenity standards. In its show, AIB used cuss words and made express sexual innuendos. It was plainly visible that they were challenging, even if unwittingly, not only the conventional social mores but also the thresholds of obscenity law. Many see their prosecution as unfair and unequitable and evidence of greater intolerance in Indian society. Many have also questioned the law that formed the basis for the prosecution. It has been described as vague, indeterminate, and providing a ground for complaint to the least tolerant.

The recent legal prosecution of AIB, a stand-up comics collective, has thrown open the debate on obscenity standards. In its show, AIB used cuss words and made express sexual innuendos. It was plainly visible that they were challenging, even if unwittingly, not only the conventional social mores but also the thresholds of obscenity law. Many see their prosecution as unfair and unequitable and evidence of greater intolerance in Indian society. Many have also questioned the law that formed the basis for the prosecution. It has been described as vague, indeterminate, and providing a ground for complaint to the least tolerant.

This is properly a debate on the legal standards used to determine obscenity. As opposed to a debate on the necessity of the offence of obscenity itself. This article focusses on examining arguments for greater certainty in the legal tests for determining obscenity and seeks to build towards a more ambitious proposal, that legal tests and criteria cannot define obscenity to any reasonable certainty. Its moral desirability, even in the face of such subjectivity, is of course a choice left for the legislature.

The Hicklin test

The legal standards governing obscenity arise from the case of Ranjit Udeshi v. State of Maharashtra where the Supreme Court of India interpreted Section 292 of the Indian Penal Code, 1860. Though Section 292 only criminalises printed materials, its definition of obscenity is utilised in other criminal provisions such as Section 294, which criminalises obscene speech and songs. In Ranjit Udeshi, a five-judge bench of the Supreme Court of India adopted the Hicklin Test laid down in the case of Regina v. Hicklin by Justice Cockburn.

The test relies on gauging the content with respect to its tendency to deprave or corrupt. This depravity is reasoned to result from the content evoking or opening a person’s mind to any eroticism or sexual arousal. Finally, the test is not gauged from the perspective of an adult, but those minds which are open to such “immoral” influences. In a sense, its objective remains the infantilising of an adult mind. Our Supreme Court, while adopting this test, made slight modifications indicating that, “community standards” have an important bearing in adjudicating the legality of content as well. The case acknowledged that such obscenity can be part of a longer movie or song, but it had to, “remain in the shadows”. It is not without reason that old Bollywood movies contain visual innuendos, of a shaking bush or a rocking bed to represent love making.

The test by itself, on its very face, seems vague and incomprehensible and this seemed to be within the contemplation of the judges as well. They wrote in the decision itself that the “court must, therefore, apply itself to consider each work at a time.” In a sense, this revolts against the necessity of giving adequate notice to authors and artists.

This subjectivity became visible when the Supreme Court, in the case of C.K. Kakodar v. State of Maharashtra, applied the Hicklin Test. To gauge the obscenity in a story, it examined the theme of the story, the main protagonists, and the “artistic merit” in it. Explaining its approach, the Court stated that its duty was to “ascertain whether the book or story or any passage or passages offend the provisions of S. 292”. This implicitly recognises that it requires highly trained judicial minds which seek to balance competing interests to gauge whether a work is not obscene, and has, “artistic merit”. Again disposing of the petition and holding in favour of the author, the Court made reference to the contemporary morals of Indian society, which it also noticed, were “fast changing”. A convenient result therefore, backed by unfortunate reasoning.

Limiting the Hicklin test

It is not as if the criticisms of such an ad-hoc and content-by-content approach were not felt by the Court. In the same year as the Kakodar case, the Supreme Court made express reference to Udeshi’s case, when called to adjudge the legality of the pre-censorship of movies. The petitioners in K.A. Abbas v. Union of India argued that the mandatory certification necessary to any prior exhibition by the Cinematograph Act was unconstitutional as a prior-restraint. The Court, while holding the Act constitutional, laid down some guidelines that in its view, afforded reasonable safeguards. In its penultimate paragraph however, it contained some criticism that indicated a small but significant realisation that the law by and large contained vague obscenity standards. Its prescription revolted against any liberal conception of censorship, stating that Parliament should legislate more, as if to clinically separate the obscene from the moral. As we go along, we will discover the limits of law and of judicial eloquence to regulate the arts.

After an interregnum of about five years, the Supreme Court, in Samaresh Bose v. Amal Mitra, again faced its precedent and marked a significant departure from it by seeking to limit the applicability of the Hicklin test. Rather, it sought to make community standards the overreaching or controlling criteria to gauge obscenity. The Court in its inquiry, first focussed on certain prongs devised under a community standards grouping and only after this, did it proceeded to a pure analysis of obscenity under Section 292 and the Hicklin test. This was achieved by the Court stating that in order to determine the offence of obscenity, the judge should first place themselves in the position of the author to gauge the literary and artistic merit and thereafter place themselves in the position of a reader of every age group, not only children and those open to influences. Only after this should the inquiry on the Hicklin test proceed. This test or the tiered approach to gauge illegality appears persuasive, however again, in practice, requires subjective, content-by-content determinations.

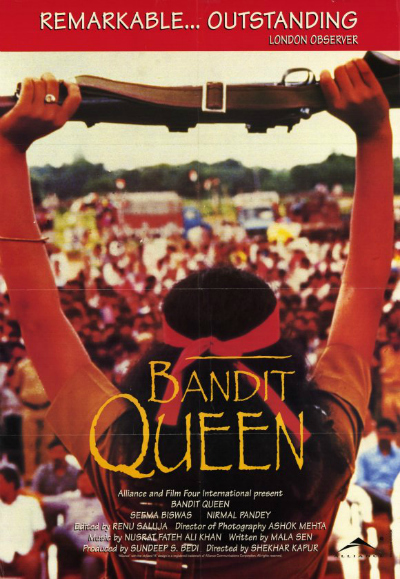

Even though the test in Samaresh Bose has not been followed, courts have evenly sought to apply its variations to gauge the artistic merit in a work while determining obscenity. In Bobby Art International, Etc v. Om Pal Singh Hoon, the Supreme Court, while adjudicating the appropriateness of the movie Bandit Queen being given a Central Board of Film Certification (“Censor Board”) certificate with an “A” rating, exhaustively analysed the theme of the movie. The Court held that the objections of the Censor Board that the movie depicted social evils could not be sustained as it was unavoidable in a movie which showed the consequent harm caused by it. Further, in Director General, Directorate v. Anand Patwardhan, the Supreme Court directed Doordarshan to screen the respondent’s documentary Father, son and Holy War and in doing so, sought to expressly apply “community standards” while not expressly overruling the Hicklin test.

Even though the test in Samaresh Bose has not been followed, courts have evenly sought to apply its variations to gauge the artistic merit in a work while determining obscenity. In Bobby Art International, Etc v. Om Pal Singh Hoon, the Supreme Court, while adjudicating the appropriateness of the movie Bandit Queen being given a Central Board of Film Certification (“Censor Board”) certificate with an “A” rating, exhaustively analysed the theme of the movie. The Court held that the objections of the Censor Board that the movie depicted social evils could not be sustained as it was unavoidable in a movie which showed the consequent harm caused by it. Further, in Director General, Directorate v. Anand Patwardhan, the Supreme Court directed Doordarshan to screen the respondent’s documentary Father, son and Holy War and in doing so, sought to expressly apply “community standards” while not expressly overruling the Hicklin test.

The resultant confusion in standards which may be applied to obscenity is evident from the Supreme Court’s reasoning in Ajay Goswami v. Union of India. These tests, which are chronologically listed, are prefaced in the judgement as “broad principles”. Not only are these principles broad, but their girth seems to have increased with time. Though the judgement in terms of legal articulation correctly notices past precedent, it also makes it evident that India, for a long period of time, had several legal standards to gauge obscenity, permitting subjectivity and preventing adequate notice of illegality to artists and authors.

Express adoption of community standards

This position in law seems to have undergone a dramatic change last year, with the Supreme Court ruling in Aveek Sarkar v. State of West Bengal. The ruling expressly discards the Hicklin test, stating that it is not good law. In its place, it adopts the more liberally oriented “community standards” test. However, the manner in which the Court applies the community standards test itself gives cause for concern. If one reads the judgement, the Court again examines the content in question and the social merit in the publication. Again, the result may be liberal, but the reasoning itself may only be a modest improvement on the Hicklin Test.

This is not to say that the express adoption of the community standards test in the Aveek Sarkar case is not cause for hope, however its promise is limited. While it does signify an express statement from the Supreme Court recognising the need for the greater liberty of artists and authors, it maintains the necessity for “artistic merit” or social need. The application of the community standards test can also be criticised on several other grounds but the major criticism is that it again permits subjectivity and a value-driven assessment by our higher judiciary.

Again, it needs to be emphasised that the High Court of Delhi has in two recent cases, by the application of Aveek Sarkar, refused to prohibit the exhibition of movies with Censor Board certificates. In both instances however, the Court gave substantial credence to the legality of the movies on the basis of the certificate for exhibition issued by the Censor Board. In the first case, Nandini Tewari and Another v. Union of India, the Court was asked to prohibit the exhibition of the movie Finding Fanny due to the name of the movie itself. The Court examined the term “fanny” as well as the term as it appeared in the dialogues of other movies in the past. It not only applied the Aveek Sarkar case but even earlier precedent to implicitly form a “community interest” and an “anticipated danger” test.

In the second case, Ajay Gautam v. Union of India, the High Court examined the contents of the movie PK, which the petitioner complained, mocked the Hindu religion and hence should be prohibited from exhibition. The Court again substantively appreciated the movie in question, heavily relying on the prior existence of a Censor Board certificate, and the nature of the movie, that is, a parody. Though the case is not per se concerned with obscenity, precedent on obscenity is bundled with larger free speech jurisprudence including the, “clear and present danger” test.

The limits of law

A review of legal precedent suggests that both the Hicklin test and the community standards test are not only fallible in some isolated instances but by their very nature permit subjectivity and value-based assessments. It has been my firm belief that any moral harm that is supposed to originate from movies, songs, paintings, or any other form of creative art is illusory. This moral harm is at the core of any justification for the offence of obscenity. Even if such an outlook is not shared by others, it is evident that obscenity to a large degree is a vague concept which will rely on a case-by-case determination, dependent on the facts of each case, in which a judicially trained mind (as opposed to an artistically inclined one) will examine the artistic merits and the potential illegality.

Though Indian case law to a large degree has drawn inspiration from the First Amendment precedent of the United States Supreme Court, it has failed to notice the dissent of Justice Brennan in Paris Adult Theatre I v. Slaton. Justice Brennan’s eloquence lays evident the limits of law, as it seeks to balance any purported moral harm with the liberty of artists. To end it is quoted below:

“Of course, the vagueness problem would be largely of our own creation if it stemmed primarily from our [p84] failure to reach a consensus on any one standard. But, after 16 years of experimentation and debate, I am reluctantly forced to the conclusion that none of the available formulas, including the one announced today, can reduce the vagueness to a tolerable level while at the same time striking an acceptable balance between the protections of the First and Fourteenth Amendments, on the one hand, and, on the other, the asserted state interest in regulating the dissemination of certain sexually oriented materials. Any effort to draw a constitutionally acceptable boundary on state power must resort to such indefinite concepts as “prurient interest,” “patent offensiveness,” “serious literary value,” and the like. The meaning of these concepts necessarily varies with the experience, outlook, and even idiosyncrasies of the person defining them. Although we have assumed that obscenity does exist and that we “know it when [we] see it,” Jacobellis v. Ohio, supra, at 197 (STEWART, J., concurring), we are manifestly unable to describe it in advance except by reference to concepts so elusive that they fail to distinguish clearly between protected and unprotected speech.”

(Apar Gupta is a partner at Advani & Co., and was recently named by Forbes India in its list of thirty Indians under thirty years of age for his work in media and technology law.)