Conflict zones, as this column has pointed out earlier, are particularly difficult places for human rights lawyers to work. In the Bastar region in southern Chhattisgarh, years of the Maoist insurgency and the counter-operation by the Indian state have created a battle zone where even normal life is subject to the oversight of security forces. In Jagdalpur, I was advised not to step out after sunset as I could be picked up by the CRPF.

Conflict zones, as this column has pointed out earlier, are particularly difficult places for human rights lawyers to work. In the Bastar region in southern Chhattisgarh, years of the Maoist insurgency and the counter-operation by the Indian state have created a battle zone where even normal life is subject to the oversight of security forces. In Jagdalpur, I was advised not to step out after sunset as I could be picked up by the CRPF.

Paradoxically, for the wide publicity it gets, there is little in-depth information or reportage about Bastar. The legal issues that affect the region have not been understood or documented in detail.

It is in this situation that a group of committed human rights lawyers has been quietly working towards documenting the plight of undertrials in Bastar and providing them with legal aid at the trial courts. The Jagdalpur Legal Aid Group (or “JagLAG” as they call themselves), is an all-women team of lawyers based out of Jagdalpur, the headquarters of Bastar district, where they are fighting state apathy, disempowerment, and patriarchy while helping the predominantly adivasi population secure access to justice.

Earlier this year, I interacted with the group at their office in Jagdalpur and visited the courts and the jail there. JagLAG is unique in that its members are all graduates from major law universities and have chosen to litigate at the trial courts in Bastar over other, more lucrative, options. Shalini Gera, 44, is the oldest member of the group and a graduate from Delhi University, and had previously been working with senior advocate Sudha Bharadwaj in Bilaspur. The others, Guneet Kaur, Isha Khandelwal, and Parijatha Bhardwaj, are recent graduates from Indian and foreign universities. For all of them, JagLAG was the first experience at practising law at the trial courts. In an unfamiliar location, theirs has been a trial by fire of sorts.

Early days of gathering data

JagLAG had its genesis in conversations that took place in Mumbai and Delhi among lawyers and activists around the possibility of a systematic legal intervention in Bastar. Major human rights abuses, such as the Soni Sori case, had come to light from the region. The intervention aimed at documenting human rights issues from the ground and providing legal aid to undertrials and adivasis who had been framed as “Naxals”. As a result of these conversations, a few advocates committed themselves to providing funding and mentorship for the group, with the aim of supporting an effort at ensuring access to justice in this region.

The Bastar region, where the group works, is comprised of five districts – Bastar, Dantewara, Kanker, Sukma, and Bijapur. JagLAG, being the first such intervention in the area, has had to learn the ropes from scratch. They spoke to local lawyers to get a sense of the courts and the cases being handled, and used empirical data obtained through the Right to Information Act to substantiate the anecdotes.

The RTI applications about court and prison statistics revealed a complete breakdown of the criminal justice system in Bastar. The jails were severely overcrowded. While the average occupancy in jails across the country is 112%, the corresponding figures ranged from 255% at the Jagdalpur Central Jail to an astounding 428% at the Kanker District Jail. Most of the prisoners were illiterate adivasi men between the ages of 18 and 30 and an overwhelming majority were undertrials.

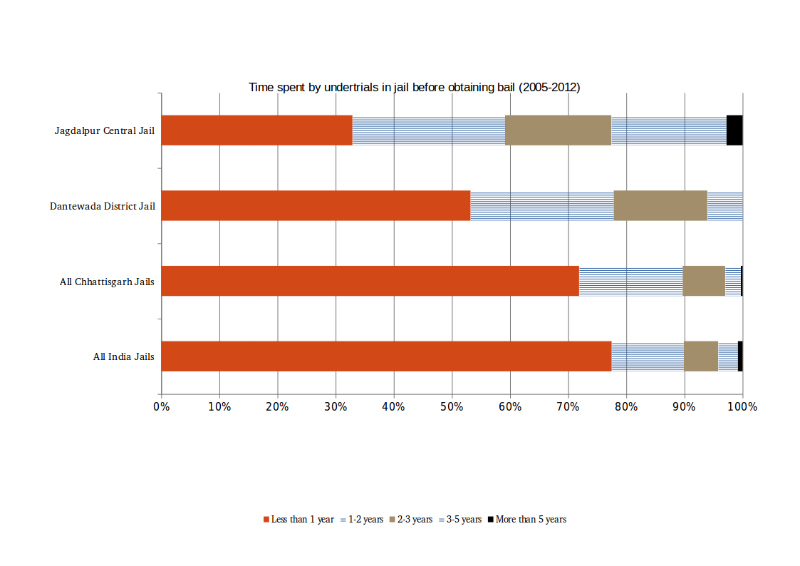

An analysis of the case disposal statistics between 2005 and 2012 revealed that two-thirds of undertrials in Jagdalpur had to spend between two and five years in prison before receiving bail, while on an average, across the country, 75 per cent of undertrials spend less than a year in prison before receiving bail. An astounding 96 per cent of the cases between 2005 and 2012 ended in acquittal, indicating that in most cases, the police had mostly framed innocent adivasis and there was no evidence to indicate any actual links with the Maoists.

Trademark Naxalite cases

Following up, JagLAG began to track the cases of those who had been incarcerated the longest, to identify the blocks in the system. As they interacted with more prisoners and went through their files, patterns began to emerge. Most of them had been incarcerated in what Shalini described as “trademark Naxalite cases” – allegations of being involved in Maoist activities or conspiracy – including charges under Sections 302 or 307 and 149 of the Indian Penal Code, along with Sections 25 and 26 of the Arms Act, 1959 and Sections 3 and 4 of the Explosives Act, 1884. In addition, provisions of the Unlawful Activities Prevention Act, 1967 and the Chhattisgarh Special Public Security Act, 2005 are also invoked. Many of the prisoners who had been in jail for a long time had not even applied for bail, due to a combination of circumstances.

Bringing in families to file for bail

Local lawyers are reluctant to file for bail, given that the sections involved are non-bailable and the charges are grave, making it rather difficult to obtain bail from a trial court. In addition, the prisoners are usually residents of remote villages and given the long distances and poor transportation facilities in the region, it is difficult for their families to visit the jail or the lawyers. As families was unable to take an active role in the case, the local lawyers lose interest and the cases – and the undertrials involved – would languish for years.

The Jagdalpur Legal Aid Group – (from left to right) Guneet Kaur, Isha Khandelwal, Shalini Gera, and Parijatha Bhardwaj

The group began their legal aid work by filing bail applications on behalf of these undertrials. This intervention, including working with the lawyers currently representing the undertrial prisoners and persuading them to file for bail and bringing the families back on board, was a learning experience. They visited the families in their villages rather than rely on them – mostly poor, illiterate adivasis – to make the long and expensive commute all the way to Jagdalpur. However, local security concerns and the looming threat of police action have forced them to restrict field visits in favour of courtwork. They also provide support to fact-finding investigations into grave human rights violations, such as the PUDR investigation into the Sarkeguda extra-judicial killings of 2012, and represent victims of custodial torture, violence, and death at enquiries before the sub-judicial magistrate. Incidentally, on the day of my visit, Guneet and Shalini had just arrived after a day’s trip to Dantewara, to record the affidavits of villagers in a case of extra-judicial execution.

Problems with data and procedure

From the beginning, JagLAG faced several challenges in their work. The initial set of RTI applications revealed that data was recorded in different ways in different places. For instance, while the jail records were referenced by crime numbers, the court records used case numbers, and matching the two took some effort. Many of the long-pending cases that they took up already had lawyers, and much time was spent in tracking down people and their cases, as well as persuading the current set of lawyers to file applications or hand over the cases.

Local procedural requirements also made simple processes, like the filing of a bail application, extremely onerous. The criminal court rules of practice in Chhattisgarh require that while applying for bail, an affidavit had to be filed by a person other than the accused, who was conversant with the facts of the case. Usually, this was a close relative who resides far away from the court and the lawyer. The bail application cannot be filed until such a person has been located and the affidavit filed. JagLAG therefore had to re-calibrate its strategy and adopt more realistic goals about the number of cases they planned to take up. At present, they have taken two cases to the High Court and have handled several more at the various trial courts.

The group’s successes have also exposed the rot within the system. One of their early achievements was securing bail for two undertrials who had been incarcerated for six years, without their names even appearing on the chargesheet. Shockingly, the bail was only granted on a surety of Rs. 10,000 which resulted in the individuals concerned remaining in jail for another ten months while they contacted relatives and raised the money. An application filed under Section 440 of the Code of Criminal Procedure, to reduce the bond amount, remains pending before the court. In another case, they managed to get bail for three arrested persons at the remand stage itself – something that, despite being permitted under law, was almost impossible to do in Bastar.

Threats to their safety

The rigidly binary nature of public discourse in conflict areas means that anyone who does not espouse the State’s views is seen as siding with the opposition. In Bastar, this has meant that the members of JagLAG have been branded as “Naxalite supporters” or “sympathisers” by the administration and the police, for trying to higlight human rights abuses by the State. Consequently, they work under a constant cloud of threats to their safety, and hostility from the courts. Working as ‘outsiders’ in Bastar has not been easy: they have also faced hostility from fellow lawyers, who view them suspiciously because of their model of human rights lawyering, where they blend activism with court work, and also see JagLAG as competition because do not charge for their services. Isha says, “People keep attributing ulterior motives to us all the time. It’s difficult to explain the concept to them.” In addition, they began work with no contacts or local networks, and have had to build these up from scratch. However, being outsiders with no familial or other investments in the area has also enabled them to take more aggresive stances against the State which local lawyers would have been reluctant to do. As a group, JagLAG is always conscious about the danger of their advocacy work appropriating the agency of the adivasi communities they are representing as lawyers. Says Guneet, “It’s something that goes on all the time in my head – in our role as civil society here, we shouldn’t make decisions [on behalf of the adivasis] that aren’t ours to make.”

The challenges of patriarchy

Being women in a partiarchal, all-male structure – there are almost no women among court staff and at the Bar in Jagdalpur – means that they are at the receiving end of condecension and a patronising attitude from lawyers and judges alike. Parijatha says, “We have inexperience going against us, but this gets compounded by the fact that we’re women.” Over the last couple of years, they have managed to negotiate an uneasy space for themselves, while in the process breaking stereotypes about how women are expected to work and behave in public spaces. Guneet, Isha, and Parijatha have recently featured in Forbes India‘s “30 under 30” list for their efforts.

Sustainability

JagLAG is supported, financially and professionally, by a number of lawyers around the country, and they are grateful for the mentorship that has helped them work in a very difficult location with very little experience. All four of them have found the work to be an enriching process. Says Guneet, “There were times we would call [the senior lawyers] up at night with minute legal queries and they were always very encouraging and helpful.”

The group has not fully considered its future, given that their experiences have been different from what they had originally planned. However, they are optimistic that they will be able to sustain themselves and include more local lawyers in the process. Shalini concludes, “The key to replicating and making this sort of initiative sustainable in other places is to involve local people as a core part of the work. That is something that we look forward to doing in the future.”

(Manish is a 2013 graduate of NLSIU, Bangalore and works on issues of access to justice. He is currently based in Ahmedabad.)