With a series of posts that will appear here under the header “On Trial”, I want to give lawyers who are about to embark on their professional journey, a flavour of what I have learnt in six years as a trial and appellate litigator. I believe that although law schools equip students with some basic skills, by and large they do not prepare them for the rigours and demands of a law practice. I hope that my posts here will help them scale the learning curve faster and with fewer mistakes.

With a series of posts that will appear here under the header “On Trial”, I want to give lawyers who are about to embark on their professional journey, a flavour of what I have learnt in six years as a trial and appellate litigator. I believe that although law schools equip students with some basic skills, by and large they do not prepare them for the rigours and demands of a law practice. I hope that my posts here will help them scale the learning curve faster and with fewer mistakes.

Another recent trend that I noticed was that students are keen to take “activist” positions without doing their research on the law as it exists. There is nothing wrong in taking positions or having opinions on matters of policy but lawyers need to first have clarity on what the law is before commenting on what the law ought to be. That apart, no matter how good one is at substantive law, it is important to know how to present and prove a case in a court of law. Command over procedure is equally important and procedure is best learnt through application and practice.

Introspect when you make errors

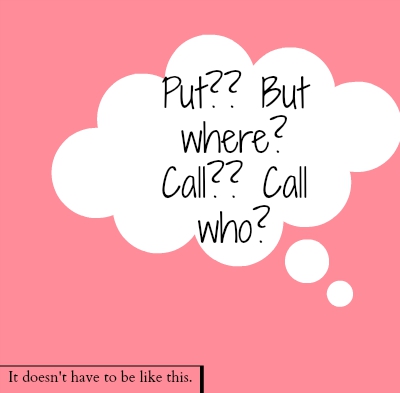

Once you join the profession, you will realise that most experienced lawyers do not have the time to sit you down and explain how things work. You learn on the job and naturally, are bound to commit a lot of mistakes. The experience can be soul-shattering and may shake your confidence in yourself. What has helped me in these moments is the realisation that a lawyer must not only be a doer, but must also be a conscious observer of his actions. In other words, every time you goof up, your first instinct must be to look inward and be brutally honest, instead of passing the buck or making anyone else the scapegoat. This realisation led me to create my own “Mistakes Log” which has captured nearly every mistake I have committed in the last six years. I have preffered to assess the quality of my journey using the number and quality of my mistakes because success is the product of several factors, many of which are external and are beyond one’s power.

Once you join the profession, you will realise that most experienced lawyers do not have the time to sit you down and explain how things work. You learn on the job and naturally, are bound to commit a lot of mistakes. The experience can be soul-shattering and may shake your confidence in yourself. What has helped me in these moments is the realisation that a lawyer must not only be a doer, but must also be a conscious observer of his actions. In other words, every time you goof up, your first instinct must be to look inward and be brutally honest, instead of passing the buck or making anyone else the scapegoat. This realisation led me to create my own “Mistakes Log” which has captured nearly every mistake I have committed in the last six years. I have preffered to assess the quality of my journey using the number and quality of my mistakes because success is the product of several factors, many of which are external and are beyond one’s power.

In these posts, I will draw on my experiences (both personal and vicarious) and share a few practical inputs. I will not, unless absolutely necessary, use much legalese or cite precedent because, thanks to the tools and databases available to most lawyers and even non-lawyers these days, it is not really difficult to read up on the case law on any issue, procedural or substantive. That said, it is important to bear in mind that individual journeys vary and consequently, the lessons drawn as well. Therefore, caveat lector applies to what I have to say.

I will write about aspects of both civil and criminal litigation. Under civil litigation, I will discuss pleadings, interim reliefs, discovery, the trial, oral arguments, and finally, appellate reliefs. Let us look at the general approach to drafting and pleadings first.

Orders VI to VIII of the Code of Civil Procedure, 1908 deal with pleadings. A pleading is defined in Order VI, Rule 1 to mean a plaint or a written statement. Orders VII (read with Section 26) and VIII deal with the requirements of a plaint and written statement respectively and the rules that govern pleadings generally are laid down in Order VI. Adherence to these rules, it is important to understand, is mandated only to the extent that the ends of justice are advanced. Departures from them are not uncommon in practice, nor are they frowned upon by courts unless they are egregious or fatal. This is not to trivialise or discourage adherence to these rules, it is merely an observation about the state of affairs.

In practice, when it comes to pleadings, the tendency is to play safe. This manifests in several ways – right from faithfully adopting boilerplates to making repetitive submissions for the fear of being accused of not denying an allegation or a claim or an assertion by the other side, so much so that even evidence affidavits turn out to be slavish reproductions of pleadings.

Drafting need not be a chore

Although there is a sense of safety in treading the conventional path and in reiterating, errors tend to creep in when templates are adopted without discrimination and that could cause embarrassment when they are scrutinised by the opposing side during trial. Also, from the litigator’s point of view, drafting becomes a chore as opposed to the active learning and simulation exercise it is supposed to be, which certainly does not bode well for the quality of the final product. So how does one go about drafting pleadings?

For starters, it would help to bear in mind that drafting is different from writing. Although good writing skills contribute to good drafting, being adept at English or at writing do not necessarily translate to good drafting. In fact, sometimes there is even a mismatch between the flair that people exude for spoken English and the quality of their writing, and even the converse holds good. Therefore, although a fair command over language and lucidity in writing are essential, what separates writing from drafting, is the realisation that:

(a) it has a real and serious bearing on the fortunes of a litigant.

(b) it caters to an audience that is trained in the law,

(c) it has to present the litigant’s case in the best possible manner while conforming to the requirements of the law, and finally

(d)it will be subjected to withering adversarial dissection by the opposing party (a draft looks great only until the opposing party steps into the picture).

Bearing all of this in mind helps lend sharpness to a draft. That said, given the critical role of pleadings, it is natural to be bogged down by the tedium and gravity of the process. So, given that in the initial years of practice, a litigator is primarily expected to be a researcher and a drafter, how does one quickly churn out sharp drafts and yet make it an engaging exercise?

Although it may not always be desirable or possible, crisp and concise pleadings make life easier for the litigator and the court, more so for the latter since it does not have the time or patience for rambling pleadings. In fact, the volume of pleadings invariably weans a court away from hearing a matter even if the dispute is otherwise fairly straightforward. That said, a litigator’s primary challenge in keeping pleadings to the point is to convince the client that volume of pleadings is not directly proportional to the strength of the case and certainly does not guarantee a successful outcome. This is where the litigator has to fall back on her or his client counselling skills to set reasonable expectations to the client. While it is true that not every client may be convinced, the effort is worth it.

Reflect on what you want to present to the court

The key to clear-cut pleadings is to spend time thinking about what one wishes to present to the court before starting to draft. This means that the broader and the narrower points must be broadly identified and supported with factual and legal research. Subsequently, the litigator must decide the sequence in which the points must be captured so that the court can quickly grasp the nub of the matter without having to wade through several pages. This sequence must not be treated as final because during the course of drafting, an alternate sequence of arguments may seem more logical, or appeal from a strategic perspective. Although this approach may seem time-consuming at first, the advantages of spending time on the matter before drafting will become apparent with time as one becomes more adept at identifying issues and developing a feel for the forum. After all, in our profession, hard work is not measured by the number of hours spent in thoughtless labour or the number of pages drafted. The effort lies in rumination.

J.Sai Deepak, an engineer-turned-litigator, is an Associate Partner in the Litigation Team of NCR-based Saikrishna & Associates. Sai is @jsaideepak on Twitter and is the founder of the blawg “The Demanding Mistress” where he writes on economic laws, litigation and policy. All opinions expressed here are academic and personal.