In 1960, John T. Scopes, a geologist, returned to Dayton, a town in Tennessee where 35 years earlier, he had been convicted of a crime. Instead of being scorned and spurned, he was celebrated and awarded a key to the city. He had returned to attend the premiere of Inherit the Wind, a film that had been made on his trial. The film, boasting of some of the biggest names in Hollywood, was supposed to tell the true story of the Scopes ‘Monkey’ Trial, but it didn’t. Its intention was to use the trial to make a very different point. Then again, even the original trial was not much more than a farce.

In 1960, John T. Scopes, a geologist, returned to Dayton, a town in Tennessee where 35 years earlier, he had been convicted of a crime. Instead of being scorned and spurned, he was celebrated and awarded a key to the city. He had returned to attend the premiere of Inherit the Wind, a film that had been made on his trial. The film, boasting of some of the biggest names in Hollywood, was supposed to tell the true story of the Scopes ‘Monkey’ Trial, but it didn’t. Its intention was to use the trial to make a very different point. Then again, even the original trial was not much more than a farce.

The making of the film trial

On January 21, 1925 Rep. John Washington Butler introduced a bill in the Tennessee House of Representatives “prohibiting the teaching of the Evolution Theory in all the Universities, and all other public schools of Tennessee, which are supported in whole or in part by the public school funds of the State, and to provide penalties for the violations thereof.” The Butler Act, as it came to be known, was enacted six days later. This ban on teaching evolution in public schools in Tennessee was reported in newspapers all over America and came to the notice of a young organisation in New York called the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU), which advocated for freedom of thought and expression regardless of political leanings. It put out a notice in newspapers inviting any teacher from Tennessee to challenge the law. “We are looking for a Tennessee teacher who is willing to accept our services in testing the law in the courts,” it said. “Our lawyers think a friendly test can be arranged without costing a teacher his or her job. Distinguished counsel have volunteered their services. All we need is a willing client.” Enter George Washington Rappleyea.

George Rappleyea, the man who wanted to put Dayton on the map.

Rappleyea was the Superintendent of the financially floundering Cumberland Coal and Iron Company in Dayton, Tennessee. He read ACLU’s notice and the very next day, met a group of influential men of Dayton and suggested that the law should be challenged in their town. He foresaw that the resulting trial would bring national attention and definitely put Dayton on the map – something that must have appealed to everyone as Dayton was going through hard times. Rappleyea convinced a young schoolteacher called John T. Scopes to be the challenger even though Scopes couldn’t remember if he had actually ever taught evolution in his classroom.

None of these events leading up to the trial are shown in Stanley Kramer’s Inherit the Wind. The film begins with Bertram Cates (Dick York), a fictionalised version of John Scopes, teaching evolution openly in a Southern town called Hillsboro. While Scopes was ambivalent about the law until Rappleyea convinced him to challenge it, Cates is presented almost as a heroic crusader completely unwavering in his noble convictions. None of the prior machinations that led to the original trial are even alluded to.

A well-known reporter named E.K. Hornbeck (Gene Kelly) comes to Hillsboro to cover the trial. Amidst his sarcastic quips and witty one-liners, he informs Cates that his employer, the Baltimore Herald, is willing to finance his defence. The acerbic, cynical Hornbeck is the fictional cognate of H.L. Mencken, the famous and influential reporter who covered the Scopes ‘Monkey’ Trial. Mencken was a staunch atheist and detested fundamentalists and “southern yokels”, calling them “ignoramuses” and “morons”. He was also a racist and anti-Semite who distrusted democracy deeply, which made him a natural opponent of the prosecution attorney: William Jennings Bryan.

Above, Gene Kelly and Dick York playing E.K. Hornbeck and Bertram Cates in Inherit The Wind (1960). Below, H.L. Mencken the journalist and John T. Scopes the geologist (right), the real-life figures that these actors portrayed.

The prosecuting attorney in Inherit the Wind, Matthew Harrison Brady (Fredric March) is a Bible-thumping, chicken-devouring, moralising caricature of Bryan. Everything about the look of the character – from his baldpate to his pince-nez to the cut of his shirt – is modeled to be identical to that of Bryan’s. In many ways ahead of his time, Bryan had spent a lifetime fighting for farmers, women’s suffrage, and campaign finance reforms, and raising his voice against imperialism and corrupt corporate practices in the early 1900s. But all we see is a screaming blowhard trying desperately to cling to his woefully outdated beliefs. A Bible literalist, his distaste for the theory of evolution came not just from his religious views but also from his mistaken conflation of Darwin’s theory of natural selection to the concept of Social Darwinism – a system of thought that often rationalises racism, eugenics, fascism, and imperialism.

Above, Spencer Tracy and Fredric March playing Mathew Harrison Brady, the prosecuting attorney and Henry Drummond, the defense attorney in a scene from Inherit The Wind (1960). Below, Clarence Darrow and William Jennings Bryan, the lawyers who came up against each other in the Scopes ‘Monkey’ Trial.

Cates’ defense attorney is Henry Drummond (Spencer Tracy), a fictionalised version of Clarence Darrow, who, in 1925 was perhaps the most famous lawyer in the country, having argued a number of high profile cases. Like Mencken, Darrow was a modernist and atheist, inspired by the writings of Nietzsche, Darwin, Marx, Freud, and Voltaire. He had once been a friend of Bryan and had even supported him in his first presidential campaign, but the two had later parted ways due to the stark differences in their thinking (a fact that is reflected in the film as well). When he heard Bryan had joined the prosecution team, Darrow immediately decided to join the defence to battle “the idol of all Morondom”.

The greatest show in America

Scenes from Inherit The Wind (1960)

The film accurately portrays the media circus this trial became. In an unprecedented turn of events WGN Radio managed to obtain the rights to rearrange the way the courtroom was set up. Despite a burning heat wave in Dayton that year, hundreds of people crowded into the courtroom to witness this clash of titans and their ideas. Journalists sat with typewriters and microphones recording every instant of this great show as if it were a boxing match. Outside the courtroom was a veritable carnival centred around the trial. Shops sold monkey-themed memorabilia, songs written about the trial were sung on the streets, and a pet chimpanzee named Joe Mendy was brought out in a new suit everyday for the amusement of one and all. This fanfare is faithfully portrayed in Inherit the Wind. The people of Dayton, however, are not.

The film paints the residents of Hillsboro (read Dayton) as an angry, ignorant mob ready to lynch Cates. This was, by all accounts, patently untrue. Even Mencken wrote, “The town, I must confess, greatly surprised me. I expected to find a squalid Southern village, with darkies snoozing on the horseblocks, pigs rooting under the houses and the inhabitants full of hookworm and malaria. What I found was a country town full of charm and even beauty […] Nor is there any evidence in the town of that poisonous spirit which usually shows itself when Christian men gather to defend the great doctrine of their faith. […] On the contrary, the Evolutionists and Anti-Evolutionists seem to be on the best of terms, and it is hard to distinguish one group from another.”

From the beginning, Judge Raulston had instructed the jury, prosecution, and defence to keep the trial about the case in hand – Scopes’ contravention of the Butler Act – and not to argue whether the law itself was just or unjust. Of course, neither Darrow nor Bryan had any intention of obeying the judge. As far as both were concerned, this was the most important philosophical and cultural tipping point in their lifetimes. It was the debate that would decide what civilisation itself stands for. Scopes’ ultimate fate meant very little to Darrow. In fact, he hoped that Scopes would be found guilty so that he could appeal to a higher court and argue the merits of the Butler Act there.

The verdict

In the end, the jury in the film, like the one in real life, returns a verdict of “guilty”. And, like the judge in the actual trial, the one in the film goes easy on the defendant, keeping in view the mood of the nation. Cates, like Scopes, is fined $100 and given no jail time. In a sense, both Bryan and Darrow got what they wanted. Bryan got a guilty verdict and, hence, a moral victory, even though he was displeased with the inadequacy of the sentence. Darrow got the opportunity to argue the validity of the law at the Tennessee Supreme Court.

In the film, as indeed in real life, the trial was not really about the case at hand but an opportunity to argue about differing viewpoints, the lawyers on both sides representing not the state and the accused, but two opposing schools of thought. The courtroom became a venue for debating ideology, a soapbox atop which each lawyer, acting as the spokesperson for his side, could stand and deliver loud and impassioned political speeches. So impassioned, in fact, that Brady quite literally screams himself to death. He collapses in the courtroom and dies of a “busted belly”. It is the death knell of an ideology whose time has come. In real life, Bryan had died five days after the trial was over. This too, is a minor liberty.

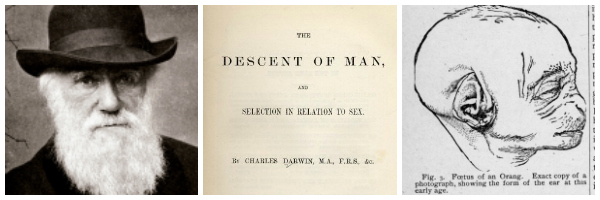

Charles Darwin, the title page of The Descent of Man and Selection In Relation to Sex (1871), and a figure from the book.

The film, therefore, takes all the liberties it deems necessary to make its statement. A lot of the complexities in the characters are done away with in order to reduce them from fully-fleshed people to mere archetypes, the nuances in the arguments and ideas presented are erased to tell a more straightforward story, and a number of important facts that are necessary to contextualise the story correctly are conveniently sacrificed to make a point. And what was the point?

If your answer to that question is something along the lines of “scientific and rational thought is superior to blind faith”, then you’re wrong. Inherit the Wind was adapted from a 1955 play of the same name written by Jerome Lawrence and Robert E. Lee. In an interview, Lawrence had said, “We used the teaching of evolution as a parable, a metaphor for any kind of mind control. It’s not about science versus religion. It’s about the right to think.” And why did the writers suddenly feel so compelled to make this point about the right to think? The answer, in a word, is McCarthyism.

McCarthy vs. Free Thought

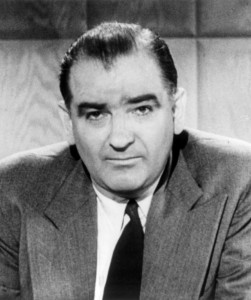

In the late 1940s, Americans were gripped by the fear of that giant, looming, faceless threat advancing from around the globe: Communism. The Red Scare sent shivers down the spines of patriots and lovers of the American dream. In the 1950s, Senator Joseph McCarthy entered the scene, took that latent fear and whipped it up to the highest levels of mass hysteria and moral panic by painting communists as traitors and Soviet spies living among Americans and infiltrating positions of power and influence. He began a fearsome campaign to identify and convict them. Thousands of Americans would be publicly named, questioned, interrogated, and threatened based on next to no evidence. It was akin to being labeled a terrorist today – they were put on a watchlist, their private lives were investigated, they lost their jobs and became social pariahs. It was one of the darkest moments in modern American history, much like the Emergency was for India.

Joseph Raymond McCarthy, who served as a U.S. Senator between 1947 and 1957, was noted for his claims that there were large numbers of Communists and Soviet spies and sympathisers inside the United States federal government and elsewhere.

In 1953, Arthur Miller, who was investigated by McCarthy, used the 17th century Salem witch trials to make a lasting statement on McCarthyism in his play The Crucible. This inspired Lawrence and Lee to write Inherit the Wind. Speaking of the Scopes ‘Monkey’ Trial, Lawrence said, “We thought, ‘Here’s another time when there was a corset on your intellectual and artistic spirit.” It was, therefore, perhaps fitting that director and producer Stanley Kramer hired Nedrick Young, a blacklisted screenwriter, to assist in adapting the play for the big screen.

Fact and fiction

At the end of the film, it is revealed that Drummond is actually a practicing Christian. Hornbeck is taken aback and berates him strongly. Drummond says he pities Hornbeck and asks him, “You don’t need anything, do you? People. Love. An idea just to cling to. You poor slob. You’re all alone. When you go to the grave there won’t be anyone to pull the grass up over your head. Nobody to mourn you. Nobody to give a damn. You’re all alone.” Hornbeck replies: “You’re wrong, Henry. You’ll be there. You’re the type. Who else would defend my right to be lonely?” This Voltaire-esque reply is one of the most poignant parts of the film, and in a way, its most moving comment on the McCarthy era. The loneliness of having an unpopular opinion is frightening, but the right to have an independent thought is one that should be defended zealously. The film closes with Drummond picking up a copy of the Bible and Darwin’s The Descent of Man, thumping them together and walking out of the courtroom, showing in no uncertain terms that it is possible for two opposing ideas to live together.

The Tennessee Supreme Court overturned Scopes’ conviction on January 15, 1927, not on the grounds of the unconstitutionality of the Butler Act, but on a relatively minor technicality. Judge Raulston had imposed the $100 fine. However, under the constitution of Tennessee, any fine in excess of $50 has to be assessed by a jury. Reversing the lower court’s judgment, the Tennessee Supreme Court stated, “We see nothing to be gained by prolonging the life of this bizarre case. On the contrary, we think the peace and dignity of the State, which all criminal prosecutions are brought to redress, will be better conserved by the entry of a nolle prosequi herein. The Butler Act would remain in force for 40 more years. It was finally repealed on May 17, 1967.

Inherit the Wind is, therefore, a film about an actual trial, but it isn’t really about the trial. The actual trial was about a man who was accused of committing a crime, but it wasn’t really about the man or the crime. It was a platform for the voicing of opinions on larger questions. With the help of carefully planned and calculated moves made right from the beginning, the trial had ceased to be a process of dispensing justice and was turned into a dais for making political speeches. In much the same way, Inherit the Wind took the events and personalities that shaped the trial, shaved off the inconvenient bits that came in the way of the point it was trying to make, and ultimately presented an inaccurate version of what happened.

It is perhaps the only instance of the real trial being as much of a fiction as the celluloid trial.

(Sayak Dasgupta wanders around myLaw looking for things to do.)

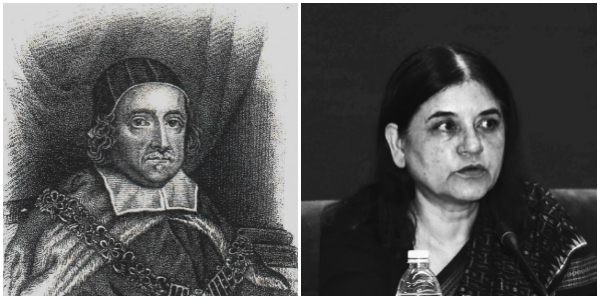

Sir Matthew Hale, one of England’s greatest jurists, was a simple, humble, and fastidiously honest man. In fact, so unimpeachable was his character that, despite being a royalist who defended the opponents of the Commonwealth of England during the English Civil War, he was still appointed a justice of the common pleas by Oliver Cromwell when the Commonwealth came to power. When the Restoration happened, the King appointed him Chief Baron of the Exchequer, even though he had held office in the government of his mortal enemies. Hale, it is said, had no desire to receive the knighthood, so he literally had to be tricked into it (Lord Clarendon invited Hale to his house where the King was waiting to knight him on the spot).

Sir Matthew Hale, one of England’s greatest jurists, was a simple, humble, and fastidiously honest man. In fact, so unimpeachable was his character that, despite being a royalist who defended the opponents of the Commonwealth of England during the English Civil War, he was still appointed a justice of the common pleas by Oliver Cromwell when the Commonwealth came to power. When the Restoration happened, the King appointed him Chief Baron of the Exchequer, even though he had held office in the government of his mortal enemies. Hale, it is said, had no desire to receive the knighthood, so he literally had to be tricked into it (Lord Clarendon invited Hale to his house where the King was waiting to knight him on the spot).