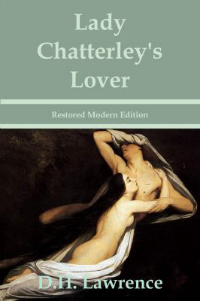

There was a sense of prophecy when D.H. Lawrence penned the first line to Lady Chatterley’s Lover, his novel about how, impervious to how it often ends in loss, we continue to seek romance. The words, “[o]urs is essentially a tragic age, so we refuse to take it tragically”, had a wider prescription. Little did Lawrence know that his book would inspire in India, the nebulous legal standards for obscenity that would become catastrophic for the liberty of authors, publishers, and readers.

There was a sense of prophecy when D.H. Lawrence penned the first line to Lady Chatterley’s Lover, his novel about how, impervious to how it often ends in loss, we continue to seek romance. The words, “[o]urs is essentially a tragic age, so we refuse to take it tragically”, had a wider prescription. Little did Lawrence know that his book would inspire in India, the nebulous legal standards for obscenity that would become catastrophic for the liberty of authors, publishers, and readers.

In 1964, acting on the prosecution of a bookseller for obscenity under Section 292 of the Indian Penal Code, 1860 (“IPC”) for the sale of this book, a three-judge bench of the Supreme Court of India adopted the “Hicklin test”. The Court stated in Ranjit Udeshi v. State of Maharashtra that, “the tendency of the matter charged as obscene must be to deprave and corrupt those, whose minds are open to such immoral influences and into whose hands a publication of the sort may fall, so far followed in India, is the right test.” Even today, FIRs are filed against authors while courts continue to deliberate the fuzzy standards for obscenity. Moreover, for each word they write, authors have to negotiate several other content-based offences.

The process of banning a book

Even though individual prosecutions for obscenity and other offences occur regularly, they do not, by themselves, result in the prohibition of the sale or distribution of a book. This power of forfeiture comes from Section 95 of the Code of Criminal Procedure, 1973 (“CrPC”), which allows a state government to prohibit a publication by a notification in the official gazette. In its the recent decision in State of Maharashtra v. S. Damodar, the Supreme Court, while overturning a ban on James Laine’s book on Shivaji, stated the ingredients of a valid notification prohibiting a publication.

Even though individual prosecutions for obscenity and other offences occur regularly, they do not, by themselves, result in the prohibition of the sale or distribution of a book. This power of forfeiture comes from Section 95 of the Code of Criminal Procedure, 1973 (“CrPC”), which allows a state government to prohibit a publication by a notification in the official gazette. In its the recent decision in State of Maharashtra v. S. Damodar, the Supreme Court, while overturning a ban on James Laine’s book on Shivaji, stated the ingredients of a valid notification prohibiting a publication.

The state government must first form an opinion that the matter constitutes an offence under one of Sections 124A (sedition), 153A (communalism), 153B (insults to religions), 292 (obscenity), or 295A (outraging religious feelings) of the IPC. Secondly, such an opinion should be published in the official gazette. Importantly, a police officer’s power under this process is not limited to the territorial limits of any state in which the ban has been issued. With the power to confiscate and prosecute publications made available throughout India therefore, even when a book banning notification is issued in Maharashtra, it is often pulled from sale from online bookstores and bookstores in other states.

A statutory opportunity to contest such a ban is provided in Section 96 of the CrPC itself. It allows appeals to the High Court of the state in which the notification for banning has been issued. Further, this right of appeal is not limited to the author or the publisher. Any other person may sue as well. Section 96 therefore, is one of the few provisions of law, which expressly recognises the right to read and the public injury from a ban. It is interesting to note that this provision in its original form can be traced to the Code of Criminal Procedure, 1889 and so ideologically, does not sprout from our constitutional jurisprudence.

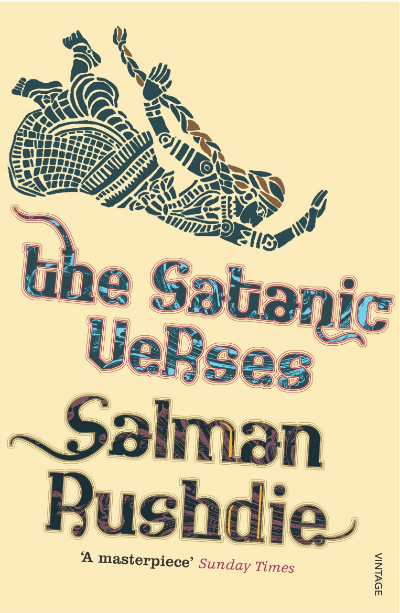

Since such a power to ban a publication is available only to the state government, the Union Government has made inventive use of the Customs Act, 1952 (“Customs Act”), most glaringly to prohibit the import of Salman Rushdie’s The Satanic Verses through a notification dated October 5, 1988 under Section 11 of the Customs Act. Rushdie is not alone. Many books on Kashmir and critical accounts of the assassination of Mahatma Gandhi and the Sino-Indian War remain banned by customs authorities.

Since such a power to ban a publication is available only to the state government, the Union Government has made inventive use of the Customs Act, 1952 (“Customs Act”), most glaringly to prohibit the import of Salman Rushdie’s The Satanic Verses through a notification dated October 5, 1988 under Section 11 of the Customs Act. Rushdie is not alone. Many books on Kashmir and critical accounts of the assassination of Mahatma Gandhi and the Sino-Indian War remain banned by customs authorities.

Private censorship

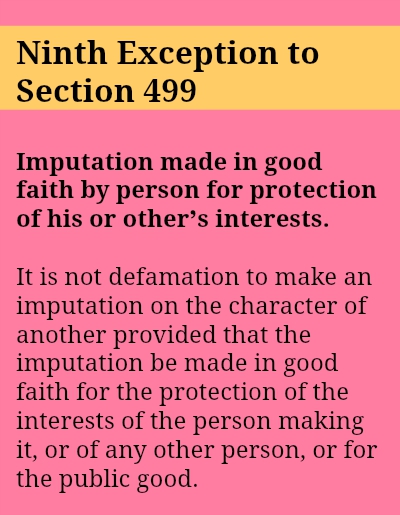

Though censorship of books by the state in the manner described above has decreased in frequency over the past few years, a worrying trend has emerged in which private persons have successfully caused the censorship of many books. Such censorship, either through a private compromise with the publisher or through a court injunction that is issued before the case is heard on evidence, is mostly a result of allegations of defamation. Defamation exists independently as a criminal offence and as a civil wrong.

Section 499 of the IPC defines the offence of defamation. People found guilty can be sentenced to imprisonment for up to two years. The civil wrong is based on common law and is derived from the judgments of courts and plaintiffs usually seek damages and a perpetual injunction against the defendant from publishing or distributing the work. In practice however, due to delays, criminal trials are itself a process in harassment for authors and publishers and civil suits are compromised after interim injunctions are liberally issued.

The most visible instance of a criminal trial resulting in a compromise for pulping a book is the case of Wendy Doniger’s The Hindus. The book was withdrawn pursuant to a compromise between its publisher Penguin and Dinanath Batra, a former general secretary of the education wing of the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh, who had instituted a complaint case under various offences against them. The author’s public statement to quell the criticism faced by the publisher blamed substantive offences in Indian law, specifically Section 295A of the IPC. Another recent instance is that of Bloomsbury withdrawing Jitender Bhargava’s The Descent of Air India under the terms of the settlement of the criminal defamation case instituted in a Mumbai court by Praful Patel, the former Union Minister for Civil Aviation.

The most visible instance of a criminal trial resulting in a compromise for pulping a book is the case of Wendy Doniger’s The Hindus. The book was withdrawn pursuant to a compromise between its publisher Penguin and Dinanath Batra, a former general secretary of the education wing of the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh, who had instituted a complaint case under various offences against them. The author’s public statement to quell the criticism faced by the publisher blamed substantive offences in Indian law, specifically Section 295A of the IPC. Another recent instance is that of Bloomsbury withdrawing Jitender Bhargava’s The Descent of Air India under the terms of the settlement of the criminal defamation case instituted in a Mumbai court by Praful Patel, the former Union Minister for Civil Aviation.

The position with respect to civil suits is not much better. It took five years for Kushwant Singh to have an interim inunction lifted from the Delhi High Court for a chapter he wrote about Maneka Gandhi which she alleged, was defamatory. Setting aside the interim injunction, the High Court rebuked the Single Judge’s order stating that its observations about the “high thinking, higher living and high learning of the author are  subjective moralistic observations.” Other recent court injunctions include ones issued by a district court in Silchar against a chapter in Siddharth Deb’s, The Beautiful and the Damned and against Tamal Bandyopadhyay’s Sahara: The Untold Story. One senses a pattern where it is easier to get an interim injunction and then coerce the author to drop a passage than for the author to appeal the injunction, persevere, and then publish the book in its entirety.

subjective moralistic observations.” Other recent court injunctions include ones issued by a district court in Silchar against a chapter in Siddharth Deb’s, The Beautiful and the Damned and against Tamal Bandyopadhyay’s Sahara: The Untold Story. One senses a pattern where it is easier to get an interim injunction and then coerce the author to drop a passage than for the author to appeal the injunction, persevere, and then publish the book in its entirety.

More often, one finds that even before a case is filed through the device of a legal notice to the publisher quoting exaggerated and anticipated damages, private parties successfully prevent publications. A recent attempt at this was made by Reliance Industries who sent a legal notice claiming a hundred crore rupees as damages from the author of Gas Wars, Paranjoy Thakurta. Distressingly, such bullying often finds success. Quite recently, Orient Blackswan withdrew Megha Kumar’s Communalism and Sexual Violence:  Ahmedabad Since 1969 following a legal notice sent by Dinanath Batra against another book in its catalogue! Following the receipt of the notice, the publisher commenced a review of its entire catalog, resulting in the withdrawal. Many blame the publishers, but most blame the laws which allow such offence. Though experienced litigators often term such actions as an abuse of law, many would ask, if the law permits such abuse, isn’t the law by itself abusive?

Ahmedabad Since 1969 following a legal notice sent by Dinanath Batra against another book in its catalogue! Following the receipt of the notice, the publisher commenced a review of its entire catalog, resulting in the withdrawal. Many blame the publishers, but most blame the laws which allow such offence. Though experienced litigators often term such actions as an abuse of law, many would ask, if the law permits such abuse, isn’t the law by itself abusive?

Liberalism through judgments?

In this raging debate, a popular opinion is that the higher judiciary has imparted a liberal reading of the law in favor of authors. This impression is only grounded in rhetoric for several reasons. Quite obviously, most authors and publishers have to wait for years and exhaust the process of appeals before they can approach the higher courts. Any such remedy therefore is an illusory one. Even when writ remedies or an accelerated appeals process is availed of, the approach of the High Courts and the Supreme Court has generally been conservative.

Most often, the higher judiciary examines irregularities either in the criminal procedure or in the banning notification alone. It helps that complainants do not reason the ingredients of the offence complained of and that banning notifications are passed without stating any grounds for the opinion. The examination does not go deeper and the higher courts generally prefer to remand the case for a trial by evidence or defer to the opinion of the state government. Even when such a process-based scrutiny is applied, courts do not hesitate to become censors by themselves.

Two of the latest book banning cases from the Supreme Court illustrates this point. In State of Maharashtra v. S. Damodar, the Court only looked at the ingredients of the banning notification issued by the state government, which made reference to a FIR registered under Section 153A. Since the Court had previously quashed the FIR, it set aside the banning notification. Prior to doing this, in an oral hearing, the Court made a suggestion to delete the alleged offensive passages to enable the state government to lift the ban on the book.

Two of the latest book banning cases from the Supreme Court illustrates this point. In State of Maharashtra v. S. Damodar, the Court only looked at the ingredients of the banning notification issued by the state government, which made reference to a FIR registered under Section 153A. Since the Court had previously quashed the FIR, it set aside the banning notification. Prior to doing this, in an oral hearing, the Court made a suggestion to delete the alleged offensive passages to enable the state government to lift the ban on the book.

The second instance is where the Supreme Court, in Sri Baragur Ramachandrappa v. State of Karnataka, upheld the notification banning Dharmakaarana, a Kannada novel by P.V. Narayana. In reaching its decision to uphold the banning notification, the Supreme Court cited additional “offensive” passages that were not cited in the banning notification. In a sense, it seemed that the Supreme Court was substituting its own reasons for the ban, going beyond the ones given by the state government. As with Damodar’s Case, the Court again asked the author to delete the offending passages.

Even otherwise, it remains beyond dispute that the underlying substantive law, in spite of attempts to limit its application by precedent, remains subjective. During such a subjective assessment, the content by itself is often examined, and the subjectivity in the law allows for tremendous discretion and inconsistency. A good illustration of this is the recent Supreme Court decision in Aveek Sarkar v. State of West Bengal, where a two-judge bench of the Supreme Court expressly stated that the Hicklin test is outdated and moved towards the more liberal “community standards test” as laid down by the United States Supreme Court in Miller v. California.

Though many would celebrate this shift in precedent, it should be greeted with cautious optimism. Since, the judgment in the Ranjit Udeshi Case was pronounced by a three-judge bench, the observations in Aveek Sarkar by a two-judge bench appear to be per incuriam. Secondly, there exists a vast gap between doctrinal liberalism and its practical application. For years at end, district courts will continue to apply the time honed Hicklin test. Finally, even substantively, the application in Aveek Sarkar is by a panel of judges who sit in the place of the jury and apply “community standards”. While this may often lead to outcomes that favour expression over censorship, it again inheres subjectivity in application. The purported high thresholds set by Aveek Sarkar, remain only in theory.

These cases demonstrate that the Supreme Court is often clumsy and lacks ideological consistency its free speech jurisprudence. In his personal essays explaining the motivations for the themes and styles that would offend many, D.H. Lawrence stated that he had set out to conquer taboos. In this, he failed in India. Sections of our society remain conservative and puritanical to the extent of being exclusionary against views that do not conform to their beliefs. Worse, the law allows their annoyance as an offence and their morality as legality. Close to a century since Lady Chatterley’s Lover was first written, we still remained tethered to Victorian virtues trapped in legal codes. It comes as some comfort that authors rarely care about law when they write, for they have “got to live, no matter how many skies have fallen”.

Apar Gupta is a partner at Advani & Co., and was recently named by Forbes India in its list of thirty Indians under thirty years of age for his work in media and technology law.

Two cases that the Supreme Court has been hearing during the last few weeks do not have anything to do with each other at first glance – the legality of the Aadhaar card scheme (“the Aadhaar case” – including Writ Petition (C) No 494 of 2012) and the constitutionality of the law of criminal defamation (the “criminal defamation case” – including Writ Petition (Crl) No 184 of 2014). Both are complex cases but my focus is on the contradiction about the right to privacy arising from the arguments made on behalf of the Union in both these cases.

Two cases that the Supreme Court has been hearing during the last few weeks do not have anything to do with each other at first glance – the legality of the Aadhaar card scheme (“the Aadhaar case” – including Writ Petition (C) No 494 of 2012) and the constitutionality of the law of criminal defamation (the “criminal defamation case” – including Writ Petition (Crl) No 184 of 2014). Both are complex cases but my focus is on the contradiction about the right to privacy arising from the arguments made on behalf of the Union in both these cases.