Mukul Rohatgi, the Attorney General for India, reportedly said during proceedings before the Supreme Court that the collegium had appointed many undeserving and inefficient judges to the apex court and high courts who went on to “create havoc” in the country. To argue that it was a myth that only judges could appoint good judges, he submitted in a closed envelope, a list of eight cases of what he called “bad appointments and selection” and referred to the questionable conduct of many judges.

Mukul Rohatgi, the Attorney General for India, reportedly said during proceedings before the Supreme Court that the collegium had appointed many undeserving and inefficient judges to the apex court and high courts who went on to “create havoc” in the country. To argue that it was a myth that only judges could appoint good judges, he submitted in a closed envelope, a list of eight cases of what he called “bad appointments and selection” and referred to the questionable conduct of many judges.

Can proceedings be initiated against the Attorney General for these statements bordering on defamation? Do the affected lot have a remedy?

“In many settings, if we called someone a liar, cheat or incompetent or worse, we might be on the receiving end of a defamation claim. If we need to say that during litigation, we’re generally protected by the litigation privilege. The litigation privilege confers absolute immunity from defamation claims for statements made during both judicial and quasi-judicial administrative proceedings. The privilege applies to attorneys, parties, judges and witnesses. To qualify for such privilege, the statement must meet two general tests. First, it must have some reference to the subject matter of the litigation. Second, it must be made in connection with a judicial proceeding.”

This is the statement of law from American Jurisprudence. The privilege is traceable to the “public policy of securing to attorneys as officers of the court, the utmost freedom in their efforts to secure justice for their clients”. The privilege therefore, is absolute.

But for a subtle change made by the House of Lords recently in Arthur J.S Hall and Co. v. Simons, the British precedent would have been identical. Attorneys continue to enjoy absolute immunity in addressing courts during the proceedings from being sued either in civil law or under the criminal dispensation, but this case removed the immunity enjoyed by advocates from being sued for ‘negligence’.

Defended against a civil claim – many Madras High Court decisions

Closer home, on January 1, 1800, the legendary Eardley Norton was sued by Sullivan, a member of Madras Civil Service for defamatory conduct in addressing the members of the jury in a criminal trial. A full bench of five judges of the Madras High Court ruled that Norton enjoyed

absolute privilege from being sued in civil law for damages. In the absence of proof that Norton was actuated by malice and because the allegedly defamatory utterance was not alien or irrelevant to the matter in inquiry, the High Court accepted Norton’s defence, “I acted under my instructions: all I said and did was within the four corners of those instructions and my duty to my client compelled me to say what I said”.

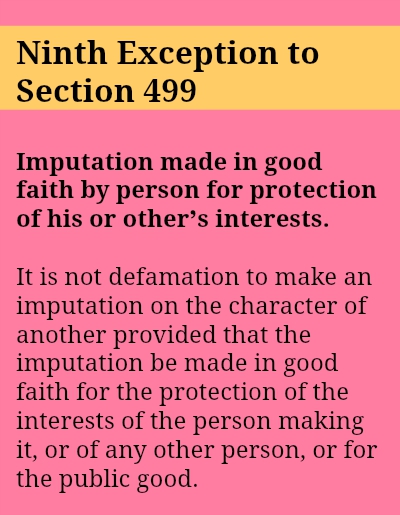

On December 2, 1926, the Madras High Court relied on Sullivan v. Norton and decisions from the Bombay and Calcutta High Courts in Thiruvengada Mudali v. Thirupura Sundari Ammal and ruled that when the statement imputed with defamatory content was made in the course of a necessary line of submission to aid the cause of a client, then even the presence of malice will not override the presumption of good faith. Advocates who have been accused of defamatory conduct are also protected by the Bombay High Court’s decision in Navin Parekh v. Madhubala Shridhar Sharma, which in fact relied on the ninth exception to Section 499 of the Indian Penal Code, 1860.

When “imputation was made in good faith (which is always presumed) for the protection of interest of the person making it, or of any other person, or for the public good”, then such utterance would not amount to defamation. In February 2008, the Madurai Bench of the Madras High Court again rescued an advocate from facing criminal prosecution for allegedly making defamatory statements in the course of pleadings in a suit for partition.

A thinner defence against criminal defamation

A thinner defence against criminal defamation

All may not be lost for persons affected by such submissions. In its decision in Sanjay Mishra in March 2012, the Delhi High Court drew a subtle distinction between English and Indian law.

While in England, there is total immunity for a counsel for such conduct from being proceeded against either for damages in a civil action or under criminal law, that level of protection os confined to a civil action alone in India. Under the criminal law of defamation, the ninth exception to Section 499 actually enables parties to sue a counsel if they can demonstrate malice or a lack of good faith in the utterance or conduct. That, however, is too thin a line, especially in a case of the kind that the Attorney General was arguing – a one-off case, where the submissions were not too alien either.

Vijayaraghavan Narasimhan is an advocate practicing at the Madras High Court.