Today, one day after World Human Rights Day, India’s most progressive and respected institution has stained its proud record of protecting and advancing citizens’ rights — perhaps indelibly.

In 2009, the Delhi High Court in an inspired verdict, that decriminalised homosexuality, had said:

“If there is one constitutional tenet that can be said to be underlying theme of the Indian Constitution, it is that of ‘inclusiveness’. This Court believes that Indian Constitution reflects this value deeply ingrained in Indian society, nurtured over several generations. The inclusiveness that Indian society traditionally displayed, literally in every aspect of life, is manifest in recognising a role in society for everyone. Those perceived by the majority as ‘deviants’ or ‘different’ are not on that score excluded or ostracised.

Where society can display inclusiveness and understanding, such persons can be assured of a life of dignity and non-discrimination. This was the ‘spirit behind the Resolution’ of which Nehru spoke so passionately. In our view, Indian Constitutional law does not permit the statutory criminal law to be held captive by the popular misconceptions of who the LGBTs are. It cannot be forgotten that discrimination is antithesis of equality and that it is the recognition of equality, which will foster the dignity of every individual.”

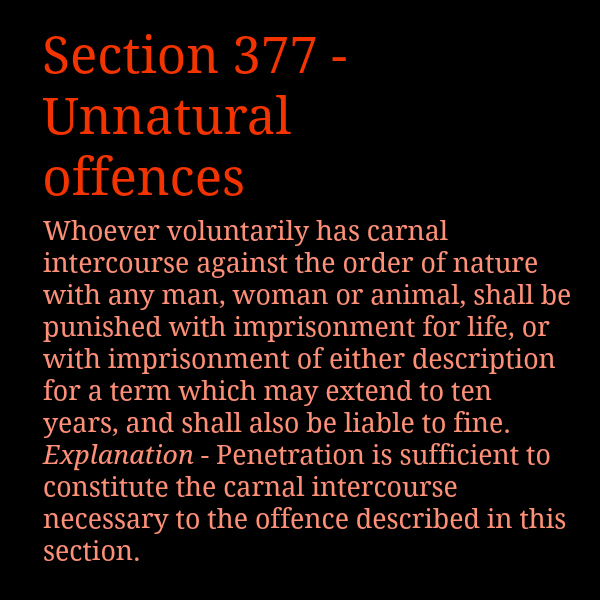

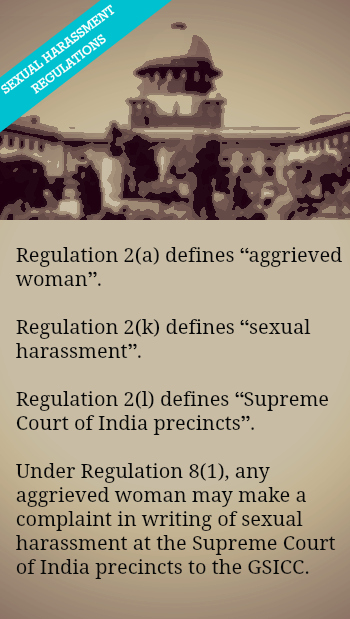

Today, after a long, convoluted appeals process that stretched over four years, the Supreme Court of India overturned the Delhi High Court’s 2009 judgment, thereby re-criminalising gay relationships. In doing so, the Supreme Court of India stands apart — in disgraced isolation — from the judiciary in every other democracy in the world — including developing countries like South Africa, Nepal, Mexico, and Brazil.

In throwing the ball back to the executive branch, the judges sought to couch their decision in terms of showing constitutional deference for the role of the executive. The Supreme Court however, has never shown hesitation in striking down central and state laws and has been perfectly willing to create laws (mostly good) out of thin air, such as the recent judgment banning criminals from contesting elections. In this particular case, the Indian government’s final submission supported the repeal of Section 377 (that is, supported decriminalisation of gay relationships). This would indicate that the deference to executive authority was a fig leaf — enabling the justices to render a regressive and prejudiced decision without overtly appearing to do so. The news media rightly greeted the ruling with headlines like “SC: Gay sex illegal” and “Gay Sex is a criminal offense rules Supreme Court”. For once, the media’s inability to handle nuance is working in favour of truth.

While India’s brave community of LGBT activists and their heterosexual allies will continue to fight for equality — one that they will doubtless win in the long run; in the short term, this decision does real damage to the lives of gay people who are out or in the closet. It will expose lesbians and gays to even more harassment and persecution from the police; give fresh institutional cover to discriminatory practices in every aspect of life — housing and employment among others, and could shrink the already rather limited spaces that the LGBT community has carved out for themselves in public life.

Today, the Supreme Court of India has abjectly failed in its fundamental duty to protect the fundamental rights of an individual and of minorities. Here’s hoping Justices Singhvi and Mukhopadhyaya will see the repudiation of their reasoning by the same Supreme Court in their lifetimes.

(Abhay Prasad is a graduate of IIT Bombay and IIM Ahmedabad and a former volunteer editor of Trikone Magazine, the oldest South Asian LGBT magazine in the U.S. His blog is here.)