Courts in India are faced with a huge backlog of cases, leaving parties embroiled in legal battles for years, often decades, at a stretch. Many factors contribute to this problem, including procedural inefficiencies, new laws passed without any litigation impact assessment, and poor court and case management systems.

Courts in India are faced with a huge backlog of cases, leaving parties embroiled in legal battles for years, often decades, at a stretch. Many factors contribute to this problem, including procedural inefficiencies, new laws passed without any litigation impact assessment, and poor court and case management systems.

One reason however, comes to mind before any of these other reasons – the apparent inadequacy of the present judicial workforce to handle the large numbers of pending cases. While we can use the available data on the backlog of cases to estimate the number of cases that each judge would have to handle if this backlog were to be cleared in the current year, (see the first figure below) it is crucial to highlight the limitations of the available data.

We don’t really know the magnitude of the problem

Without a uniform system for indexing and categorising cases, different states have devised their own methods for recording data. As the Law Commission of India observed in July this year, some states count each interlocutory application as a separate case while others do not. Similarly, while some states exclude data on traffic and motor challan cases, most others do not. There is therefore, doubt about the accuracy of pendency figures.

An incredible number of cases pending before each judge

Working within these limitations, we can see that the number of cases pending for each judge is staggeringly high. High court judges, whose potential workload is over three times that of their counterparts in the Supreme Court and at the subordinate courts, seem to be in the worst position.

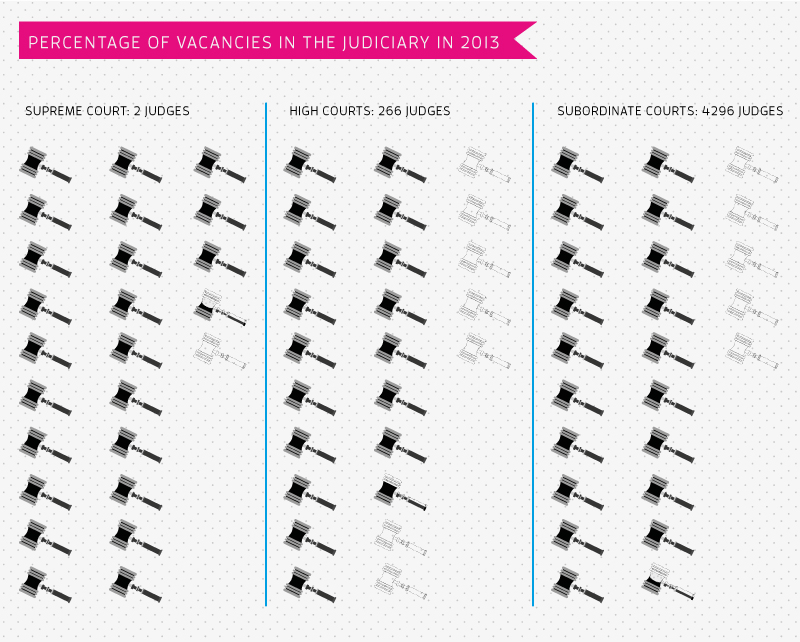

Many posts lie vacant

These numbers are based on the number of judges who are actually working, and not the sanctioned strength, which is the number of judges that are, on paper, expected to be in office. These two figures often tend to vary significantly. For example, at the end of 2013, 29 per cent of the posts in the High Courts and 22 per cent of the posts in subordinate courts were lying vacant.

On the bright side, the numbers show a steady increase in the sanctioned strength of judges over the years, particularly in subordinate courts, where it has gone up by over 30 per cent in the last eight years.

Who is responsible for filling these vacancies?

Recent debate surrounding the National Judicial Appointments Commission (“NJAC”) has focused extensively on appointments to the higher judiciary, that is, the Supreme Court and the High Courts. At present, because of the Supreme Court’s interpretation of Articles 124 and 217 of the Constitution, it is the judiciary that plays a decisive role in such appointments.

The proposed constitutional amendment and NJAC law will change this, creating NJAC as a permanent body to recommend appointments to the President. There will also be a timeline within which the central government has to inform the NJAC of imminent vacancies, though there is no such timeline timeline for the NJAC to complete its selection and make recommendations to the President.

The Governor appoints judges and judicial officers for subordinate courts in consultation with the High Court. The State Public Service Commission also has to be consulted for judicial officers below the rank of district judges. Rules made by different states provide for the actual recruitment process – whether through promotion or competitive examination.

The Governor appoints judges and judicial officers for subordinate courts in consultation with the High Court. The State Public Service Commission also has to be consulted for judicial officers below the rank of district judges. Rules made by different states provide for the actual recruitment process – whether through promotion or competitive examination.

In 2006, the Supreme Court in Malik Mazhar Sultan identified unfilled vacancies as a key reason for the pendency problem and directed states and High Courts to evolve a fixed schedule to fill vacancies in subordinate courts. After that, the Supreme Court itself devised a detailed time schedule for the states. The High Courts were asked to oversee this process, which included timelines for the determination of vacancies, issuing advertisements, conducting examinations and interviews, declaring results, and issuing final appointment orders. Seven years on, the Supreme Court is still struggling to ensure compliance with those directions.

How many judges do we need?

In 1987, the Law Commission recommended that there should be at least 50 judges for every million Indians. For today’s population of 1200 million therefore, India would need about 60,000 judges, that is, triple the current number of sanctioned judges.

In July this year, the Law Commission changed its opinion about the judge-population ratio, observing that it was not based on any objective criteria and that it did not capture state-specific needs. Instead, it proposed calculating the additional number of judges required to deal with the backlog of cases by using the current rate at which judges dispose of cases. By any reasonable metric however, the current sanctioned strength is far less than what is required.

Any real solution to these problems requires effective cooperation between the judiciary and the central and state governments. The judiciary should urgently take the initiative in filling vacancies and the government should create additional courts and extend infrastructure support to them.

(Sumathi Chandrashekaran and Smriti Parsheera are lawyers working in the area of public policy.)

(Images by Rachit Gupta.)