As a fresh law graduate, Harish Narassappa went to court to be handed a file numbered 1 of 1956. He thought to himself that it must have been a mistake – it must be 1 of 1996, but no, the number was right. Such was the extent of delays in the judicial process, he learnt. In this post, we meet two lawyers who picked up their first legal instincts inside courts – Harish Narasappa and Amba Salelkar – both having taken law degrees at NLSIU, the former in the mid-nineties, the latter in the mid-2000s. They remind us of Ramanathan’s sustained engagement with the question of law and poverty in diverse theatres, but these two lawyers built institutional edifices in furtherance of their queries about law’s role in the social process.

Having completed two stints of corporate practice, in London and in Mumbai, Narasappa returned to his hometown of Bangalore in 2005 and rented a space where he would begin an office. At this point, his vision was to do policy-related work. Two of his friends, Siddharth Raja and Roopa Doraswamy, also alumni of the National Law School of India University, had also quit their jobs, and asked if they could use the space. Over time, this space emerged as a corporate law firm. Their emphasis was on cultivating a space where young lawyers would be recruited and nurtured, where there was gender equity, humane working hours, and so on. The firm, eventually named Samvad Partners, grew over time to have a presence in four Indian cities, but Narasappa’s earlier desire to engage in policy matters had remained unfulfilled.

He started Daksh India in 2006. An idea initially, it took a couple of years to be registered. As a defining question of Daksh, Narasappa and his colleagues were interested in testing the efficacy of ‘democratic institutions’.

“…lot of people do things which makes change visible – volunteer time for a school, give some computers. I wanted to intervene at an institutional level…”

In sheer numbers, India carries an arrogant epithet of the largest democracy, but it is a democracy where the citizen’s capacity is numbed in the five-year period between elections. Further, he may have some form of accountability from elected representatives, but he doesn’t have the same from bureaucrats or other government agencies who may affect his well-being. Often, there is no recourse or clarificatory procedure available unless there has been a violation of a legal right, for which he can go to the courts. He does not know what the stance of his MP or MLA is on important issues like the Lokpal Bill, how he is going to argue in the house, and what his representative’s performance in the house has been like.

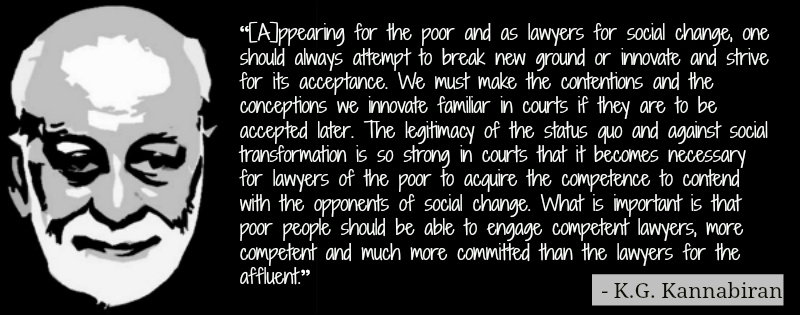

Harish Narasappa

Daksh and Narassapa designed a survey, which initially ran in Karnataka, but in the past two years, in other states such as Rajasthan and Bihar as well. The survey results were reflected in ‘scorecards’ for MLAs. Before the 2013 Karnataka assembly elections, leading Kannada newspapers carried their surveys. The representatives who had performed well on the scorecards were happy, those who hadn’t, claimed that the right criteria had not been taken into account. There was great support from people who said that they appreciated knowing these things as they went in to vote. Daksh’s intervention was to make the electoral process more effective by making crucial information available in the public domain, in local languages, for citizens to be able to exercise the franchise effectively. Daksh’s new intervention – the Rule of Law project – addresses the issue of judicial delay. With it, Narasappa attempts to strengthen the bridge between the two legs of his practice – in law and in public policy.

Amba Salelkar moved from a litigating career in a Mumbai criminal law firm to working in disability law and policy, when she quit her Mumbai criminal law career and moved to Chennai to join the Inclusive Planet Centre for Disability Law and Policy. Her work in this realm concerned large sections of the public who suffered physical disability themselves or were caregivers or associates of others who suffered disability, legislators, law implementers, non-legal NGOs, and disability professionals.

After the switch, she could no longer take for granted the literacy in legalese on the part of the large and diverse constituency who were now her colleagues and associates. The other thing she began to get used to was the slow and seemingly non-eventful nature of policy work, involving long hours of deskwork and academic research. Initially, Salelkar wasn’t particularly interested in disability issues. It was the conviction and energies of Rahul Cherian, another older alumnus of the National Law School of India University that drew her in. She started working with Cherian on a shadow report on mental health law in India, something that interested her as she had received treatment for mental health concerns in her own life.

Amba Salelkar

“Rahul Cherian envisaged the Inclusive Planet Centre for Disability Law and Policy as an offshoot of sorts from discussions which were taking place on inclusiveplanet.com. The latter was a social networking website which was accessible for persons with disabilities, and it was through this that Rahul was exposed to the gap in policy and legislative interventions on behalf of persons with disabilities. Rahul was heavily involved in the “right to read” movement, which was seeking an exception to copyright law to allow for published material to be converted into accessible formats, and found that there was a lot more to be achieved when it came to advocacy under the United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities….”

After Cherian’s death in February 2013, she came to lead the organisation. Apart from work in the legislative domain, trying to influence bureaucrats and legislators, Salelkar’s advocacy operations take her to teaching disability law to a series of concerned groups. Her objective is to breathe life into a legal imagination of a person with disability as a citizen, a professional, a worker, a consumer, and a service-receiver. She attempts to equip people like caregivers with tools from the Constitution (like fundamental rights) that can be used to their benefit. For instance, understanding the right to equality and the vast jurisprudence under Article 21 (right to life) and other constitutional law principles including the tradition of courts having used international conventions as the Supreme Court did in the Vishaka judgment, can be used for strategic litigation.

“Some people are fascinated by the law….Some people are jaded. They say the law promised us so much, especially with the 1995 Act, and it never delivered… My job is give them a realistic perspectives on the things that a legal avenue can offer. I don’t want to give people too much hope….My job is to tell them you may be right, but it doesn’t mean you will get a judgment in your favour….”

Salelkar sees her role as having live intersections with other rights-based movements – especially, queer and feminist movements, recognising the absence of support within the legal and judicial system for a category of person that does not match the standardised legal imagination of the ‘normal’ person. Disturbing the ‘normal’ is at the core of her long journey within and without the law.

We will continue talking about Narasappa and Salelkar as we look at their institutional energies in a larger ecosystem of policy reform.

(Atreyee Majumder is an anthropologist. She teaches at the School of Development, Azim Premji University.)