I have often heard it lamented that India lacks U.S.-style discovery mechanisms at trial. While I am no expert on U.S. procedural law, I believe that Indian civil procedure contains substantial mechanisms for discovery. Let us now look at the mechanisms available under the Code of Civil Procedure, 1908 (“CPC”) including those recently introduced to the CPC through the Commercial Courts, Commercial Division and Commercial Appellate Division of High Courts Act, 2015 (“Commercial Courts Act“). Employed effectively, they can narrow down the scope of facts and issues that need examination at trial.

I have often heard it lamented that India lacks U.S.-style discovery mechanisms at trial. While I am no expert on U.S. procedural law, I believe that Indian civil procedure contains substantial mechanisms for discovery. Let us now look at the mechanisms available under the Code of Civil Procedure, 1908 (“CPC”) including those recently introduced to the CPC through the Commercial Courts, Commercial Division and Commercial Appellate Division of High Courts Act, 2015 (“Commercial Courts Act“). Employed effectively, they can narrow down the scope of facts and issues that need examination at trial.

Discovery under the CPC

Section 30 of the CPC provides for a court’s power to order discovery. At any time during the conduct of a suit, this provision empowers a court, either of its own motion or on the application of a party, to pass necessary and reasonable orders relating to the delivery and answering of interrogatories; the admission of documents and facts; and the discovery, inspection, production, impounding, and return of documents or other material objects that may be produced as evidence. The provision also empowers a court to issue summons to persons whose attendance is required either to give evidence or to produce documents or other objects that may be led in evidence. A court can also order any fact to be proved by way of an affidavit. While it is commonly assumed that only Order XI of the CPC corresponds to Section 30, Orders XII, XIII, and XVI also contain provisions that relate to Section 30.

What’s the role of a court in discovery proceedings?

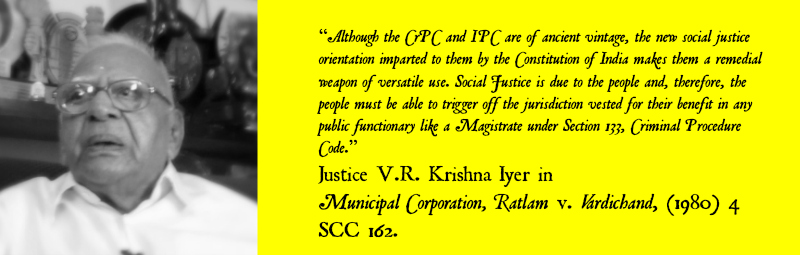

The framework that emerges from a combined reading of Section 30 and Orders X, XI, XII, XIII, XVI, and XVIII informs us that the assumption that Indian courts lack powers of discovery because they adhere to the adversarial system of justice may not be true. In Maria Margadia Sequeria v. Erasmo Jack De Sequeria (2012), the Supreme Court, holding that discovery was one of the main purposes of the existence of courts, made some telling observations:

“A judge in the Indian System has to be regarded as failing to exercise its jurisdiction and thereby discharging its judicial duty, if in the guise of remaining neutral, he opts to remain passive to the proceedings before him. He has to always keep in mind that “every trial is a voyage of discovery in which truth is the quest”. In order to bring on record the relevant fact, he has to play an active role; no doubt within the bounds of the statutorily defined procedural law.

41. World over, modern procedural Codes are increasingly relying on full disclosure by the parties. Managerial powers of the Judge are being deployed to ensure that the scope of the factual controversy is minimized.

42. In civil cases, adherence to Section 30 CPC would also help in ascertaining the truth. It seems that this provision which ought to be frequently used is rarely pressed in service by our judicial officers and judges.”

The Court also quoted from the report of the Malimath Committee, which had highlighted the drawbacks in a strictly adversarial system and recommended that courts be statutorily mandated to become active seekers of truth. This fundamental shift in the Indian approach to disputes must be borne in mind when one invokes the mechanisms for discovery. In A. Shanmugam v. Ariya K.R.K.M.N.P.Sangam (2012), the Court, apart from reiterating the ratio of Maria Margadia Sequeria, categorically observed that ensuring discovery and production of documents and a proper admission or denial is imperative for the effective adjudication of civil cases.

Bar raised by Commercial Courts Act

The Commercial Courts Act, 2015 builds on this approach further by introducing an improved discovery mechanism, evident from the language and structure of Rules 1 to 5 in the revised Order XI, which is specific to suits of a commercial nature. The spirit of the revised framework is perhaps best captured by Sub-rule 12 of Rule 1. It unequivocally states that the duty to disclose documents that have come to the notice of the party shall continue until the disposal of the suit. It goes without saying that the reference here is to documents, which are relevant and necessary to decide any question that is germane to the dispute before the court. Critically, both parties are expected to file a list of all relevant documents which are in their power, possession, or control regardless of whether those documents support or undermine their respective positions on merits. Clearly, the bar has been raised under the Commercial Courts Act and both the parties and the courts have access to fairly effective discovery options to facilitate expeditious disposal of suits. The actual employment of these options, of course, remains to be seen.

In the next part of this series, I shall discuss framing of issues and the commencement of trial.

J. Sai Deepak is an engineer-turned-law firm partner-turned-arguing counsel. Sai is the founder of Law Chambers of J. Sai Deepak and appears primarily before the High Court of Delhi and the Supreme Court of India. He is @jsaideepak on Twitter and is the founder of the blawg “The Demanding Mistress” where he writes on economic laws, litigation, and policy. All opinions expressed here are academic and personal.