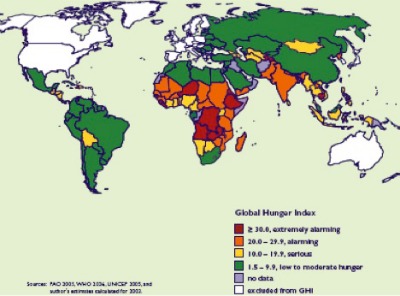

Along with many African countries, India stands at the verge of facing “extremely alarming” levels of hunger in its population and does not fare much better than Bangladesh or Nepal (see map below). According to statistics from the World Bank (see here), forty-eight per cent of children in India are underweight while only twenty-nine per cent in Sri Lanka are. Forty-six per cent of children in India are stunted and sixteen per cent are wasted but for Sri Lanka, these numbers are at fourteen per cent and fourteen per cent respectively. India’s infant mortality rate (sixty-two per cent) is much higher than any other county in South Asia except Pakistan. Excluding similar human development criteria from accounts of development and growth is a cruel ideological sleight of hand.

Along with many African countries, India stands at the verge of facing “extremely alarming” levels of hunger in its population and does not fare much better than Bangladesh or Nepal (see map below). According to statistics from the World Bank (see here), forty-eight per cent of children in India are underweight while only twenty-nine per cent in Sri Lanka are. Forty-six per cent of children in India are stunted and sixteen per cent are wasted but for Sri Lanka, these numbers are at fourteen per cent and fourteen per cent respectively. India’s infant mortality rate (sixty-two per cent) is much higher than any other county in South Asia except Pakistan. Excluding similar human development criteria from accounts of development and growth is a cruel ideological sleight of hand.

India is also home to some of the world’s largest food schemes. They include:

– Entitlement feeding programmes such as the Integrated Child Development Scheme for all children under six, and pregnant and lactating mothers; and the Mid Day Meal Scheme, for all primary school children.

– Food subsidy programmes such as the targeted public distribution system (“PDS”), which delivers thirty-five kilograms of subsidised food grains each month and the Annapurna scheme, under which ten kilograms of food grain are distributed to the destitute poor each month.

Employment programmes such as the National Rural Employment Scheme, which provides hundred days of employment at minimum wages.

Social safety net programmes such as the National Old Age Pension Scheme featuring a monthly pension for those below the poverty line and the National Family Benefit Scheme featuring compensation in case of the death of the breadwinner in families below the poverty line.

It is no secret that the implementation of these schemes has been marred by large-scale corruption and inefficiency. There are parts of the country where people received their first ration cards as late as 2006-07. All of us were also appalled at the tragic poisoning of children’s mid-day meals in Bihar.

At the same time, some state governments have been able to significantly improve upon these central schemes and deliver much-needed benefits to the people. The picture would be incomplete if we were to overlook the successful working of the PDS in Chhattisgarh and Tamil Nadu and many other parts of the country where at least half the monthly nutritional requirements of a household are met by the provisions from the PDS. Therefore, strengthening government intervention based on such successes is a workable and accountable solution to hunger and malnutrition.

A landmark in the way to resolve the artificially constructed “food crisis” in India has been the Supreme Court’s interventions in the PUCL case since 2001. The longest running mandamus on the right to food in the world, this case has provided civil society an anchor to both engage and confront the State on issues of food insecurity and employment. It has been successful in making the discourse of food security one of the most prominent concerns of policymakers. The case has resulted in:

– a universal MDMS and ICDS. 120 million children get school meals;

– restricting the lowering of the below-poverty-line quotas by the government of India;

– increasing the off-take of subsidised food grains through the targeted public distribution system;

– increasing the budgetary allocation for the ICDS and old age pensions threefold; and

– the passage of the National Rural Employment Guarantee Act, 2005.

Even as these attempts at reforms in governance and increase in government accountability have transformed all food-related schemes into legal entitlements, we are still short of achieving what can be called a right to food. The National Food Security Bill, 2013 that has now been passed by the Parliament fails to universalise measures for ensuring food security for the entire population. There can still be conspicuously unfair errors of exclusion, as the criteria for identifying the beneficiaries of this law remain unclear. Moreover, the provisions of this Act still focus on individual redressal rather than systemic changes. Some campaigners for food security are also concerned that even the limited achievements of the new law are largely an outcome of judicial activism — a fact that does not sit comfortably with our aspirations of a popular democracy.

The popular mobilisations on the right to food are a confluence of diverse interests that have arrived at the consensus that the right to food is more than just about food. The campaign for it has worked closely with movements for government accountability, right to work, gender justice, and equitable access to health and education. It is only in the fulfillment of all these requirements for a life with dignity that something like a right to food will actually be effective. This is a “broader view” of food security and the quest for it will remain unrequited unless all these goals are reached along with the universalisation of the right to food.

(Vaibhav Raaj is a PhD candidate at the Centre for Political Studies in Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi.)