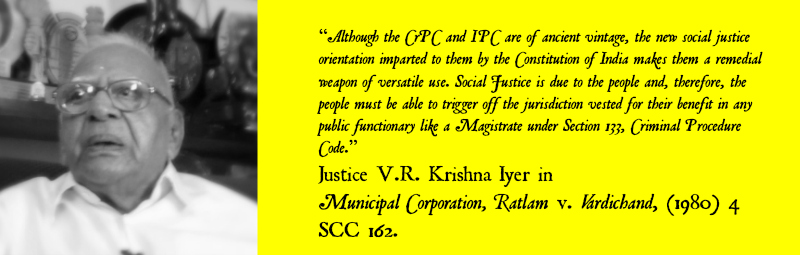

Over three decades after the Supreme Court recognised and encouraged the use of the judiciary to enforce remedies against the state, Sarojani Tamshetty, 29, an advocate practising in Solapur, is using Section 133 of the Code of Criminal Procedure, 1973 (“CrPC”) to ensure that basic rights, including the rights to drinking water and sanitation, are not denied to the citizens of her city. Sections 49 and 50 of the Maharashtra Municipalities Act, 1965 obligates every municipal corporation to provide drinking water and sanitation to citizens. Solapur had been at the receiving end of its municipality’s inaction in this regard. The urban poor, doubly hit by their inability to access municipal offices, were most severely affected. Ms. Tamshetty stepped in and filed a complaint before the jurisdictional magistrate under Section 133 of the CrPC. An order was issued to the municipal authorities and the municipality eventually took action and commissioned water supply and sanitation projects.

Using legal notices to secure rights for the urban poor

In non-municipal areas, the district administration and revenue authorities wield significant power. While the ordinary method of seeking redress from such authorities is by submitting applications and representations, it leaves the question of what to do in case the authority in question fails to respond. Ms. Tamshetty came up with a unique way of resolving this. After submitting several representations to the Solapur district administration for the implementation of the Sanjay Gandhi Niradhar Anudan Yojana (a scheme for provision of financial assistance to destitute persons) and not receiving any response, she issued a legal notice to the District Collector. The notice resulted in funds being sanctioned for the scheme and the appointment of a committee for receiving applications and disbursing the amount.

In non-municipal areas, the district administration and revenue authorities wield significant power. While the ordinary method of seeking redress from such authorities is by submitting applications and representations, it leaves the question of what to do in case the authority in question fails to respond. Ms. Tamshetty came up with a unique way of resolving this. After submitting several representations to the Solapur district administration for the implementation of the Sanjay Gandhi Niradhar Anudan Yojana (a scheme for provision of financial assistance to destitute persons) and not receiving any response, she issued a legal notice to the District Collector. The notice resulted in funds being sanctioned for the scheme and the appointment of a committee for receiving applications and disbursing the amount.

Legal notices have also been used to good effect by Salma Bano, a 26-year old lawyer practising in Nabarangpur, Odisha. An unscrupulous contractor had illegally confiscated the job cards of a few poor labourers under the National Rural Employment Guarantee Act, 2005 (“NREGA”). After they approached her, Ms. Bano issued a legal notice to the contractor, directing him to return the cards. These cards were returned to their rightful owners.

Litigating for victims of domestic violence

She also handles a number of cases of domestic violence, where besides providing legal assistance, the lawyer is often required to extensively counsel her client, who may also be in need of medical assistance. In most of these cases, the victims seek an end to the violence and a means of sustenance, but do not wish to initiate criminal proceedings against their violent husbands. The Protection of Women from Domestic Violence Act, 2005 is a useful tool in such cases, for claiming a variety of civil remedies including protection orders, residence orders, and maintenance. The advocate also has to coordinate with protection officers for getting these orders implemented. Ms. Bano, who hails from an educationally backward area and a socially conservative community, takes pride in convincing members of her community to come out of their conservative mindsets, through her use of the law for making claims that have contributed to the advancement of her community. Says she, “The same people who opposed me earlier, now come to me seeking advice with their problems.”

She also handles a number of cases of domestic violence, where besides providing legal assistance, the lawyer is often required to extensively counsel her client, who may also be in need of medical assistance. In most of these cases, the victims seek an end to the violence and a means of sustenance, but do not wish to initiate criminal proceedings against their violent husbands. The Protection of Women from Domestic Violence Act, 2005 is a useful tool in such cases, for claiming a variety of civil remedies including protection orders, residence orders, and maintenance. The advocate also has to coordinate with protection officers for getting these orders implemented. Ms. Bano, who hails from an educationally backward area and a socially conservative community, takes pride in convincing members of her community to come out of their conservative mindsets, through her use of the law for making claims that have contributed to the advancement of her community. Says she, “The same people who opposed me earlier, now come to me seeking advice with their problems.”

For Begum Rehana, the path to becoming a lawyer started at home – out of her own lived experience with domestic violence. Having gone through the difficulty of finding a supportive and affordable lawyer, especially in the conservative neighbourhood of the Old City in Hyderabad, she vowed never to be dependent on anyone again, and began studying and later practising law. Today, she enables several poor women, deserted by their husbands, to claim their legal rights to maintenance and residence. The Muslim Women (Protection of Rights on Divorce) Act, 1986, as interpreted by the Supreme Court, obligates a husband to make reasonable provision for maintenance of his wife (for her entire lifetime) within the iddat period (approximately three months from the date of the divorce). Ms. Rehana has used this law to good effect, helping several women obtain maintenance from their husbands. In circumstances where the husband is unable to pay, this responsibility ultimately falls on the State Wakf Board. In some such cases, Ms. Rehana has also obtained orders from a family court, directing the Wakf Board to pay maintenance to the destitute woman. The matter does not end there. The advocate also has to repeatedly visit the office of the Wakf Board and file right to information applications to ensure that the amount is finally disbursed to the woman.

Litigating cases of domestic violence or maintenance involves a fair amount of client counselling, especially during the trial at the stage of cross-examination. Often, women in such situations are already overwhelmed by their circumstances, and hence it is extremely important for an advocate to speak to the client and build up her confidence, so that she is able to withstand gruelling cross-examination by the opposing counsel. The most important thing, according to Rehana, both legally and psychologically, is to demand maintenance as a matter of right rather than charity.

Litigating cases of domestic violence or maintenance involves a fair amount of client counselling, especially during the trial at the stage of cross-examination. Often, women in such situations are already overwhelmed by their circumstances, and hence it is extremely important for an advocate to speak to the client and build up her confidence, so that she is able to withstand gruelling cross-examination by the opposing counsel. The most important thing, according to Rehana, both legally and psychologically, is to demand maintenance as a matter of right rather than charity.

Spreading awareness, filing RTI applications

Ms. Rehana also works with a local women’s collective, Shaheen, on spreading awareness in her community, especially among women, about access to government schemes and entitlements, such as scholarships, ration cards, and other government schemes providing financial assistance to women who have been victims of violence. Other means of enabling people to claim their entitlements under various schemes or legislations include using the Right to Information Act, 2005 to get information about the implementation of schemes and budgetary allocations. Generally, Ms. Rehana’s experience has been that officials are sometimes uncooperative or reluctant to disclose information but tend to become responsive when proceedings are initiated before the appellate authority or the state information commissions.

Overcoming the absence of role models

Ms. Tamshetty, Ms. Bano, and Rehana also work with the district legal services authority, as empanelled lawyers or otherwise. This gives them exposure to a wide range of legal issues faced by people who are socially and economically backward.

As with any other profession, litigation is also gendered. All of them report having encountered hurdles and obstacles in their career path, ranging from opposition from their families to sexist behaviour from their male colleagues. A major issue is the absence of senior female advocates at the district court level, for mentorship or just as role models. Another obstacle is that at the district court level, women are discouraged from taking up criminal litigation because it is “not suitable” for them, and advised to stick to the civil side instead. Institutional and organisational support for grassroots lawyers however, is available in the form of fellowships, including the Human Rights Law Defenders program by the Sahyog Trust, the Young Lawyers for Justice fellowships by the Committee for Legal Aid to Poor, and the Lawyers For Change fellowships by Econet and Centre for Social Justice. Ms. Tamshetty, Ms. Bano, and Ms. Rehana, have availed of one or more of these fellowships, and recognise their great value as learning resources, especially in terms of enabling them to interact and learn from other advocates doing similar work in other parts of the country. Given that human rights lawyering is not commercially remunerative, such fellowships also provide useful financial support.

(Manish is a legal researcher based in Ahmedabad.)

My first court visit, during an internship, remains etched in my memory. Visitor pass in hand, I entered the Supreme Court, gazing awestruck at the beautiful façade. I set out to find Courtroom Number 12. How hard could it be? Very hard indeed. It took me half an hour, during which I was even ushered out of a judges’ enclosure, and I missed the matter. I later discovered that this was a rite of passage. All my classmates had stories of getting lost in the winding corridors of court complexes.

My first court visit, during an internship, remains etched in my memory. Visitor pass in hand, I entered the Supreme Court, gazing awestruck at the beautiful façade. I set out to find Courtroom Number 12. How hard could it be? Very hard indeed. It took me half an hour, during which I was even ushered out of a judges’ enclosure, and I missed the matter. I later discovered that this was a rite of passage. All my classmates had stories of getting lost in the winding corridors of court complexes. Though a very interesting one, my process of discovering courts left me with some concerns. Courts seemed to pay little or no attention to the ordinary litigant. Lawyers on the other hand, were demigods. Buildings have complex layouts with little or no directional assistance to get around. Security passes at the higher courts automatically exclude litigants without readily available identity proofs but anyone in black and white will manage to enter them unchecked. The bureaucratic dependence on files breeds corruption by creating more palms to grease for any work that needs to be done. Given the scale of the problem, it seems the common litigant can only hope to snigger and chip away, one date at a time.

Though a very interesting one, my process of discovering courts left me with some concerns. Courts seemed to pay little or no attention to the ordinary litigant. Lawyers on the other hand, were demigods. Buildings have complex layouts with little or no directional assistance to get around. Security passes at the higher courts automatically exclude litigants without readily available identity proofs but anyone in black and white will manage to enter them unchecked. The bureaucratic dependence on files breeds corruption by creating more palms to grease for any work that needs to be done. Given the scale of the problem, it seems the common litigant can only hope to snigger and chip away, one date at a time.