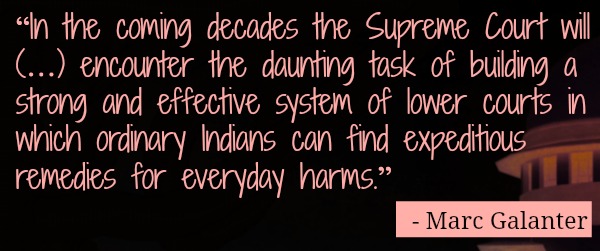

Even though India’s constitutional courts have played and continue to play a significant role in the development of the country’s human rights jurisprudence, they are only a small fraction of the judicial machinery. The trial courts, from the district and sessions courts to the courts of magistrates and civil judges, are the cogs that keep the system running. Often, claims are adjudicated locally to enforce statutory remedies and courts have to hear matters relating to bail, forest rights, labour rights, land, extra-judicial executions, caste atrocities, sexual violence, and many more subjects. Mostly, the violations are not egregious enough to necessitate the intervention of a constitutional court. Rather, they are the “everyday harms” that Galanter refers to (below). Moreover, the orders of the constitutional courts have little value till they are implemented at the grassroots level, for which trial courts play a critical role.

Even though India’s constitutional courts have played and continue to play a significant role in the development of the country’s human rights jurisprudence, they are only a small fraction of the judicial machinery. The trial courts, from the district and sessions courts to the courts of magistrates and civil judges, are the cogs that keep the system running. Often, claims are adjudicated locally to enforce statutory remedies and courts have to hear matters relating to bail, forest rights, labour rights, land, extra-judicial executions, caste atrocities, sexual violence, and many more subjects. Mostly, the violations are not egregious enough to necessitate the intervention of a constitutional court. Rather, they are the “everyday harms” that Galanter refers to (below). Moreover, the orders of the constitutional courts have little value till they are implemented at the grassroots level, for which trial courts play a critical role.

Advocates play a key role in ensuring litigants — particularly those is vulnerable positions — are able to access this system. To understand how human rights are enforced and adjudicated in India, it is important to understanding the crucial space of trial litigation, and for that, this column will survey the courts as well as the advocates who practice in this space — who they are, what they do, and what they can do better.

The fora

Section 30 of the Protection of Human Rights Act, 1993 empowers every state government to notify designated sessions courts as “Human Rights Courts” for providing speedy trial in cases of offences involving violations of human rights. As of 2011, however, these courts had only been operational in West Bengal. Elsewhere, human rights continue to be litigated before regular courts. Specific human rights claims may also be raised before the National Human Rights Commission, the State Human Rights Commissions, and quasi-judicial fora comprising officials of the executive such as sub-divisional magistrates and forest officers.

The advocates

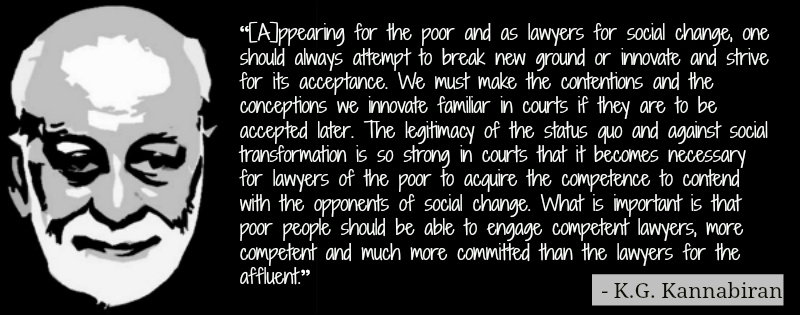

The advocate’s role is critical in the effective enforcement of rights. While civil society activists and organisations play an important role in organising human rights movements, advocates are better placed to articulate causes in the language of the law and obtain judicial remedies. Intimately connected to the client and the cause, human rights advocates can also bring out the political in the law, using it both as a means of obtaining remedies as well as a rallying point for a cause. As Kannabiran points out, this often involves creating awareness around an issue and sensitising the courts about the problems that they may not be aware of. Human rights lawyering in this sense, is as much about creating and sustaining movements as about ensuring justice in individual cases. Both these aspects are anchored very strongly in values of justice and fraternity that flow from the Constitution and international human rights treaties such as the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. In this way, the process of human rights lawyering offers a way of reclaiming the law for us, the people. It uses a moral and ethical framework located within the Constitution of India that is also supported by international instruments.

Some of the most prominent examples of human rights lawyering internationally come from the American Civil Liberties Union (“ACLU”) in the United States. Through over eight decades of its existence, the ACLU has used a combination of strategic litigation and public mobilisation to fight for the protection of human rights guaranteed under the Constitution of the United States of America. A number of organisations have been involved in human rights lawyering in India, including the People’s Union for Civil Liberties, the Human Rights Law Network, the Andhra Pradesh Civil Liberties Committee, the Centre for Social Justice, the Chhattisgarh Mukti Morcha, the Extra Judicial Execution Victim Families Association and many more, both at the constitutional courts as well as at the grassroots level. Further, several independent advocates and human rights activists have been tirelessly — and often in the face of stiff opposition and even threats to their lives — advancing the cause of human rights lawyering at the trial courts across the country.

Better human rights lawyering at the trial courts

A number of issues are particular to human rights lawyering at the trial courts. The remedies available through trial courts are different from those available at the constitutional courts. Trial courts, for instance, do not have the power to issue writs but have important statutory powers under the Code of Criminal Procedure, 1973 and other statutes. The techniques and strategies of advocates at these courts and the challenges they face reflect these differences.

As with lawyering anywhere, mentorship at the bar and the ability to network with other lawyers doing similar work, are invaluable to improving the standard of human rights lawyering at the trial courts. Institutional help in the form of NGOs and similar organisations, also make a difference to the extent and effectiveness of interventions made by human rights advocates. Documenting these practices through interviews with advocates involved in human rights lawyering at trial courts across the country, is expected to initiate useful conversations and expand the collective body of knowledge on this area.

As with lawyering anywhere, mentorship at the bar and the ability to network with other lawyers doing similar work, are invaluable to improving the standard of human rights lawyering at the trial courts. Institutional help in the form of NGOs and similar organisations, also make a difference to the extent and effectiveness of interventions made by human rights advocates. Documenting these practices through interviews with advocates involved in human rights lawyering at trial courts across the country, is expected to initiate useful conversations and expand the collective body of knowledge on this area.

While there is a fair amount of literature on human rights lawyering in terms of writ remedies and public interest litigation at the constitutional courts, the trial court space has not been fully mapped. The results of a pioneering study across India by the Alternative Law Forum as part of their Human Rights Lawyering Project are eagerly awaited. Given that the several human rights movements in India do not always engage with each other and that a “community” of human rights advocates does not fully exist, efforts to network them and document learning experiences are critical to the advancement of human rights lawyering. It is hoped that this column will bridge some of these gaps and contribute to the growth of human rights lawyering at the trial courts.

(Manish is a legal researcher based in Delhi.)

References

– B.N. Kirpal et al (eds.), Supreme but not Infallible: Essays in Honour of the Supreme Court of India (Oxford University Press, 2004).

– Jayanth Krishnan, Lawyering for a Cause and Experiences from Abroad, 94(2) California Law Review 575 (2006).

– Justice P. Sathasivam, Role of Courts in Protection of Human Rights, speech at the Tamil Nadu Judicial Academy (2012).

– K.G. Kannabiran, A One in a Century Rights Activist, 44(46) Economic and Political Weekly 8 (2009).

– Marc Galanter, The Study of the Indian Legal Profession, 3 Law and Society Review 201 (1968).

– Ruth Cowan, Women’s Rights through Litigation: An Examination of the American Civil Liberties Union Women’s Rights Project, 8 Columbia Human Rights Law Review 373 (1976-1977).

– Usha Ramanathan, Human Rights in India: A Mapping, (2001).