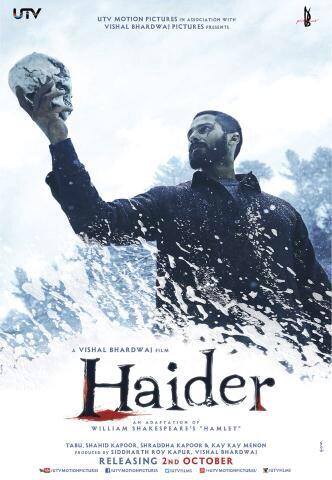

The first scene in the fifth act of William Shakespeare’s Hamlet: Prince of Denmark is perhaps the most unflattering prose that the bard wrote on the subject of lawyers. Before holding up a skull, Hamlet points to an exhumed grave and asks if the occupant was a lawyer. Proceeding to mock lawyers who do not appreciate the limits of law, Hamlet remarks that the only property rights accorded after burial are titles to coffins. This derision of the legal system was not included Vishal Bhardwaj’s film adaptation Haider, perhaps with good reason, given the recent legal troubles the film has run into.

The first scene in the fifth act of William Shakespeare’s Hamlet: Prince of Denmark is perhaps the most unflattering prose that the bard wrote on the subject of lawyers. Before holding up a skull, Hamlet points to an exhumed grave and asks if the occupant was a lawyer. Proceeding to mock lawyers who do not appreciate the limits of law, Hamlet remarks that the only property rights accorded after burial are titles to coffins. This derision of the legal system was not included Vishal Bhardwaj’s film adaptation Haider, perhaps with good reason, given the recent legal troubles the film has run into.

Haider, which adapted the play to the political confines of Kashmir, was always going to be controversial. There did not seem reason however, to suggest that such controversy would involve the legal system. After all it had a valid censor board certificate, issued after complying with a demand for six cuts to be made to the original version. Since this legal compliance was completed beforehand, the notice issued by the Allahabad High Court to a petition seeking its ban and more recently, a criminal complaint filed with the Panaji Police may appear irregular. But there is a wider pattern and legal precedent that the law frightfully permits.

Process of mandatory pre-certification

Film in India is regulated under the Cinematograph Act, 1952 (“Cinematograph Act”). It establishes the Censor Board of Film Certification (“CBFC”) which certifies films for public exhibition as well as restricted viewing. This process is mandatory, and the exhibition of a movie without what is popularly referred to as a censor board certificate is an offence punishable on conviction with up to three years of imprisonment. Curiously, this legal obligation punishment are prescribed under the Copyright Act, 1957. Additional penalties are also provided in the Cinematograph Act. The High Court of Delhi in Dharmendar Kapoor v. CBFC, 2011 (46) PTC 1 (Del), has also clarified that all cinematographic works exhibited need to certified, even if they are sold only on DVDs for private viewing and are not exhibited in cinemas. In essence, every work featuring moving images, if exhibited even to a restricted audience, even if sold directly and viewed privately, requires mandatory certification.

The criteria for certification is inherently subjective and can lead to arbitrary determinations. The reasons for this are three fold. First, the substantive guidelines for film certification permit subjectivity. They allow allows censorship so that “human sensibilities are not offended by vulgarity, obscenity or depravity” and even of “dual meaning words as obviously cater to baser instincts”. Many more grounds under these certification rules are broadly phrased and do not contain any legal ingredients. Secondly, under Section 3 of the Cinematograph Act, the central government has the complete power to appoint the members of the CBFC, the body making such determinations, censoring movies, and granting exhibition certificates. While a defence that has often been put forward is that the CBFC’s determinations are independent, it is not demonstrated by precedent. Political themes that are inconvenient to the ruling dispensation of the day often meet a higher degree of scrutiny and censorship.

Farcical appeals

Finally, what is the recourse for a film maker unhappy with such a determination? What does one who does not wish to carry out the cuts as demanded by the CBFC do? Such a filmmaker may approach the Film Certification Appellate Tribunal (“FCAT”) which is headed by a retired judge. The FCAT, which appears a strong safeguard in statute, was instituted after the Supreme Court, in K.A. Abbas v. Union of India, (1971) 2 S.C.R. 446, held that mandatory pre-censorship was a valid restriction on the right to freedom of speech and expression under Article 19(1)(a) but then nudged the Union Government to establish an appellate tribunal. Practice has shown however, that the FCAT has been ineffective principally due to the delay and pendency in determining an appeal. Financers of movies are impatient to reap profits and prevent the movie from becoming ‘stale’. Given the capital costs and the commercial stakes involved, filmmakers often grudgingly accept the cuts rather than risk the pendency of an appeal. Also, the mere presence of a retired judge as the chairperson of the FCAT does not guarantee a more liberal reading of the guidelines.

There is ample evidence of both these trends in case law as well as in current events. A recent instance is of the case of Srishti School of Art, Design v. CBFC, W.P. (C) 6806 of 2010, where the High Court of Delhi set aside the order of the appellate tribunal holding, “none of the excisions as directed by the CBFC, three of which have been upheld by the FCAT, are legally sustainable”. In the more recent decision of Krishna Mishra v. CBFC, W.P. (C) 2006 of 2012, the High Court of Bombay found that the FCAT did not even provide any reasons for upholding the CBFC’s demand for cuts. The petitioners victory was pyrrhic because the matter was remanded back to the examining committee of the CBFC for determination. Such a delay would surely cripple a filmmaker financially. A reasonable person would rather make the cuts and release the movie. But then great artists are rarely known to be reasonable.

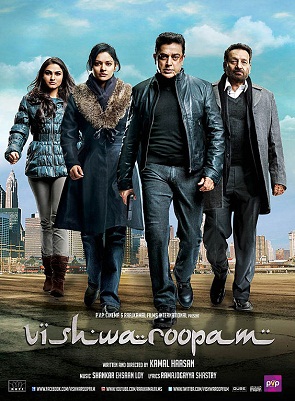

Kamal Hassan’s Vishwaroopam

In 2013, award winning filmmaker Kamal Hassan invested his personal savings and took loans to make the 100 crore film, Vishwaroopam. Shortly before its release, some minority organisations protested its release in the State of Tamil Nadu, which lead to a ban under Section 144 of Code of Criminal Procedure, 1973, citing possible law and order problems. The movie already had a censor board certificate and the Supreme Court had recently, in Prakash Jha v. Union of India, (2011) 8 SCC 372, stated that a state government cannot use law and order as an excuse to prevent the exhibition of a movie by, once the CBFC had certified it.

In 2013, award winning filmmaker Kamal Hassan invested his personal savings and took loans to make the 100 crore film, Vishwaroopam. Shortly before its release, some minority organisations protested its release in the State of Tamil Nadu, which lead to a ban under Section 144 of Code of Criminal Procedure, 1973, citing possible law and order problems. The movie already had a censor board certificate and the Supreme Court had recently, in Prakash Jha v. Union of India, (2011) 8 SCC 372, stated that a state government cannot use law and order as an excuse to prevent the exhibition of a movie by, once the CBFC had certified it.

With the law firmly behind him, Mr. Hassan’s first instinct was to legally fight the ban. Even when the Madras High Court agreed to hear his petition, he effectively lost. Declining him any interim relief, the release of the movie was stayed till the next date of hearing. Finally, a single judge held in his favour, but even that decision was appealed by the state government and the ban was restored. Time was passing and Mr. Hassan was losing money. Things got worse and the ban was extended by other state governments. The movie could not be screened in Andhra Pradesh, Kerala, and Karnataka. It was time to be reasonable. Compromises were made and scissors met the film reel. Remember that at this point, Vishwaroopam had a valid censor board certificate. The additional cuts made to it are the very definition of state coercion. After its release, a wistful Hassan remarked, “I am the son of Socrates. Give me a cup of poison and I will sip it and still speak my freedom”. Far from a Greek philosopher, Hassan was playing the part of Hamlet’s trusted friend Horatio, who was prevented from consuming poison— condemned to suffer misfortune and to live to tell the tale.

The offended and their PILs and FIRs

Clearly, it is not easy to get a CBFC certificate, but even after it has been granted, state governments have at their disposal, a choice of statutory paraphernalia. It doesn’t even end there. Vile gadflies mock offence and approach courts and police stations. Let us first consider public interest litigations (“PILs”) aimed at preventing the screening of movies.

Courts when approached in PILs have repeatedly held that the CBFC is an expert body and that its determinations are generally not open to substantive review on content (as opposed to procedural irregularities). This legal rule is not strictly adopted and there are instances of courts revoking censor board certificates. In most cases even when censor board certificates are upheld, courts do not stay their hands and enter into subjective assessments of the movie in any case. This brings pressure on the movie producer who may again reach a compromise with the court by making cuts. The two rounds of litigation in S. Rangarajan v. P. Jagjivan Ram, 1989 SCC (2) 574, illustrate the tendency of courts to substantially review content. Finally determined by the Supreme Court of India, the case originated from a petition before the Madras High Court, which revoked the CBFC certificate granted to Ore Oru Gramathile (In One Village). The Supreme Court restored it on appeal, permitting the exhibition of the movie. This judgement is celebrated as a victory of freedom of speech, but given that the Supreme Court engages in a review of the content, it rather endangers liberty. It not only discusses the theme of the movie, but each scene the High Court found objectionable. There is a legal discussion of the characters, dialogue, and even the accent in which it is delivered. Such minute examination was later used by courts for making subjective determinations, even after a movie had received a CBFC certificate.

Filmmakers also contend with the risk of criminal complaints and FIRs filed in various corners of the country. These may contain allegations of obscenity, sedition, and defamation. The law with respect to criminalising speech is wide and extensive, permitting legal offence when no factual offence exists. The Supreme Court in Raj Kapoor v. Laxman, 1980 SCR (2) 512, by reading Section 79 of the Indian Penal Code, 1860 with Section 5-A of the Cinematograph Act, has held that such criminal processes against a movie with a CBFC certificate are legally unsustainable. Section 79, akin to a safe harbour protection, provides that nothing is an offence which is done by any person who is justified by law. The law in this context is the Cinematograph Act under which a filmmaker is granted a CBFC certificate. However, while laying down this pronouncement, it Court also held that the accused filmmaker has to participate in the legal process at the trial court and claim a bar under Section 79. There is therefore, no absolute bar. If accused, the filmmaker has to face the pressure of a criminal trial.

Despite Haider’s valid CBFC certificate therefore, Vishal Bhardwaj has formidable legal battles awaiting him at the High Court of Allahabad and the trial court in Panaji. Can we pass it off to coincidence that the Supreme Court remarked in Raza Khan v. State of Uttar Pradesh, SLP (Civ.) No. 31797 of 2010 that “Something is rotten in the State of Denmark, said Shakespeare in Hamlet, and it can similarly be said that something is rotten in the Allahabad High Court, as this case illustrates”.

Despite Haider’s valid CBFC certificate therefore, Vishal Bhardwaj has formidable legal battles awaiting him at the High Court of Allahabad and the trial court in Panaji. Can we pass it off to coincidence that the Supreme Court remarked in Raza Khan v. State of Uttar Pradesh, SLP (Civ.) No. 31797 of 2010 that “Something is rotten in the State of Denmark, said Shakespeare in Hamlet, and it can similarly be said that something is rotten in the Allahabad High Court, as this case illustrates”.

Effects of cinema censorship

Through its exaggerated metaphors and tinted images, cinema can question power with truth. Decades of censorship however, have prevented the cinema of history, politics, and current affairs. The pattern in democratic India has not been different from the colonial era when the Dramatic Performances Act, 1878 was used to ban Nildarpana, a play based on the plight of indigo farmers and Bhakta Vidur became the first movie to be banned under the Cinematograph Act, 1918 because its protagonist resembled M.K. Gandhi.

To prevent financial penury, mainstream cinema has rejected themes which lead to such controversy. Even if these are audience preferences, our legal system has contributed to it. Today, cinema treats us as infants— persons without well-formed thoughts, incapable of deeper introspection. This is what the success of Haider challenges— not its mere financial success but its ability to spark political discussions on issues that require wider introspection such as the morality of a law such as the Armed Forces Special Powers Act, 1958 and of received truths about patriotism. It is this very ability which is being impugned in a court and a police station.

To end, we should fear the censors not merely for preventing movies from release but also for contributing to the apathy of audiences. Today, the audience expects very little from cinema, is accustomed to big budget entertainers, and has lost interest in drama and Shakespeare. It forgets the movie as soon as the credits roll and shrugs off criticism of mainstream movies with, “Hey relax, it’s just a movie”.

(Apar Gupta is a partner at Advani & Co., and was recently named by Forbes India in its list of thirty Indians under thirty years of age for his work in media and technology law.)