India’s constitution, crafted to serve as a roadmap for a nascent democracy, was born at a time when the horrors of the Second World War and the accompanying Jewish holocaust had given way to the drab and earnest socialism of post-war Britain’s labour government. The horrors of the Stalinist gulags were yet to be revealed and the socialistic belief that a man could, by society and by law, be compelled to love his neighbour, was yet to be shattered by Thatcherism. India itself had emerged bisected along communal lines, but was home to a huge population of minorities that had rejected the two-nation theory. Violence during Partition had cost more than a million lives. In an uncertain hour was born that tryst with destiny, and it needed an assembly of wise men to craft a constitution for a new republic where secularism and socialism were woven into the constitutional fabric.

India’s constitution, crafted to serve as a roadmap for a nascent democracy, was born at a time when the horrors of the Second World War and the accompanying Jewish holocaust had given way to the drab and earnest socialism of post-war Britain’s labour government. The horrors of the Stalinist gulags were yet to be revealed and the socialistic belief that a man could, by society and by law, be compelled to love his neighbour, was yet to be shattered by Thatcherism. India itself had emerged bisected along communal lines, but was home to a huge population of minorities that had rejected the two-nation theory. Violence during Partition had cost more than a million lives. In an uncertain hour was born that tryst with destiny, and it needed an assembly of wise men to craft a constitution for a new republic where secularism and socialism were woven into the constitutional fabric.

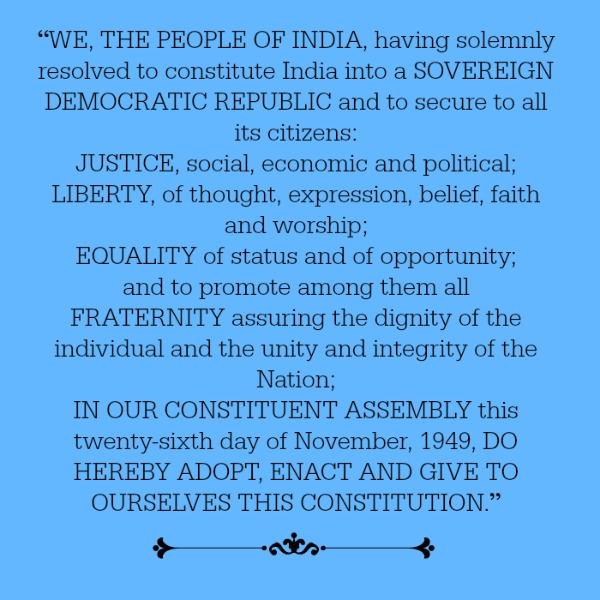

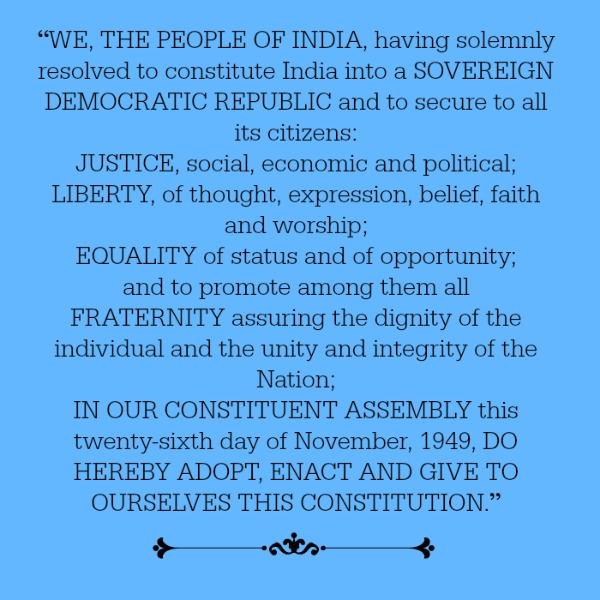

On November 26, 1949, the Constituent Assembly, after nearly two years of labour, built over the skeletal framework of the Government of India Act of 1935. It was fleshed out with fundamental rights, directive principles, and other provisions to produce a living and breathing constitution, among the world’s longest. The document now needed a face – a mission statement to tell posterity about the kind of republic into which the constitution makers hoped the nation would evolve to.

The original Preamble read:

When we carefully read and do not merely scan it, it is apparent that the Preamble makes no reference to God. Unlike the United States, which pledged to make “one nation under God”, the Constituent Assembly “solemnly affirmed” its resolve without seeking the munificence of any deity or supernatural power of any denomination. A solemn affirmation of the people’s resolve was sufficient to assure to its all its citizens “social, economic and political JUSTICE and EQUALITY of status and of opportunity”. A reader may well recognise in these phrases, a nascent republic intent on socialism. When the preamble further promised “LIBERTY, of thought, expression, belief, faith and worship”, it provided for the atheist, theist, and the agnostic alike. Secularism as a guiding principle was writ large.

In the Constituent Assembly, on November 15, 1949, B.R. Ambedkar, while replying to an amendment, said,

“Sir,…If you state in the Constitution that the social organisation of the State shall take a particular form, you are, in my judgment, taking away the liberty of the people to decide what should be the social organisation in which they wish to live. It is perfectly possible today, for the majority people to hold that the socialist organisation of society is better than the capitalist organisation of society. But it would be perfectly possible for thinking people to devise some other form of social organisation which might be better than the socialist organisation of today or of tomorrow. I do not see therefore why the Constitution should tie down the people to live in a particular form and not leave it to the people themselves to decide it for themselves. This is one reason why the amendment should be opposed.

“Sir,…If you state in the Constitution that the social organisation of the State shall take a particular form, you are, in my judgment, taking away the liberty of the people to decide what should be the social organisation in which they wish to live. It is perfectly possible today, for the majority people to hold that the socialist organisation of society is better than the capitalist organisation of society. But it would be perfectly possible for thinking people to devise some other form of social organisation which might be better than the socialist organisation of today or of tomorrow. I do not see therefore why the Constitution should tie down the people to live in a particular form and not leave it to the people themselves to decide it for themselves. This is one reason why the amendment should be opposed.

The second reason is that the amendment is purely superfluous. My Honourable friend, Prof. Shah, does not seem to have taken into account the fact that apart from the Fundamental Rights, which we have embodied in the Constitution, we have also introduced other sections which deal with directive principles of state policy. If my honourable friend were to read the Articles contained in Part IV, he will find that both the Legislature as well as the Executive have been placed by this Constitution under certain definite obligations as to the form of their policy. Now, to read only Article 31, which deals with this matter: It says:

“The State shall, in particular, direct its policy towards securing –

(i) that the citizens, men and women equally, have the right to an adequate means of livelihood;

(ii) that the ownership and control of the material resources of the community are so distributed as best to subserve the common good;

(iii) that the operation of the economic system does not result in the concentration of wealth and means of production to the common detriment;

(iv) that there is equal pay for equal work for both men and women;….”

There are some other items more or less in the same strain. What I would like to ask Professor Shah is this: If these directive principles to which I have drawn attention are not socialistic in their direction and in their content, I fail to understand what more socialism can be…”

It is thus certain that Ambedkar, while discussing the economic philosophy of the Constitution, felt that what was already implicit in the constitution, need not be reiterated. He took it for granted that the body of the constitution already had its guiding principles, including socialism and secularism, woven into the fabric.

It is wrong to think that it was only with the Forty-Second Amendment, which inserted the words “socialist” and “secular” into the Preamble, that these alien concepts were brought into the Constitution. The amendment only made explicit in the preamble that which was already implicit in the body. The sovereign democratic republic of India of November 26, 1949, did not on January 3, 1977, during the Emergency, morph into a secular socialist republic. Even today, merely because some government advertisements have chosen to stick to the original version of 1949, the Preamble and the Constitution have not ceased to be secular or socialist. Nor will the Constitution itself cease to be secular or socialist even if by an amendment these words are dropped again at a later date. Secularism and socialism are woven into the constitutional fabric and any effort to eradicate these principles will fall afoul of the basic structure doctrine, which is used to invalidate constitutional amendments.

Shanti Bhushan (left) with Prashant Bhushan and Atal Behari Vajpayee in 1984. Photo courtesy: Kartik Seth, an advocate practising at the Supreme Court of India.

After the Emergency, the Forty-fourth Amendment passed by the Janata government undid most of the damage of the Forty-second Amendment. Even this amendment however, chose to preserve the addition of secular and socialist to the Preamble. Shanti Bhushan was the Union Law Minister who piloted the amendment and among his colleagues in the Cabinet were L.K. Advani and A.B. Vajpayee.

Their inheritors today cannot presume to forget constitutional history. They cannot assume that constitutional values are just meaningless words to be redacted from a mere book. Secularism and socialism are inherent in the basic structure of the national book, and are beyond the power of transient parliamentary majorities to efface or abridge. “Insaan ko insaan se ho bhaichara” is inherent in the secular and socialist framework of rights and directive principles, which have given meaning to the Constitution all these years.

Sanjay Hegde is an advocate practicing at the Supreme Court of India.