Are you familiar with ‘newspeak’? No, not the fictional language from Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four. I am referring to the language beamed across India on television channels every minute. In it, “breast” becomes “chest”, “panties” becomes “pants”, and “beef” becomes “meat”. This display of Victorian sensibility on television is the result of government regulation and private attempts to avoid harsh penalties. Let us examine in detail the regulatory muddle causing this witless display.

Are you familiar with ‘newspeak’? No, not the fictional language from Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four. I am referring to the language beamed across India on television channels every minute. In it, “breast” becomes “chest”, “panties” becomes “pants”, and “beef” becomes “meat”. This display of Victorian sensibility on television is the result of government regulation and private attempts to avoid harsh penalties. Let us examine in detail the regulatory muddle causing this witless display.

Regulating television broadcast

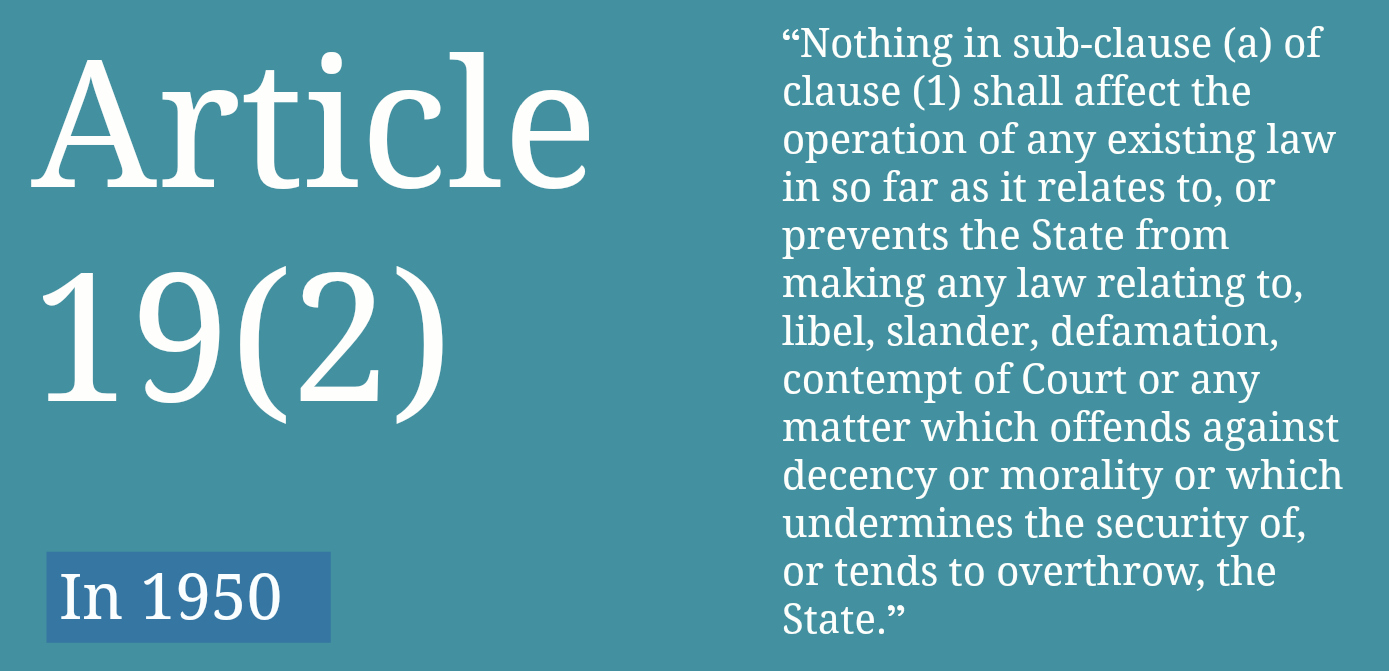

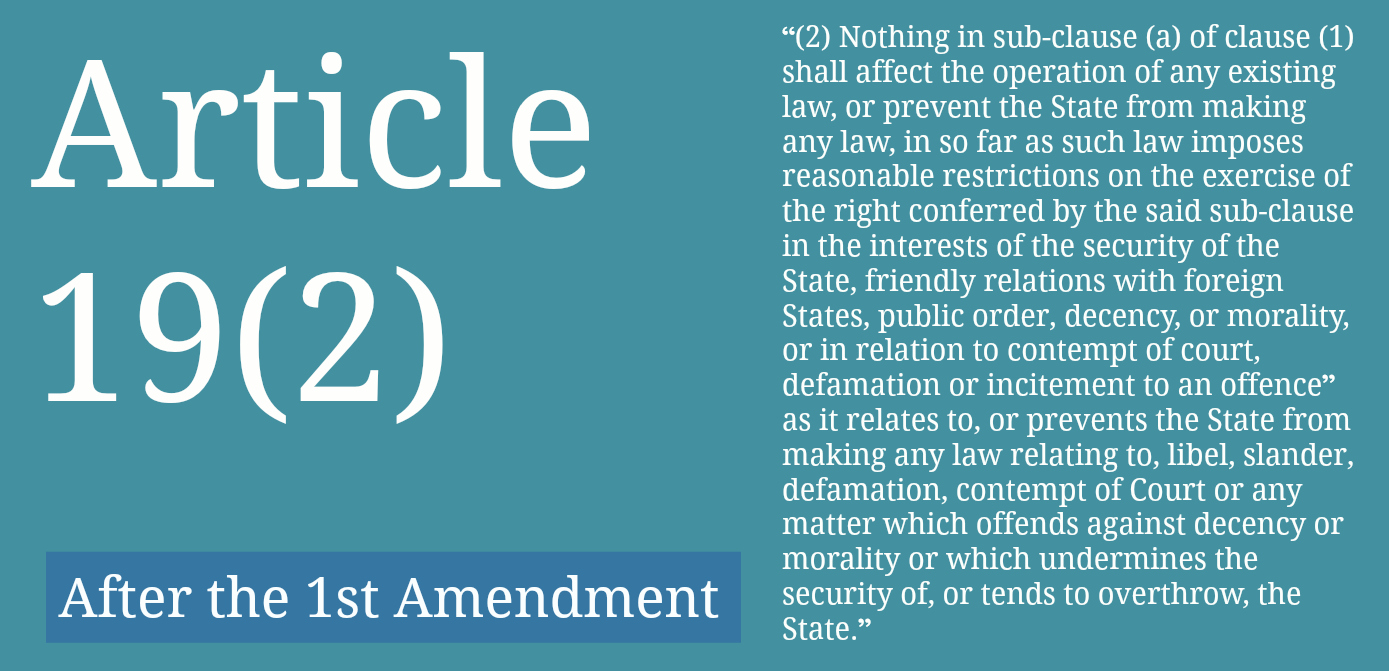

The Cable Television Networks (Regulation) Act, 1995 (“the Act”) was enacted as the principal legislation to govern television channels in India. Section 5 of the Act prepares the ground for content regulation of broadcasts and prohibits telecast of programmes that do not conform to the “prescribed content code”. The Act itself does not define such a “content code”, it has been prescribed in the Cable Television Regulation Rules, 1994, a piece of delegated legislation. Rule 6, popularly called the “Content Code rules”, contains a laundry list of various parameters within which all programme content has to be telecast.

They are vague, generalised, and seek to assuage the hypersensitivity of the most conservative individuals. For instance, it prohibits content that “(i) Criticizes, maligns or slanders any individual in person or certain groups, segments of social, public and moral life of the country;” or, “(k) Denigrates women through the depiction in any manner of the figure of a woman, her form or body or any part thereof in such a way as to have the effect of being indecent, or derogatory to women, or is likely to deprave, corrupt or injure the public morality or morals;”. Such language may appear innocent but becomes nocuous when it has the force of law.

It is also relevant to notice the Policy Guidelines for Uplinking of Television Channels from India, which regulates licenses to television broadcasters to transmit signals from India and the Policy Guidelines for Downlinking of Television Channels to India, which regulates the licenses for transmission to television sets in India (“the policy guidelines”). Both of them contain a chapter titled “Terms and Conditions” that mandates that licensees should comply with the Content Code, failing which licenses for transmission may be rescinded.

Enforcement of television broadcast regulations

What is a right without a remedy? What is a prohibition without a penalty? Both the Act and the policy guidelines prescribe the consequences of breaching the Content Code rules. The Act permits the Union government to prohibit the transmission of any channel or programmefor a prescribed period of time or even permanently. The policyguidelines contain further details including a three-strike clause,under which the nature of the penalty increases upon repeat violations andon the third violation, the government can revoke the license of a television channel.

What is a right without a remedy? What is a prohibition without a penalty? Both the Act and the policy guidelines prescribe the consequences of breaching the Content Code rules. The Act permits the Union government to prohibit the transmission of any channel or programmefor a prescribed period of time or even permanently. The policyguidelines contain further details including a three-strike clause,under which the nature of the penalty increases upon repeat violations andon the third violation, the government can revoke the license of a television channel.

The content code and its penalties are not enforced by an independent regulator but a body of senior bureaucrats called the Inter-Ministerial Group. Chaired by the Secretary of the Ministry of Information and Broadcasting (“the Ministry”), it reviews complaints sent by the public and through another government body, the Electronic Media Monitoring Centre,screens content on television for violations of the Content Code rules. Even if this may sound reasonable in theory, due to the vagaries of the Content Code rules and the harsh penalties for their violation, some peculiar practices have evolved to cause censorship even without the need to revoke the license of a broadcaster.

These practices include the enforcement of extra-legal penalties. A letter from the Ministry to various state governments dated February 19, 2008 states that violations of the Content Code should be dealt with by issuing advisories, warnings, and orders to display apology scrolls. A list of actions or decisions taken for violations of the Content Code between 2004 and March, 2014 lists only 254 cases. Only in 21 out of these 254 cases has the statutory penalty of prohibition of broadcast been imposed. In the remaining 233 cases, despite a specific finding of a violation, the action was either the issuance of an advisory or a warning, or an order to display an apology scroll.

The problem with such an approach is plainly evident. The penalties which are in the nature of advisories, warnings, and orders to display apology scrolls are not prescribed under the Act. They do not have legal force and (at least in theory) do not censure the broadcaster. This may appear to be the benevolence of the State in ensuring freedom of speech but in fact results in the contrary. Legalities are punished and illegalities are conceded.

Such extra-legal penalties are much more harmful for media plurality and content diversity. They allow hypersensitive censors to cut up sentences on the mere apprehension of insensitivity or even criticism.Prior to issuing the warning, advisory, or the direction to run an apology scroll, the private broadcaster is given an opportunity to present their defence. Most often, while presenting such a defence, a private broadcaster submits an apology and seeks pardon for the alleged transgression. This is understandable. In the absence of such deference and self-censure, the penalty may increase from a mere warning to either the prohibition of the telecast of the channel or worse, the cancellation of the license to broadcast.

Such measures, which lack the force of law, also come at the cost of ignoring serious violations for which harsh penalties may be justified. To illustrate, various quiz-based shows make inadequate disclosures about the charges of participation and are designed to dupe viewers. To participate, a viewer has to make a phone call to a number carrying an excessive and expensive per-minute charge (often the pulse duration is even less than thirty seconds). On making such a call, the viewer is placed on hold for several minutes so that the channel earns revenue from the call. Rather than taking any firm action about such dishonest practices, the Ministry, on the receipt of several complaints, merely issued an advisory on September 29, 2011. Expectedly, these quiz shows and the cheating of viewers continues unabated.

Another name for censorship

Self-regulation has more recently been posed as an industry alternative to state censorship. Self-regulation, it has been argued, presents the ideal balance between artistic freedom and cultural sensibilities. Two prominent self-regulatory bodies floated by television channels are, the Broadcast Content Complaints Council (“BCCC”) and the News Broadcasting Standards Authority (“NBSA”). These two organisations havepublished self-regulatory codes and even have an adjudicatory mechanism in place, and through these measures, hope to ensure compliance with the Content code and maintain artistic liberty at the same time. Their results till date, have been questionable.

At a conceptual level itself, the self-regulatory codes have for the first time, put in place a formal content-screening process based on the Act itself. While they may read the law liberally, they do not depart from its fundamental regression. The Content Code remains the basis of prescribed criteria under the self-regulatory guidelines. Content code. It is important to stress that censorship was the Content Code has always been “post-publication”, that is, enforced after the telecast.

Now on the other hand, most television channels formally screen their content through their ‘standard and practices’ departments. That is the reason we are inundated with creative edits to words which may cause offence. Innocuous words such as, “breast”, “sex”, and “virginity” are either bleeped or dubbed over completely. Worse, there are the subtitles that display the word “chest” or a string of stars – “*****” – where the word “breast” should be. This is done devoid of context, for instance, even where the phrase is “breast cancer”. Certainly, even when television channels act as censors, they often replace their scissors with a butcher’s knife.

Other problems persist with self-regulatory censorship. There is a limit to their jurisdiction and reach. The orders of the BCCC and the Indian Broadcasting Foundation are not enforceable in a court of law. Often private compromises are reached and such instances have been documented. Moreover, only a fraction of the channels have become members of such organisations. Out of the 402 general entertainment channels, only 250 are governed by the BCCC. Similarly, out of the 393 news channels registered in India, only 45 are members of the NBSA. There also concerns about a lack of transparency in the publication of complaints and orders. Such concerns need to be addressed through legislation.

Way forward

Recently with a change in government, there has been a push to review existing legislation and policy. The Minister for Information and Broadcasting said on June 7, 2014, that he was in favour of abolishing state regulation. Even though such measures may be excessive, to ensure a modicum of sensibility to content regulation, the following steps are suggested.

Recently with a change in government, there has been a push to review existing legislation and policy. The Minister for Information and Broadcasting said on June 7, 2014, that he was in favour of abolishing state regulation. Even though such measures may be excessive, to ensure a modicum of sensibility to content regulation, the following steps are suggested.

The self-regulatory organisations to their credit, have not acted merely as bodies to limit the harsh penalties under the Cable Television Networks Act. They have in the past requested for a system of co-regulation, in which a legislation grants them statutory recognition and aids in curing the legal deficiencies that exist. They recognise that at present, they are at best a stop-gap arrangement.The longer such an ad-hoc system continues, the more damage there will be to artistic freedom and freedom of speech.

We also need to look beyond the regressive content code. Any content regulation must place an emphasis on context and censorship has to be proportional to the end that is sought to be achieved. An easy alternative is to link the content code to existing penal provisions. For instance, rather than prohibiting, “criticism of individuals”, a reference may be made to Section 499 of the Indian Penal Code, 1860 containing the offence of defamation. Even though such provisions may be regressive, theyat least have legal ingredients that have been refined by court rulings. Moreover, the present system of overbroad censorship, often caused by broadly defined categories under the Content Code, will abate. Most offences contain precise definitions and legal ingredients which can be applied more easily and in a limited manner by the television channels.

Finally, any legal reform must appreciate the role of the public as not only having the right to complain against offensive content but also the right to view it. Hence, the element of public injury which permits complaints, needs to ensure a system of transparency and pro-active disclosures. Any censorship which is caused, either by private self-regulatory bodies or by the government, needs to be disclosed and published. Moreover, even third parties should be permitted to file legal challenges against any censure. Such a remedy would add teeth to the right to view and receive information which has been recognised to be part of the freedom of speech and expression and is even recognised in cases of censorship of books and written materials.

These solutions would merely be the beginning. The more fundamental question that has to be answered with courage and honesty is to what extent law should censor television broadcasts. If we shirk away any longer, we may continue being governed by a content code which restrains breast cancer awareness programming but permits sensationalist news broadcasts about young women drinking in pubs.

Apar Gupta is a partner at Advani & Co., and was recently named by Forbes India in its list of thirty Indians under thirty years of age for his work in media and technology law.