Why did the Chief Justice of India have a “breakdown” about the impossible burden facing the judiciary? Is the judiciary doing nothing about the massive backlog of pending cases at the courts? Are the courts really that slow in India? What is the problem, anyway? Will appointing new judges fix the problem? There are no simple, straightforward answers (or questions) when it comes to judicial pendency in India, but here is a video in which we have tried to make the issue much clearer.

Tag: judicial reforms

As a fresh law graduate, Harish Narassappa went to court to be handed a file numbered 1 of 1956. He thought to himself that it must have been a mistake – it must be 1 of 1996, but no, the number was right. Such was the extent of delays in the judicial process, he learnt. In this post, we meet two lawyers who picked up their first legal instincts inside courts – Harish Narasappa and Amba Salelkar – both having taken law degrees at NLSIU, the former in the mid-nineties, the latter in the mid-2000s. They remind us of Ramanathan’s sustained engagement with the question of law and poverty in diverse theatres, but these two lawyers built institutional edifices in furtherance of their queries about law’s role in the social process.

Having completed two stints of corporate practice, in London and in Mumbai, Narasappa returned to his hometown of Bangalore in 2005 and rented a space where he would begin an office. At this point, his vision was to do policy-related work. Two of his friends, Siddharth Raja and Roopa Doraswamy, also alumni of the National Law School of India University, had also quit their jobs, and asked if they could use the space. Over time, this space emerged as a corporate law firm. Their emphasis was on cultivating a space where young lawyers would be recruited and nurtured, where there was gender equity, humane working hours, and so on. The firm, eventually named Samvad Partners, grew over time to have a presence in four Indian cities, but Narasappa’s earlier desire to engage in policy matters had remained unfulfilled.

He started Daksh India in 2006. An idea initially, it took a couple of years to be registered. As a defining question of Daksh, Narasappa and his colleagues were interested in testing the efficacy of ‘democratic institutions’.

“…lot of people do things which makes change visible – volunteer time for a school, give some computers. I wanted to intervene at an institutional level…”

In sheer numbers, India carries an arrogant epithet of the largest democracy, but it is a democracy where the citizen’s capacity is numbed in the five-year period between elections. Further, he may have some form of accountability from elected representatives, but he doesn’t have the same from bureaucrats or other government agencies who may affect his well-being. Often, there is no recourse or clarificatory procedure available unless there has been a violation of a legal right, for which he can go to the courts. He does not know what the stance of his MP or MLA is on important issues like the Lokpal Bill, how he is going to argue in the house, and what his representative’s performance in the house has been like.

Daksh and Narassapa designed a survey, which initially ran in Karnataka, but in the past two years, in other states such as Rajasthan and Bihar as well. The survey results were reflected in ‘scorecards’ for MLAs. Before the 2013 Karnataka assembly elections, leading Kannada newspapers carried their surveys. The representatives who had performed well on the scorecards were happy, those who hadn’t, claimed that the right criteria had not been taken into account. There was great support from people who said that they appreciated knowing these things as they went in to vote. Daksh’s intervention was to make the electoral process more effective by making crucial information available in the public domain, in local languages, for citizens to be able to exercise the franchise effectively. Daksh’s new intervention – the Rule of Law project – addresses the issue of judicial delay. With it, Narasappa attempts to strengthen the bridge between the two legs of his practice – in law and in public policy.

Amba Salelkar moved from a litigating career in a Mumbai criminal law firm to working in disability law and policy, when she quit her Mumbai criminal law career and moved to Chennai to join the Inclusive Planet Centre for Disability Law and Policy. Her work in this realm concerned large sections of the public who suffered physical disability themselves or were caregivers or associates of others who suffered disability, legislators, law implementers, non-legal NGOs, and disability professionals.

After the switch, she could no longer take for granted the literacy in legalese on the part of the large and diverse constituency who were now her colleagues and associates. The other thing she began to get used to was the slow and seemingly non-eventful nature of policy work, involving long hours of deskwork and academic research. Initially, Salelkar wasn’t particularly interested in disability issues. It was the conviction and energies of Rahul Cherian, another older alumnus of the National Law School of India University that drew her in. She started working with Cherian on a shadow report on mental health law in India, something that interested her as she had received treatment for mental health concerns in her own life.

“Rahul Cherian envisaged the Inclusive Planet Centre for Disability Law and Policy as an offshoot of sorts from discussions which were taking place on inclusiveplanet.com. The latter was a social networking website which was accessible for persons with disabilities, and it was through this that Rahul was exposed to the gap in policy and legislative interventions on behalf of persons with disabilities. Rahul was heavily involved in the “right to read” movement, which was seeking an exception to copyright law to allow for published material to be converted into accessible formats, and found that there was a lot more to be achieved when it came to advocacy under the United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities….”

After Cherian’s death in February 2013, she came to lead the organisation. Apart from work in the legislative domain, trying to influence bureaucrats and legislators, Salelkar’s advocacy operations take her to teaching disability law to a series of concerned groups. Her objective is to breathe life into a legal imagination of a person with disability as a citizen, a professional, a worker, a consumer, and a service-receiver. She attempts to equip people like caregivers with tools from the Constitution (like fundamental rights) that can be used to their benefit. For instance, understanding the right to equality and the vast jurisprudence under Article 21 (right to life) and other constitutional law principles including the tradition of courts having used international conventions as the Supreme Court did in the Vishaka judgment, can be used for strategic litigation.

“Some people are fascinated by the law….Some people are jaded. They say the law promised us so much, especially with the 1995 Act, and it never delivered… My job is give them a realistic perspectives on the things that a legal avenue can offer. I don’t want to give people too much hope….My job is to tell them you may be right, but it doesn’t mean you will get a judgment in your favour….”

Salelkar sees her role as having live intersections with other rights-based movements – especially, queer and feminist movements, recognising the absence of support within the legal and judicial system for a category of person that does not match the standardised legal imagination of the ‘normal’ person. Disturbing the ‘normal’ is at the core of her long journey within and without the law.

We will continue talking about Narasappa and Salelkar as we look at their institutional energies in a larger ecosystem of policy reform.

(Atreyee Majumder is an anthropologist. She teaches at the School of Development, Azim Premji University.)

Of all the categories of persons incarcerated in prisons, the worst are the stories of undertrial prisoners. In the widest sense, undertrials are people who have not been proven guilty, but whose innocence is yet to established. The history of the prison system is rife with tales of undertrials who have spent years and years in jail for petty crimes, usually because they are unable to pay bail amounts, or worse, because they have no access to the justice system. This situation has not gone unnoticed. In September 2014, the Supreme Court directed the release of undertrial prisoners who have spent half of the maximum sentence prescribed for the offences they are alleged to have committed.

Of all the categories of persons incarcerated in prisons, the worst are the stories of undertrial prisoners. In the widest sense, undertrials are people who have not been proven guilty, but whose innocence is yet to established. The history of the prison system is rife with tales of undertrials who have spent years and years in jail for petty crimes, usually because they are unable to pay bail amounts, or worse, because they have no access to the justice system. This situation has not gone unnoticed. In September 2014, the Supreme Court directed the release of undertrial prisoners who have spent half of the maximum sentence prescribed for the offences they are alleged to have committed.

This is not the first time that undertrials have been the focus of judicial attention, but as advocate Vrinda Bhandari pointed out, while many deeper problems remain unaddressed, releasing undertrials is only a short-term solution. The condition of the other participants in the criminal justice system (police, prosecutors, judges, and prison administrators) is a significant problem in itself, as these professions tend to be “overworked, understaffed and underpaid”.

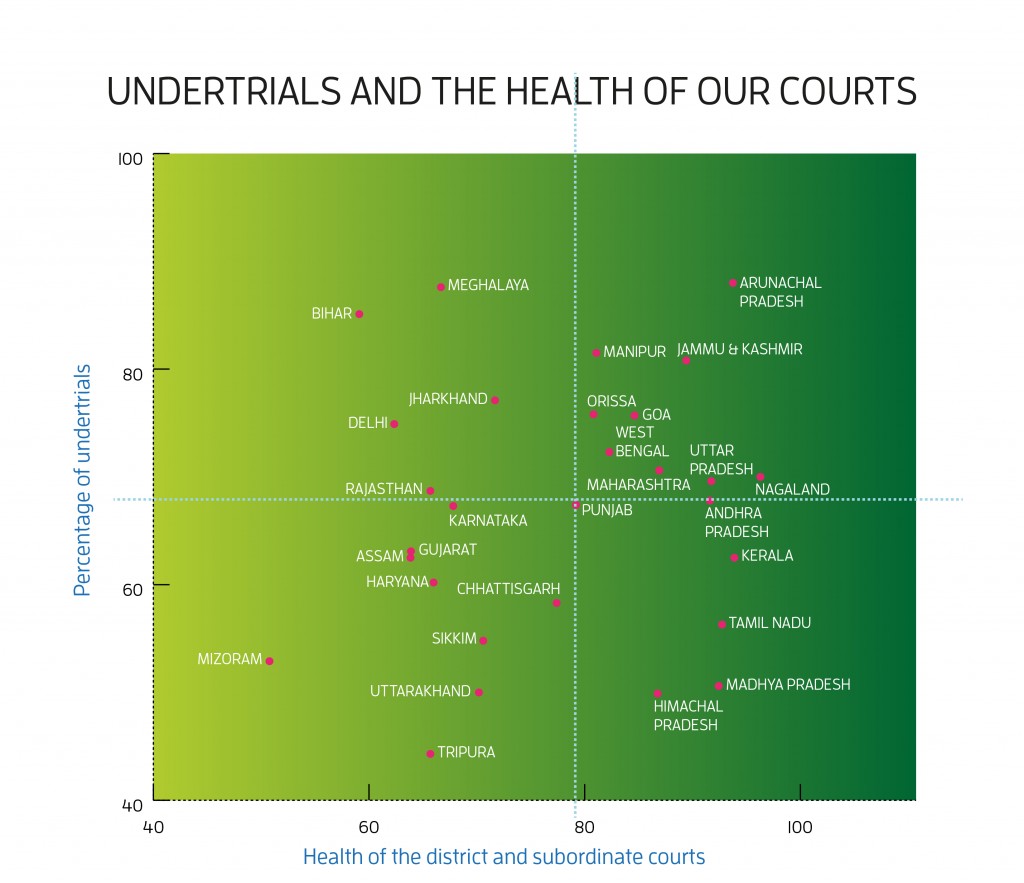

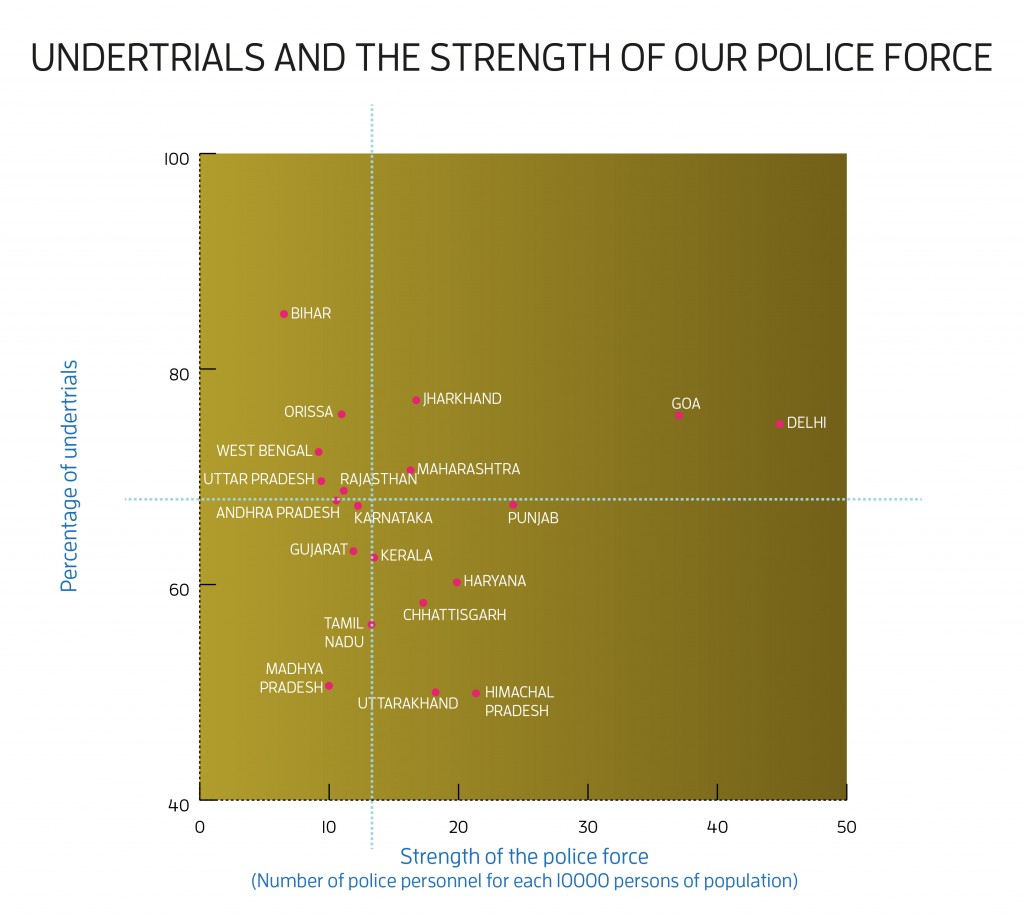

Some of the richest data available for analysing questions of law and policy in India relates to prisons and prisoners, through the National Crime Records Bureau, and its annual Prison Statistics India, the latest edition of which was published in October 2014. Combined with other data available from different sources, many interesting correlations can be drawn, with the usual caveats about data quality and the fact that mere correlation does not imply causation. The note focuses on state-wise undertrial populations, taking into consideration that several relevant issues are under the control of individual states, notably the police and prisons. The lack of access to the justice system and the inability to post bail suggests it might be interesting to examine two sets of intersections, between undertrial populations and first, the criminal justice system, and second, development indicators in states. Each scatterplot drawing below plots the undertrial population on the vertical axis against the other indicator on the horizontal axis. The dotted lines indicate the median values (the value in the middle of the dataset) of each indicator and they divide the plot into four quadrants.

Undertrials and the criminal justice system

As proxies for the criminal justice system, two parameters were looked at. First, the note examined the health of district and subordinate courts, based on data from Court News (Q4, 2013). This was derived as a measure of the working strength of the courts relative to the sanctioned strength of the courts, to arrive at a percentage of how “healthy” the courts were. The hypothesis was that states with more “healthy” court systems, that is, states where district and subordinate courts were working closer to their sanctioned strength, were also the states that had lower undertrials as a percentage of all prisoners. The relationship, as the image shows, is indistinct, but might become significant if the data are studied in greater detail (which this note does not attempt). Illustratively, if health of courts and undertrial populations for each state are studied over a longer period of time, it might be possible to show individual trendlines for each state, and test for inverse trends between the indicators.

Second, the note examined the police force per 10,000 people in various states, based on data for 2011, from data.gov.in, and the population census. The police force was taken as a measure of the total armed and civilian police force in states relative to the population of the states. The analysis discounted for outliers such as states in the north-east and Jammu & Kashmir, given their special situation regarding police and law enforcement. However, there did not appear to be any correlation between the strength of the police force, and the percentage of undertrial prisoners.

A better proxy for the criminal enforcement and prosecution system might have been the number of public prosecutors in various states. Unfortunately, the central government does not maintain any data as regards the number of public prosecutors working in various courts in various states.

Undertrials and development

The fate of undertrials is often attributed to their inability to understand their rights or their inability to post the bail amounts that might otherwise let them out of prison. As proxies for these, two indicators were looked at. First, the percentage of undertrials in prisons was compared with literacy rates in various states, based on data from the 2011 census. It appears that states that are relatively more literate also tend to be states that have a fewer number of undertrials in prison.

Second, the percentage of undertrials was compared with the tele-density of wireless connections across several areas in India, based on regulatory data, which was taken as a proxy for income. (Tele-density, or telephone density, means the number of telephone connections for every hundred people in an area.) Here, too, it appears that states with higher wireless tele-density tend to have a fewer percentage of undertrials in prison.

The degree of civilisation in a society, Dostoevsky is believed to have written, can be judged by entering its prisons. Could it be that society, too, has something to tell us about the prisons we create?

(Sumathi Chandrashekaran is a lawyer working in the area of public policy.)

Tribunals are notorious for having advocates on both sides of the fence in discussions on judicial remedies in India. Defendants of India’s tribunals argue that they offer an alternative forum for addressing subject-specific disputes and allow the parties to a dispute to move away from conventional courts and their accompanying problems. The subject-specific jurisdiction of tribunals, theoretically, requires them to be staffed by experts in those subjects, who are expected to understand better, the technical aspects of such disputes. And, because no standards have been set for their functioning, tribunals have the freedom to define their administrative processes and requirements (which, the argument goes, makes them superior to conventional courts).

Tribunals are notorious for having advocates on both sides of the fence in discussions on judicial remedies in India. Defendants of India’s tribunals argue that they offer an alternative forum for addressing subject-specific disputes and allow the parties to a dispute to move away from conventional courts and their accompanying problems. The subject-specific jurisdiction of tribunals, theoretically, requires them to be staffed by experts in those subjects, who are expected to understand better, the technical aspects of such disputes. And, because no standards have been set for their functioning, tribunals have the freedom to define their administrative processes and requirements (which, the argument goes, makes them superior to conventional courts).

The opposition to tribunals usually picks on these very features. They argue that tribunal structures in India are anything but standardised. With differences in compositions, eligibility requirements for members, procedures, and reporting standards, their performance and accountability is difficult to monitor. Further, subject-specific experts may not have enough of an understanding of the law.

The legal position of tribunals in the edifice of Indian democracy also remains unresolved. In the form that many of them operate today, tribunals in India perform functions that are inherently and integrally judicial in nature. But they continue to be staffed by bureaucrats who have no judicial experience or qualifications, and offer judicial remedies after following non-judicial processes. The question that is often asked is, are tribunals a part of the executive or the judiciary? For the purpose of public administration, are they to be regarded as quasi-judicial bodies, or administrative bodies? This issue reemerges every few years, phoenix-like, as it did in the September 2014 decision of the Supreme Court, which, following a rich jurisprudential history that includes Sampath Kumar and Chandra Kumar, held the National Tax Tribunal unconstitutional.

Legality apart, there are also questions about whether tribunals have met their specific objectives, that is, avoiding the problems faced by traditional courts such as long delays, high pendency, and the lack of specialised knowledge. To answer this, we need to explore the little that we know about tribunals in India.

Poor data

Firstly, the data about tribunals is sketchy, because they operate under different ministries that have no standardised processes for gathering information about them. The annual reports of various ministries are usually the best source of information. These reports, though, do not provide information in the same format. Where tribunals are split between the Centre and states, data collection is in complete disarray, and often, entirely absent. Indeed, for many large tribunals that have been functioning for several years, there is no authoritative information available at all. This is the case with the Motor Accident Claims Tribunals, which works under various states and union territories. The Ministry of Road Transport and Highways has admitted that there is no centralised repository of cases pending for disposal in such tribunals.

Unclear classification

Secondly, the system of classification of tribunals is unclear. For instance, we know that there were 62 tribunals in India as of May 2013, according to the Ministry of Law and Justice, but we know little else. The definition of tribunals that the ministry used to arrive at this number is unclear. Is it an administrative body exercising quasi-judicial functions, like the Securities and Exchange Board of India? Is it an adjudicatory body outside the control of the administrative department, exercising judgement like a third party arbiter? Or is it an administrative tribunal formed under the Constitution of India? This problem of classification comes into sharp focus when the legislature shows an increasing but irrational proclivity to create tribunals, as it did with the National Company Law Tribunal and its appellate tribunal in 2002, the Intellectual Property Appellate Board in 2003, and soon perhaps, a tribunal for addressing disputes in the infrastructure sector. Arvind Datar, who has spearheaded a series of constitutional challenges against tribunalisation in India, has argued that tribunals have become a “tragic obsession” for us.

Failed objectives

The third issue relates to whether tribunals achieve the objective they have been established for. At two large tribunals for which data is relatively more accessible – the Central Administrative Tribunal (“CAT”) and the Debt Recovery Tribunals (“DRTs”), the number of pending cases (note that different bodies may calculate it differently) has been, generally, on an upward march over the past few years.

Further, if we make simplistic calculations about the workload for various benches of the CAT and the DRTs, the number of pending cases that each bench of the two tribunals has to hear is also on the rise (for the CAT, this number has been taken to be 17, and for the DRTs, 33). The workload at the CAT is already more than the workload of judges in subordinate courts, and the DRTs are also nearing that number.

Evidently, these tribunals have failed to address the one major problem for which disputes were originally taken out of the mainstream system of judicial remedies, that is, to offer speedy disposal of disputes.

The limited data that is available shows that the tribunal “system”, if it can be called that, has not met its objectives. An increasing number of appeals to the Supreme Court against the decisions of tribunals indicate that disputing parties remain unsatisfied with their solutions. Quick-fixes, such as the creation of additional benches, as in the case of CESTAT in 2013, are not the answer. But a true assessment of the health of tribunals in India remains impossible without proper and complete information. Data collection needs to improve. The legislative mandates of tribunals and tribunal-like bodies need to be reassessed. Their functioning and their processes need to be standardised. Until then, any analysis of tribunals in India will remain in the realm of speculation.

(Sumathi Chandrashekaran is a lawyer working in the area of public policy.)

Lawmaking is at the heart of the democratic process. The number, the types, and the quality of laws made each year are significant indicators of the health of a democracy. A very large number of laws passed in a year, for instance, draw attention to the standard of parliamentary or legislative debate. An excessively detailed law on a simple subject, or a terse law on a complex subject, brings to focus, the question of delegation of powers. Too many amending laws demand an examination of the quality of the original parent legislations.

Lawmaking is at the heart of the democratic process. The number, the types, and the quality of laws made each year are significant indicators of the health of a democracy. A very large number of laws passed in a year, for instance, draw attention to the standard of parliamentary or legislative debate. An excessively detailed law on a simple subject, or a terse law on a complex subject, brings to focus, the question of delegation of powers. Too many amending laws demand an examination of the quality of the original parent legislations.

One feature of lawmaking that is only occasionally a subject of public debate in India is the effect of new laws. Studying the impact of new laws, also known as judicial impact assessment, involves estimating the additional case-load, expenditure, and other burdens that such laws are likely to impose on the judicial system.

Bills and financial memoranda

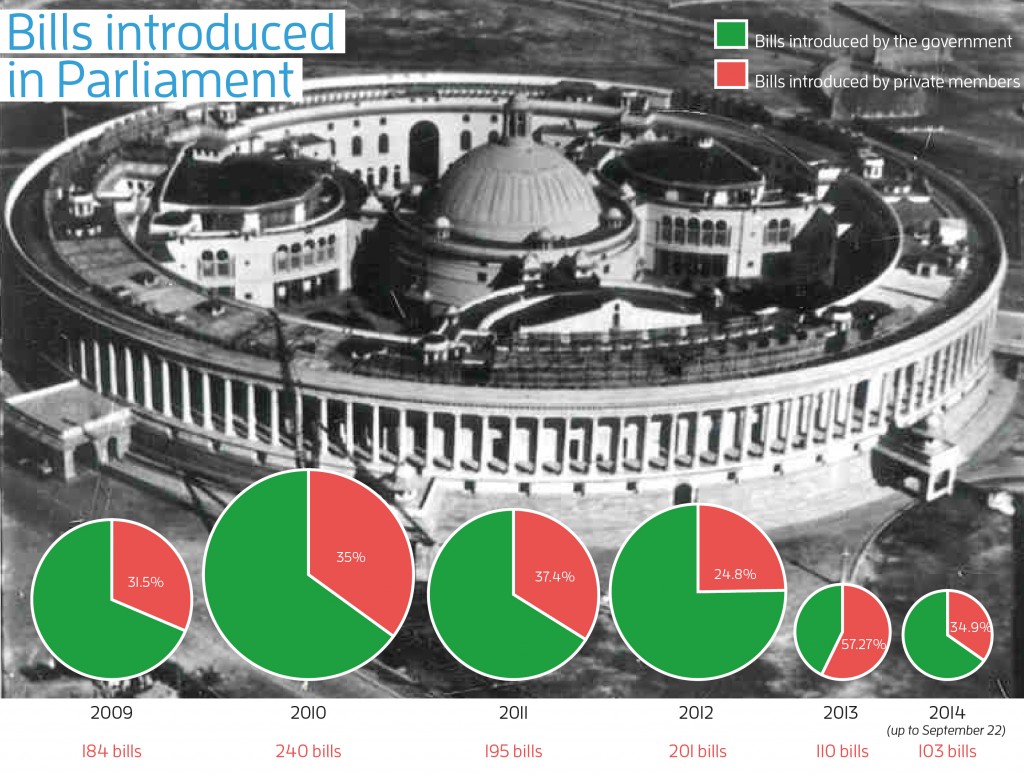

A large number of bills are introduced by the Parliament as well as the state legislatures every year. Between 2009 and 2014, an average of 172 bills were introduced in both houses of Parliament every year. Among these, the government alone introduced an average of about 60.

Not all these bills get passed, of course. Most (and practically all private member bills) remain pending. Nevertheless, these numbers indicate the enthusiasm with which legislators at the centre participate in the lawmaking process.

Bills tabled in Parliament are expected to be accompanied by three documents – a financial memorandum, a statement of objects and reasons, and a memorandum regarding the delegation of legislative powers. Under the Rules of Procedure and Conduct of Business in the Lok Sabha, financial memoranda are required to “invite particular attention to the clauses involving expenditure”, and provide “an estimate of the recurring and non-recurring expenditure” if the Bill is passed into law. In practice, however, these financial memoranda serve only as token appendices, providing little insight into the true implications on the exchequer, and no information on the effects on the populace. In effect, there is very little effort by the legislature to foresee the effect of laws they pass on the court system.

Burdensome legal provisions

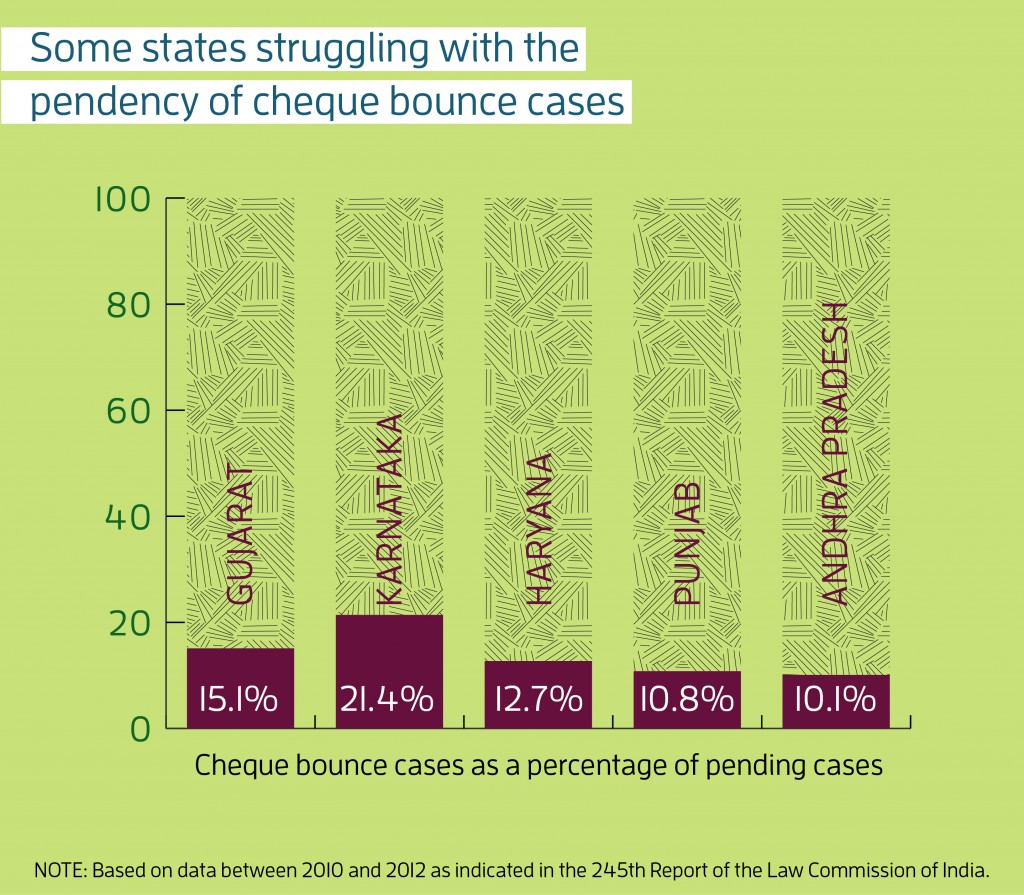

A frequently-cited example of a burdensome legal provision is the law on dishonoured cheques. A 2014 report of the Law Commission of India highlighted the disproportionate number of “cheque bounce” cases under Section 138 of the Negotiable Instruments Act, 1938 pending before Indian courts between 2010 and 2012. Acknowledging that the data was error prone due to incorrect reporting, it estimated that an average of about 7.8% of cases pending before various high courts in the country during this period was due to the law on negotiable instruments.

The “avalanche of litigation” invited by Section 138, introduced in its present form by way of an amending act in 1988, was the subject of a Madras High Court decision in 2008, which observed, “Had a judicial impact assessment been made … regarding the litigation this enactment would generate and the consequent financial impact on the State, we do not know if the result would have been in favour of enacting S. 138.”

Task force on judicial impact assessment

The effect of new laws became a subject matter of discussion in a 2005 case before the Supreme Court, Salem Advocate Bar Association v. Union of India, where a report submitted to the Court suggested a radical change to the nature of financial memoranda accompanying bills. The report studied amendments to the Code of Civil Procedure and said:

“Further, there must be ‘judicial impact assessment’, as done in the United States, whenever any legislation is introduced either in Parliament or in the State Legislatures. The financial memorandum attached to each Bill must estimate not only the budgetary requirement of other staff but also the budgetary requirement for meeting the expenses of the additional cases that may arise out of the new Bill when it is passed by the legislature. The said budget must mention the number of civil and criminal cases likely to be generated by the new Act, how many Courts are necessary, how many Judges and staff are necessary and what is the infrastructure necessary.”

The report spawned a larger discussion on judicial impact assessment in India, and was followed by a full-blown Task Force on Judicial Impact Assessment, which submitted its two-volume report (see here and here) in 2008. The task force said that judicial impact assessments must be carried out scientifically to estimate the additional case-load that any new legislation (introduced in Parliament as well as state legislatures) would place on courts. It also recommended that the cost of adjudicating such cases must be estimated and adequate budgetary provisions must be made accordingly. The task force further proposed an elaborate institutional structure to project such estimates, in the form of “judicial impact offices” located all over the country, modelling it on similar arrangements in the United States. Critically, in the proposed model, the role of the judicial impact offices included a continuous assessment of the impact of laws, including by way of post-facto verification of the original estimates, once the law was passed, to understand whether the projections were exaggerated or understated.

Judicial impact assessment has its detractors, such as G Mohan Gopal. He has argued that such assessments are “a blunt, ineffective and unnecessary instrument” for two reasons: first, reliable estimates of future litigation are impossible to obtain in India, where even basic court statistics are unavailable; and second, the recognition and creation of rights should not be linked to the existence or creation of judicial system capacity. He has suggested, instead, conducting “judicial use assessments”, which could measure if people were actually using courts to enforce their rights. Arguably, judicial use assessments have already been factored in by the mechanism proposed by the 2008 task force, through the verification of data relating to the impact of new laws, after they come into existence.

Judicial impact assessments continue to bear meaning for a country facing compound problems of high pendency and understaffed courts, besides fundamental concerns of legal literacy and access to justice. Unreliability of data remains a key concern, but it is very likely that data quality will improve with subsequent iterations. Such assessments offer at least one indicator of the impact of lawmaking, which has otherwise remained a black hole for statisticians and policymakers.

(Sumathi Chandrashekaran is a lawyer working in the area of public policy.)