Recently, a Delhi High Court judge initiated contempt proceedings against a legal news magazine that published a report which claimed that a nightclub in the capital was allowed to remain open beyond the licensed closing time because the judge’s son had an interest in the club.

Recently, a Delhi High Court judge initiated contempt proceedings against a legal news magazine that published a report which claimed that a nightclub in the capital was allowed to remain open beyond the licensed closing time because the judge’s son had an interest in the club.

‘Criminal contempt’, defined under Section 2(c) of the Contempt of Courts Act, 1971 as a criminal offence, is the act of communicating, either through spoken or written words or other visible representations, something that, among other things,

scandalises, or tends to scandalise, or lowers, or tends to lower, the authority of any court. Under Section 12 of the Act, criminal contempt can be punished with simple imprisonment up to six months or a fine up to Rupees Two thousand or both.

The somewhat old-fashioned rationale behind this power is that in order for the judiciary to carry out its functions, it was essential for the courts to be perceived as fair and unbiased. Let us look at five instances where courts have used this power to penalise communication in the media that has been critical of the integrity of judges.

1. Perspective Publications v. State of Maharashtra (1968)

Blitz, a weekly newspaper, had lost a suit in which a firm of architects claimed damages of Rs. 3 lakhs from them. Justice Tarkunde of the Bombay High Court had passed the decree. Later, an article that appeared in a publication brought out by Perspective Publications and written by its editor, alleged that the judgment had been decided in favour of the firm because Justice Tarkunde’s father, brother, and other relatives were partners and had a large pecuniary interest in the firm. They were found guilty of contempt of court and sentenced to a month of simple imprisonment and a fine of Rs. 1000. “The publication of a disparaging statement”, Justice Mukherjee held “will be an injury to the public if it tends to create an apprehension in the minds of the people regarding the integrity, ability, or fairness of the judge or to deter actual and prospective litigants from placing complete reliance upon the court’s administration of justice or if it is likely to cause embarrassment in the mind of the judge himself in the discharge of his judicial duties.”

2. In Re S. Mulgaokar (1978)

A letter was circulated among judges of the Supreme Court and the High Courts on drafting a code of ethics for judges. The Indian Express published the details of the letter and also commented on the character of the judges, specifically referring to some who lacked ‘moral courage’. The suit was dismissed and the article was not held to amount to contempt of court. Justice Krishna Iyer laid down six principles to determine if the publication of some matter amounts to contempt of court.

3. Court On Its Own Motion v. M.K. Tayal and Others (2007)

Mid-Day published an article with a cartoon which alleged that Justice Y.K. Sabharwal, a former Chief Justice of India had headed a Supreme Court bench which passed certain orders in the matter of sealing off commercial establishments in residential areas even though the sons of the Chief Justice had a vested interest in those commercial establishments. The article cast aspersions on the soundness of the judgement and imputed that the sons had benefitted from it. Following the publication, senior advocate R.K. Anand had submitted a copy of the paper to the Court and accused the newspaper of scandalising the judge and the Court. The Court took suo moto cognizance of the matter and the newspaper’s editor, publisher, resident editor, and cartoonist were held guilty of contempt of court. “The manner in which the entire incidence has been projected”, the Court held, “gives the impression as if the Supreme Court permitted itself to be led into fulfilling an ulterior motive of one of its members. It tends to erode the confidence of the general public in the institution itself.”

Mid-Day published an article with a cartoon which alleged that Justice Y.K. Sabharwal, a former Chief Justice of India had headed a Supreme Court bench which passed certain orders in the matter of sealing off commercial establishments in residential areas even though the sons of the Chief Justice had a vested interest in those commercial establishments. The article cast aspersions on the soundness of the judgement and imputed that the sons had benefitted from it. Following the publication, senior advocate R.K. Anand had submitted a copy of the paper to the Court and accused the newspaper of scandalising the judge and the Court. The Court took suo moto cognizance of the matter and the newspaper’s editor, publisher, resident editor, and cartoonist were held guilty of contempt of court. “The manner in which the entire incidence has been projected”, the Court held, “gives the impression as if the Supreme Court permitted itself to be led into fulfilling an ulterior motive of one of its members. It tends to erode the confidence of the general public in the institution itself.”

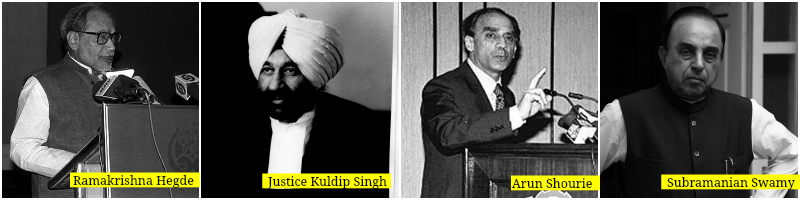

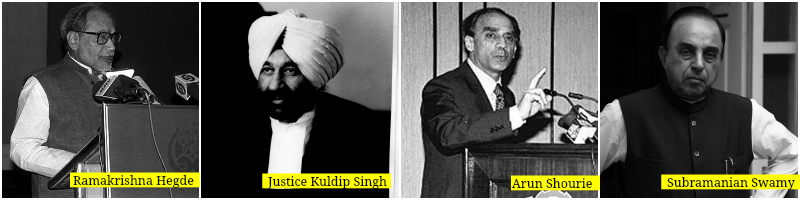

4. Dr. Subramanian Swamy v. Arun Shourie (1990)

Justice Kuldip Singh, then a judge of the Supreme Court, was appointed the chairman of a commission of inquiry to probe into allegations of corruption against Ramakrishna Hegde, the former Chief Minister of Karnataka. When the commission released its report, it refuted all the allegations. The Indian Express published an article titled “If Shame Had Survived”, criticising the report for being “deferential” to the Chief Minister and accusing Justice Singh of “inventing theories and probabilities” to argue against the allegations. The article also highlighted how Justice Singh had failed to include the evidence of the key witness in the case and said that “If there had been any sense of honour or shame, a Judge would never have done any of this.” Subramanian Swamy filed a contempt petition against Arun Shourie, who was the editor of the newspaper, contending that the editorial was a scandalous statement in respect of a sitting judge of the Supreme Court. Even though the Court took suo moto cognizance of the matter, the petitions were dismissed, partly because the law was amended during the course of the proceedings to include truth as a defence and partly because Justice Singh, as member of a commission of inquiry, was not a court for the purposes of the contempt law.

5. Shri Surya Prakash Khatri & Another v. Smt. Madhu Trehan and Others, 2001

A fortnightly magazine called Wah India published an article listing fourteen judges of the Delhi High Court and evaluated them on parameters of punctuality, knowledge of the law, integrity, quality of judgments, manners in court, and receptiveness to arguments. The evaluation was apparently based on a survey that took in the opinions of fifty “senior lawyers”. The Delhi High Court issued a notice against the magazine’s Editor-in-Chief and directed the Delhi police to ensure that copies of the allegedly offensive issue were withdrawn from newsstands and the shops that sold it. Copies of the issue that had not been circulated were thus seized and confiscated. The Court held that prima facie contempt had been committed by the respondents because the ranking of the judges amounted to scandalising the judiciary. The Court also refused the apologies that were tendered by the accused.

The law on criminal contempt of court in India has been invoked against the press several times because of perceived insults to the judiciary. In Germany, France, Belgium, Austria, and Italy, however, there is no concept of criminal contempt of court and the only options that the judges have are in their personal capacity: either file a criminal complaint or institute an action for libel. In the United Kingdom, even though the criminal offence was only abolished in 2013, the last successful prosecution happened in 1931. Various Indian judgments on the issue have been quick to point out that “scandalising the judiciary” amounts to contempt under the statute but isn’t it time that the judiciary made a conscious move to give a more liberal interpretation to the law? Healthy debate and criticism are necessary in a democracy and there is no reason the judiciary should be above it.

(Prapti Patel is a student of the Indian Law Society’s Law College in Pune.)

On December 3, 2014, the Supreme Court of the United States of America heard the case of Young v. United Parcel Service, a case filed by Peggy Young of Maryland. An employee of the respondent company, she was placed on unpaid leave when she became pregnant in 2006, resulting in the loss of her medical benefits. A district judge and the U.S. Court of Appeals have already ruled in favour of the shipping company, but activists in favour of Young are hopeful that the Supreme Court will take a different stand on the issue.

On December 3, 2014, the Supreme Court of the United States of America heard the case of Young v. United Parcel Service, a case filed by Peggy Young of Maryland. An employee of the respondent company, she was placed on unpaid leave when she became pregnant in 2006, resulting in the loss of her medical benefits. A district judge and the U.S. Court of Appeals have already ruled in favour of the shipping company, but activists in favour of Young are hopeful that the Supreme Court will take a different stand on the issue. In Ram Bahadur Thakur (P) Ltd. v Chief Inspector of Plantations, a female worker employed at the Pambanar Tea Estate was denied maternity benefits on the grounds that she had actually worked for 157 days instead of the 160 days required to qualify for them. The Supreme Court, however, held that for the purposes of computing maternity benefits, all days including Sundays and unpaid holidays must be taken into consideration.

In Ram Bahadur Thakur (P) Ltd. v Chief Inspector of Plantations, a female worker employed at the Pambanar Tea Estate was denied maternity benefits on the grounds that she had actually worked for 157 days instead of the 160 days required to qualify for them. The Supreme Court, however, held that for the purposes of computing maternity benefits, all days including Sundays and unpaid holidays must be taken into consideration. In Municipal Corporation of Delhi v. Female Workers’ (Muster Rolls) and Another, the Municipal Corporation of Delhi stated that it granted maternity leave to its regular female workers but not to the daily wage ones, that is, the ones on the muster rolls. The respondents argued that the practice was unfair as there was hardly any difference in the work allotted to female workers who were regular and those who were on daily wage. Accepting the contention, the Supreme Court upheld the right of female construction workers to be granted maternity leave by extending the scope of the Maternity Benefits Act, 1961 to daily wage workers.

In Municipal Corporation of Delhi v. Female Workers’ (Muster Rolls) and Another, the Municipal Corporation of Delhi stated that it granted maternity leave to its regular female workers but not to the daily wage ones, that is, the ones on the muster rolls. The respondents argued that the practice was unfair as there was hardly any difference in the work allotted to female workers who were regular and those who were on daily wage. Accepting the contention, the Supreme Court upheld the right of female construction workers to be granted maternity leave by extending the scope of the Maternity Benefits Act, 1961 to daily wage workers.