It helps to occasionally step back and seek the true meaning of an element of procedure. This is true about the framing of issues in a civil suit since the significance of this step in a trial is often taken for granted.

It helps to occasionally step back and seek the true meaning of an element of procedure. This is true about the framing of issues in a civil suit since the significance of this step in a trial is often taken for granted.

What is an issue?

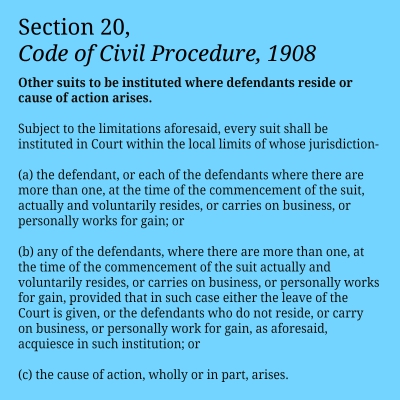

The title of Order 14 of the Code of Civil Procedure, 1908 (“CPC”) is “Settlement of Issues and Determination of Suit on Issues of Law or on Issues Agreed Upon”. Clearly, a suit is determined on the basis of issues of law or other issues agreed upon by the parties in a suit. But what is an “issue”? Although the CPC does not define the term, Sub-rule 1 of Rule 1 of Order 14 says that issues arise when a material proposition of fact or law is affirmed by one party and denied by the other. In other words, both parties must disagree on a material proposition of fact or law.

The Evidence Act, 1872 also defines “Facts in issue” to mean and include any fact which, either by itself or in connection with other facts, has a bearing on a right or liability asserted or denied in a suit. According to the explanation to this definition, when a court records an issue of fact under the CPC, the fact to be asserted or denied in response to such an issue would also be treated as a fact in issue.

What is a material proposition giving rise to an issue? Sub-rule 2 of Rule 1 states that material propositions are those propositions of law or facts which a plaintiff must allege in order to show a right to sue or a defendant must allege in order to constitute a defence. Simply put, a material proposition is one that advances a party’s case factually or legally.

Sub-rule 3 mandates that each material proposition on which the parties disagree shall be framed as a distinct issue. Could it be said therefore, that propositions of fact or law which do not further a party’s case are not material and therefore ought not to be framed as issues? What consequences follow when a proposition of fact or law, although material, is not framed as an issue despite the parties being at variance with each other?

On this, the Supreme Court has held that the non-framing of an issue does not vitiate the proceedings as long as the pleadings of parties bear out that the issue exists and both parties have led evidence at trial to prove their respective contentions on the issue. In other words, a court can rule on an issue even if it has not been specifically framed, so long as it is material to the determination of the suit.

The process of framing

How does a court go about framing an issue? Sub-rule 5 of Rule 1 lays down the procedure for this. At the first hearing of a suit, the court shall, after reading the plaint and the written statement, and after examination under Order 10 Rule 2, and after hearing the parties or their counsel, ascertain upon what material propositions of fact or law the parties are at variance, and shall then proceed to frame and record the issues on which the right decision of the case appears to depend.

What does this mean? Simply, that a court has to understand the contentions of the parties from their written pleadings and oral submissions and distill only those propositions of fact and law on which the parties differ and which are “material” for the adjudication of the suit. The question of materiality in Sub-rule 5 has no bearing on the tenability of the contentions of parties on factual or legal propositions. It simply refers to testing an issue for its relevance to the determination of the case.

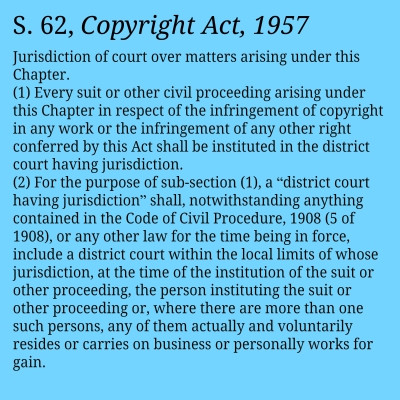

For instance, in a suit for patent infringement, if there is no dispute between the parties about the plaintiff’s ownership of the patent, there is no point in framing an issue on it. Even though the question of ownership is material, the parties do not disagree on it. Contrast this with a situation where the plaintiff claims to be an assignee of the erstwhile patent owner and the defendant disputes the fact of assignment. The question of ownership or assignment of the patent is material because under the Patents Act, only a patentee or the exclusive licensee may institute a suit for infringement. In other words, the maintainability of the plaintiff’s action is in question. Moreover, since the parties disagree on this material question, the court has to frame an issue on it.

This procedure of framing of an issue needs to be clearly understood. Some people tend to read more into the mere framing of an issue under Order 14 than is warranted. The framing of an issue does not amount to a court taking a position on the contentions of the parties on a material question of fact or law. The court is merely etching the contours of the trial so that the progress of the trial is not waylaid by a slugfest on immaterial issues that have no bearing on the adjudication of the rights and liabilities of the parties. Reading the Supreme Court’s decision in Makhanlal Bangal v. Manas Bhunia (2001), delivered in the context of the Representation of the People Act, 1951, but relevant since the procedure under the CPC applies to the statute, will help clear the fog around the framing of issues.

In the next post, I will deal with the commencement of trial.

Sai Deepak is an engineer-turned-law firm partner-turned-arguing counsel. Sai is the founder of Law Chambers of J. Sai Deepak and appears primarily before the High Court of Delhi and the Supreme Court of India. He is @jsaideepak on Twitter and is the founder of the blawg “The Demanding Mistress” where he writes on economic laws, litigation, and policy. All opinions expressed here are academic and personal.