In our previous post, we looked at optional arbitration clauses — where the parties may arbitrate their disputes. Such clauses, we found, may be rejected for being uncertain. There is no certainty about the parties’ intention to arbitrate or to oust the jurisdiction of the competent national court.

In our previous post, we looked at optional arbitration clauses — where the parties may arbitrate their disputes. Such clauses, we found, may be rejected for being uncertain. There is no certainty about the parties’ intention to arbitrate or to oust the jurisdiction of the competent national court.

In this post, we look at a specific type of optional clause — a unilateral option clause. Common in finance contracts, a unilateral option clause provides one of the contracting parties (typically the party with the stronger bargaining position, like the bank in a financing contract) with the flexibility of selecting between arbitration and litigation for the resolution of contractual disputes.

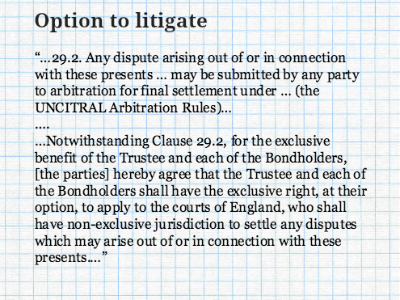

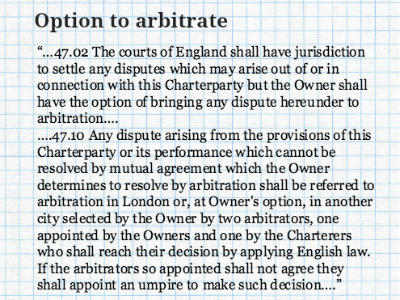

A unilateral option clause can be an arbitration clause with the option to litigate or a jurisdiction clause with the option to arbitrate. See the two examples below.

English courts have held both to be enforceable. Other jurisdictions however, may refuse to recognise such clauses for the following reasons.

– Uncertainty: The unilateral option could be construed as undermining the requirement to clearly agree to submit disputes to arbitration.

– Lack of mutuality: The unilateral option may be held to be unenforceable because it does not have the consent of all parties to submit to arbitration. Indian courts have used this argument in the past to invalidate such clauses.

– Unconscionability: The unilateral option may be considered unconscionable (and therefore, invalid), for example in consumer and employment contracts where the contractual parties are not commercial counterparties.

Recent French and Russian decisions for example, have invalidated unilateral clauses — leading to concerns in the international arbitration community that more and more jurisdictions will follow this trend. In the French Rothschild case, on September 26, 2012, the court invalidated a unilateral jurisdictional clause (offering one party the choice between two national courts) because of its potestative nature — it made the fulfilment of the agreement depend upon an event, which only one of the contracting parties had the power to make happen.

Similarly, a Russian decision, on June 19, 2012, held that a unilateral dispute resolution clause was unenforceable on the ground of unconscionability – as it was “contrary to the basic principle of procedural equality of the parties, adverse to the nature of the dispute resolution process, and breach the balance between the interests of the parties.”

The drafting lesson here is to firstly, avoid using optionality clauses just for the sake of it — only have them in the contract if your client (assuming your client has the stronger bargaining position and can ask for it) really sees a need for the flexibility it provides. Secondly, check the validity of the clause that you have drafted under the law governing your arbitration clause, the law at your seat, the law at the chosen court (for the litigation option), and the law at your likely place of enforcement.

(Sindhu Sivakumar is a member of the faculty on myLaw.net.)