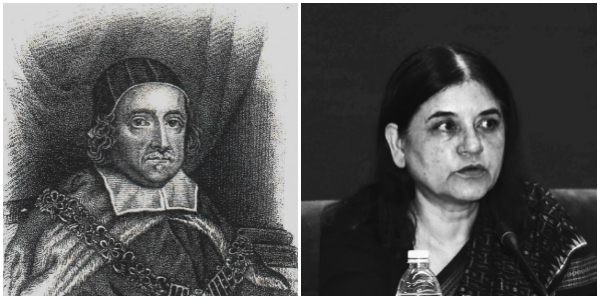

Sir Matthew Hale, one of England’s greatest jurists, was a simple, humble, and fastidiously honest man. In fact, so unimpeachable was his character that, despite being a royalist who defended the opponents of the Commonwealth of England during the English Civil War, he was still appointed a justice of the common pleas by Oliver Cromwell when the Commonwealth came to power. When the Restoration happened, the King appointed him Chief Baron of the Exchequer, even though he had held office in the government of his mortal enemies. Hale, it is said, had no desire to receive the knighthood, so he literally had to be tricked into it (Lord Clarendon invited Hale to his house where the King was waiting to knight him on the spot).

Sir Matthew Hale, one of England’s greatest jurists, was a simple, humble, and fastidiously honest man. In fact, so unimpeachable was his character that, despite being a royalist who defended the opponents of the Commonwealth of England during the English Civil War, he was still appointed a justice of the common pleas by Oliver Cromwell when the Commonwealth came to power. When the Restoration happened, the King appointed him Chief Baron of the Exchequer, even though he had held office in the government of his mortal enemies. Hale, it is said, had no desire to receive the knighthood, so he literally had to be tricked into it (Lord Clarendon invited Hale to his house where the King was waiting to knight him on the spot).

For all his virtues, though, Hale was as much of a fusty old antiquarian when it came to women, as you would expect from a privileged, white, devoutly Puritan Englishman from the 1600s. In a letter to his granddaughters, he wrote longingly of a time when “the education and employment of young gentlewomen was religious, sober, and serious, their carriage modest and creditable was their habit and dress” and “when they came to be disposed of in marriage, they were themselves a portion whether they had little or much, and could provide for and govern a family with prudence and discretion, and were great helps to their husbands, and knew how to build up a family, and accordingly were instruments in it”. He bemoaned how times had changed and “young gentlewomen learn to be bold, talk loud and more than comes to their share, think it disparagement for them to know what belongs to good housewifery, or to practise it, make it their business to paint or patch their faces, to curl their locks, and to find out the newest and costliest of fashions.” He wrote that he would never allow his granddaughters to be like this, that he would train them to be “good wives and better portions to your husbands than the money you bring, if it were double to what I intend you, for you will be builders up of a house and family, not destroyers of it”. Above all, he wanted them to be “good examples to others, and be thereby a means to take off the reproach that justly enough lies upon the generality of English gentlewomen, that they are the ruin of families”.

Like most men of the time, Hale saw women as some sort of loveable hybrid between a trainable pet and an obedient servant, who should be strictly controlled lest they go out of hand. It is perhaps somewhat revealing that after his wife died, Hale married his housekeeper, Anne Bishop, whom he described in his will as “most dutiful, faithful and loving”, words that can also be used to describe an adoring butler or a loyal dog.

“No longer enough to create further exceptions”

Four centuries of faith in wedding vows forming permanent consent for sex. Mathew Hale (left), when he was Chief Justice of the King’s Bench and Union Minister for Women and Child Development, Maneka Gandhi. Maneka Gandhi’s image is from the Press Information Bureau.

Perhaps Hale’s most famous work as a legal scholar is the Historia Placitorum Coronæ or The History of the Pleas of the Crown, which was published in 1736 (60 years after his death, despite an instruction in his will clearly stating that none of his manuscripts were to be published posthumously) and is considered a seminal work in the development and evolution of common law. It was in this book that he wrote the now (in)famous line that had been used until relatively recently in most common law countries to defend marital rape:

“But the husband cannot be guilty of a rape committed by himself upon his lawful wife, for by their mutual matrimonial consent and contract the wife hath given up herself in this kind unto her husband, which she cannot retract.”

The husband, then, by virtue of marriage, gained complete right over his wife’s body. Wedding vows were meant to be a form of permanent consent for sex. It would not be a stretch to say that for most women at the time, the bond of marriage was akin to bonded servitude mixed with sexual slavery.

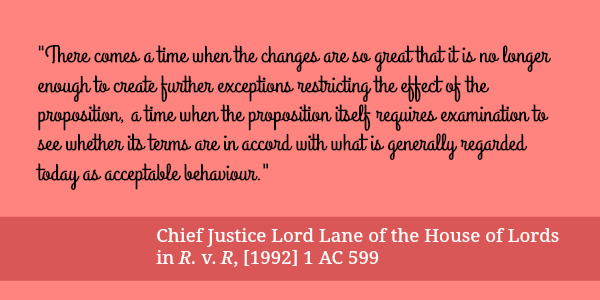

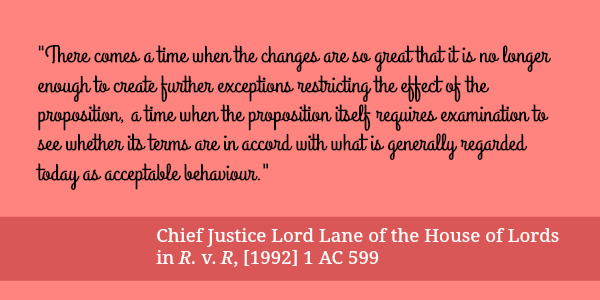

This would be the norm in England for the next two centuries, but changes in social attitudes towards marriage began to make the marital exemption to rape seem increasingly more ridiculous with every passing year. In 1990, the Law Commission in England released the Working Paper No. 116 on Rape within Marriage in which it recommended unequivocally that the exemption should be abolished. But the final death knell for the spousal exemption came in 1991 with the House of Lords’ landmark decision in R. v R, in which the court held that “Hale’s proposition is based on a fiction and moreover a fiction which is inconsistent with the proper relationship between husband and wife today.” The judges observed that “courts have been paying lip service to the Hale proposition, whilst at the same time increasing the number of exceptions, the number of situations to which it does not apply. This is a legitimate use of the flexibility of the common law which can and should adapt itself to changing social attitudes,” but then added the powerful line: “There comes a time when the changes are so great that it is no longer enough to create further exceptions restricting the effect of the proposition, a time when the proposition itself requires examination to see whether its terms are in accord with what is generally regarded today as acceptable behaviour.”

On the question of whether the court should step aside to leave the matter to the Parliamentary process, the House of Lords stated: “This is not the creation of a new offence, it is the removal of a common law fiction which has become anachronistic and offensive and we consider that it is our duty having reached that conclusion to act upon it.”

With these words, England removed the marital exception to the crime of rape. In the United States, states had begun to remove this exception since the 1970s, and by 1993, all 50 states had done so. By the dawn of the 21st century, marital rape was a crime in most European nations. Our neighbour Bhutan had declared it a crime as far back as 1996, and Nepal followed suit 10 years later. Today, marital rape is a crime in the majority of the countries in the world. India, however, chooses to remain on the list of countries where it isn’t; a list that includes Afghanistan, China, Eritrea, Iran, Iraq, Libya, Pakistan and Saudi Arabia.

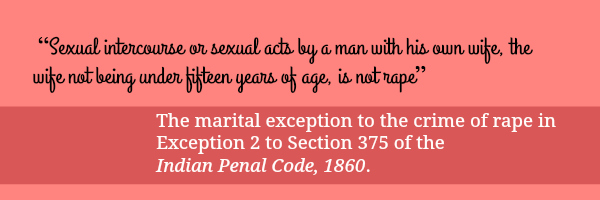

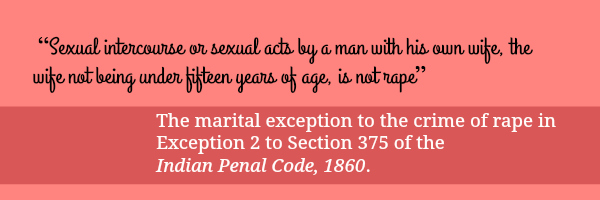

In the wake of the horrific events of December 16, 2012, the Justice J.S. Verma Committee reflected long and hard on how our criminal law system deals with various kinds of sexual violence perpetrated on women and children. Nearly six pages of its Report concentrated on the problem of marital rape. It recommended that the exception for marital rape be removed (Exception 2 to Section 375 of the Indian Penal Code, 1860 states that “Sexual intercourse or sexual acts by a man with his own wife, the wife not being under fifteen years of age, is not rape”), and that the law ought to specify that a marital relationship between the perpetrator and the victim cannot be used as a defence against rape and that it should not even be regarded as a mitigating factor justifying lower sentencing for rape.

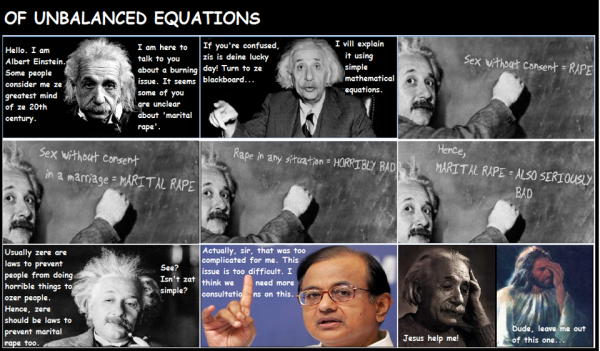

The ordinance that was drafted on the basis of the Report included many of its recommendations but left out some of the most important ones, perhaps chief among them the recommendation on marital rape. Defending the ordinance, Union Finance Minister P. Chidambaram said that issues like marital rape were difficult and that the government needed more consultations. This was, to put it mildly, perplexing. In modern times, the criminalisation of marital rape seems to be a very simple, logical, rational conclusion. In fact, one needs to perform several extraordinary feats of mental gymnastics to justify and legitimise the opposite. How is it that those who maintain that rape should attract the harshest punishment for the perpetrator suddenly find the act acceptable when a husband does it to a wife, as if a wedding is a Harry Potter-esque invisibility cloak that makes the crime disappear?

As a response to the government’s hedging on the issue, we posted the following comic on Facebook on February 9, 2013:

Now, I confess there are problems with this comic – it’s a little simplistic, and also Einstein might not have been the best choice to deliver this lesson as he was hardly the greatest husband in the world – but, the point was that it does not, or should not, take a genius to understand why the marital exception to rape should be removed.

A family that disrespects individual autonomy together…

And now, it seems the marital exception is one of those things the UPA and NDA governments agree upon. Well actually, while the former claimed that they were at least considering it, the latter seem to have ended the conversation altogether. Maneka Gandhi, the Minister for Women and Child Development has said, “It is considered that the concept of marital rape, as understood internationally, cannot be suitably applied in the Indian context due to various factors like level of education/illiteracy, poverty, myriad social customs and values, religious beliefs, mindset of the society to treat the marriage as a sacrament, etc.” This is a stunning departure from her position on the marital exception to rape just last year and the most puzzling argument I have ever heard about a legal issue. What does illiteracy or poverty have to do with amending a law that demonstrably causes physical and mental trauma to individuals? Did social customs and religious beliefs of some people stop the legislature from making laws against sati, child marriage, dowry and caste-based discrimination?

The “mindset of the society to treat the marriage as a sacrament” point is an old one. The claim is that marriage is a sacred bond between a man and a woman (only between a man and a woman), and that the state has no business interfering in the domestic affairs of a married couple. This argument is woefully flimsy. Laws on domestic violence and divorce would not exist if the state did not think legal intervention was necessary even in a marriage.

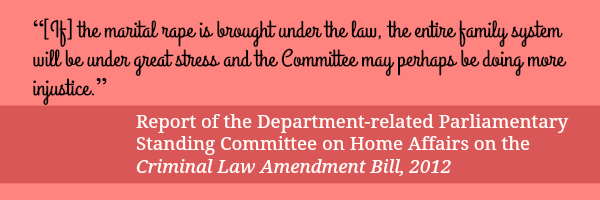

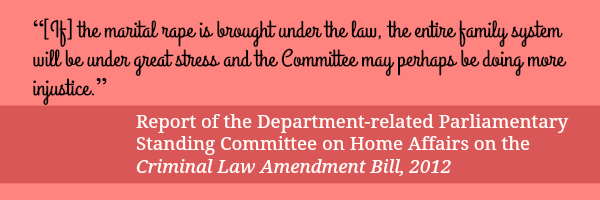

A similar argument was used in a report on the recommendations of the Justice Verma Committee prepared by the Department-Related Parliamentary Standing Committee on Home Affairs and presented in both houses in March, 2013. It stated that while some members had suggested that Section 375 of the Indian Penal Code should allow “some room for wife [sic] to take up the issue of marital rape”, that “no woman takes marriage so simple [sic] that she will just go and complain blindly” and that “consent in marriage cannot be consent forever”, several members “felt that the marital rape [sic] has the potential of destroying the institution of marriage.” The report went on to say that “In India, for ages, the family system has evolved and it is moving forward. Family is able to resolve the problems and there is also a provision under the law for cruelty against women. It was, therefore, felt that if the marital rape is brought under the law, the entire family system will be under great stress and the Committee may perhaps be doing more injustice.”

What this suggests is mind-bogglingly terrifying. It seems to assert that the foundation of an Indian family is not based on trust, love, equality, understanding, cooperation, mutual respect and interdependence. It is based on a skewed power structure where one partner gets to inflict violence on the body and mind of the other, where the success of the relationship depends on how much the partner with less power can endure. Imagine being punched in the stomach by your brother and then being told that you should just suck it up because the law says when your sibling hits you, it’s not assault. Now imagine that he beats you up whenever he pleases and you are told that this is not a crime being committed repeatedly on your body because surely, as a family, you can work things out. If you report him to the police, the family system in India will crumble. Surely, the preservation of the “Indian family” is more important than the physical and mental trauma being caused to you.

The Standing Committee consisted of 29 members at the time, none of whom had any specific experience or expertise in women’s issues. Only 3 of the members were women. One of them was Dr. Kakoli Ghosh Dastidar, a Trinamool leader who in December, 2012 had said that the gang rape of Suzette Jordan in Park Street, Kolkata “was not at all a rape case. It was a misunderstanding between the two parties involved between a lady and her client,” thus insinuating that Jordan was a sex worker. When the report was published, a dissenting note was appended to it, and among other things, it condemned the Standing Committee’s position on marital rape as unconstitutional and contrary to the Justice Verma Committee’s recommendations. The note was given by only two members of the Standing Committee: D. Raja and Prasanta Chatterjee, of the Communist Party of India and Communist Party of India (Marxist), respectively. No other member recorded dissent.

India’s relationship with its colonial era laws is simultaneously confounding and tragicomic. On the one hand we puff up our chests with pride when we think of our freedom struggle and victory over our colonial oppressors, and on the other hand we cling stubbornly and blindly to their archaic laws, which have no place in modern times – laws that even they have done away with. But what is truly depressing is that we undervalue women so much that we would rather grasp at half-baked fictions and outdated notions of family than address the real harm being done to real individuals in real time. We are only too happy to declare that our society is too primitive to accept modern ideas and then sacrifice the safety of women on the altar of our own apathy. Yes, laws are often only amended after there has been a change in social attitude towards the issue in question, but in India, we have also had a long history of enacting laws as instruments to bring about such social change. We can either embrace that history and move with the times or throw in our lot with a man who died four centuries ago and a belief that should have died with him.

(Sayak Dasgupta wanders around myLaw.net looking for things to do.)

Sir Matthew Hale, one of England’s greatest jurists, was a simple, humble, and fastidiously honest man. In fact, so unimpeachable was his character that, despite being a royalist who defended the opponents of the Commonwealth of England during the English Civil War, he was still appointed a justice of the common pleas by Oliver Cromwell when the Commonwealth came to power. When the Restoration happened, the King appointed him Chief Baron of the Exchequer, even though he had held office in the government of his mortal enemies. Hale, it is said, had no desire to receive the knighthood, so he literally had to be tricked into it (Lord Clarendon invited Hale to his house where the King was waiting to knight him on the spot).

Sir Matthew Hale, one of England’s greatest jurists, was a simple, humble, and fastidiously honest man. In fact, so unimpeachable was his character that, despite being a royalist who defended the opponents of the Commonwealth of England during the English Civil War, he was still appointed a justice of the common pleas by Oliver Cromwell when the Commonwealth came to power. When the Restoration happened, the King appointed him Chief Baron of the Exchequer, even though he had held office in the government of his mortal enemies. Hale, it is said, had no desire to receive the knighthood, so he literally had to be tricked into it (Lord Clarendon invited Hale to his house where the King was waiting to knight him on the spot).