Joel Stein’s article (My Own Private India, July 5) in Time magazine was insensitive. But it is important to distinguish the insensitive portions of his column from its unfunny clichés. In his column, Stein lamented how his hometown in Edison, New Jersey, had become “a maze of charmless Indian strip malls and housing developments”. The article sparked outrage at home and abroad, and Time magazine eventually did “regret” that readers took offence. However, as a community, Indians have often been accused of being “oversensitive”, perhaps justifiably so. For this reason, it is important in this instance to identify the real reason why Joel Stein’s July 5 article in Time magazine was insensitive.

Comedy is society’s safety valve and comedians, like the court jesters of old who criticised kings with impunity, serve an invaluable function in any system which accords deference to the freedom of speech and expression. But there were two references in Stein’s article which had absolutely no redeeming comedic or informative virtue.

The first instance was when Stein flippantly mentioned the term “dot heads” in his column, evoking painful memories of the “dotbusters” racism of the late 1980s which Indian Americans, especially those living in New Jersey, had to painfully endure. Hate speech, though legal in America, is offensive. If no credible news establishment can get away today with calling an African American the “n” word, or espousing pro-holocaust rhetoric, then one wonders how a reputable magazine could get away with referring to Indian Americans as “dot heads”, even if the historic wounds were not as deep. Stein’s words were reminiscent of the racist tirade at a bar not so long ago by Seinfeld’s Kramer, Michael Richards, who lost his comedic credibility ever since.

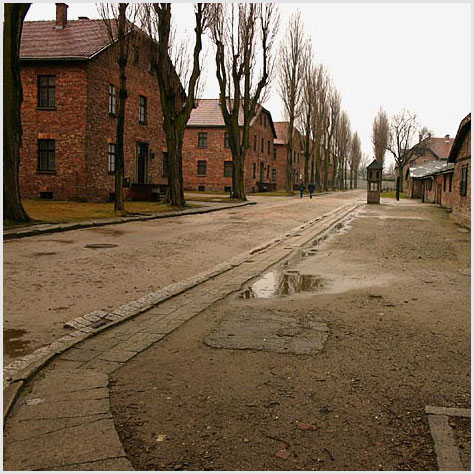

The second instance where Stein perhaps crossed the line, although to a lesser extent, was when he spoke of “why India is so damn poor”. For a moment, let’s forget that India is “so damn poor” not because of our “not-so-bright cousins” as he claimed, but because of centuries of colonial oppression which we fought with peace, not war. But ridiculing poverty, in a country where malnourished children die of starvation and debt-ridden farmers commit suicide, was distasteful, perhaps bordering on insensitivity to human suffering.

That having been said, there were other allusions to Indian stereotypes in the piece, which were not offensive, and should not be considered so, although Stein’s comedic abilities may be questionable. For example, serious offence was taken by some to his reference to “gods with multiple arms” and “an elephant nose”. This statement, while unfunny (and perhaps clichéd), is inoffensive.

There are numerous examples in popular culture where divine symbols, belonging to various cultures, have been poked fun at, hilariously. Michael Scott’s faux-pas in a hilarious episode of The Office when he mistakes the story of Diwali for the Lord of the Rings; and the numerous stabs at religious figures on shows like Family Guy and South Park are good examples. Perhaps Stein’s column gives us reason to introspect, and realise that our holy symbols, religious or otherwise, do not diminish in stature merely because somebody ridicules them, however distastefully. Our symbols, and certainly our Gods, are made of stronger stuff.

But most importantly, we need to distinguish that which we find offensive, from that which we don’t find funny.

Our tolerance to comedic representations of the Indian community has arguably improved over the years: there was time when we denounced Peter Sellers, but today we applaud Russell Peters. Some, (not all) reactions to Stein’s article tend to demonstrate that we do, at times, tend to take ourselves a little too seriously. Stein’s piece is in places replete with self-deprecating humour (allusions to “stupid Americans”, “the A&P I shoplifted from”, “the Italian restaurant that my friends stole cash from”, “an entire generation of white children … with nowhere to learn crime”). So it is important for us to understand where he crossed the line.

Regrettably, in the immediate aftermath of the article in Time magazine, the Indian blogosphere took to racially abusing Joel Stein, and his community. It would certainly be hypocrisy on our parts to denounce insensitivity, with more insensitivity. A famous American judge, Louis Brandeis, had once said that falsehood must be addressed with “more speech, not enforced silence”. If this is true, then rather that answering racism with more racism, shouldn’t bad humour be addressed with better humour?

So here goes: what was Joel Stein doing on Christmas Eve? Unlike Elena Kagan, he was at an Indian restaurant in his hometown in Edison, New Jersey.

(By Abhinav Chandrachud, who graduated last year from the Harvard Law School, is a lawyer in Los Angeles.)

The views expressed are personal.

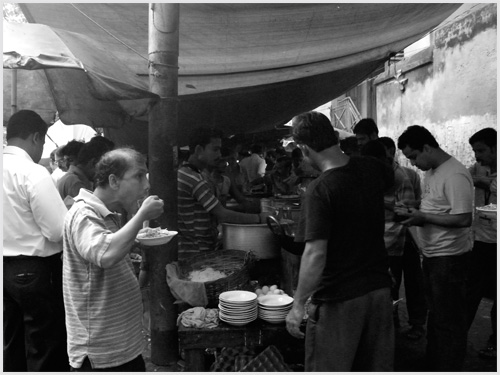

This place in the High Court chattar (locality) is a favourite with anyone interested in a quick, inexpensive lunch. Junior attorneys are often seen carrying packets of food from here for their friends.

This place in the High Court chattar (locality) is a favourite with anyone interested in a quick, inexpensive lunch. Junior attorneys are often seen carrying packets of food from here for their friends. Located next to Victor Moses, one of Calcutta’s oldest firms, this shop is known for excellent jalebis.

Located next to Victor Moses, one of Calcutta’s oldest firms, this shop is known for excellent jalebis. Mughal Garden is the new kid on the block, and unlike most others in the vicinity that serve the usual rice and fish combination, this place is famous for its, yes, Mughlai food.

Mughal Garden is the new kid on the block, and unlike most others in the vicinity that serve the usual rice and fish combination, this place is famous for its, yes, Mughlai food.