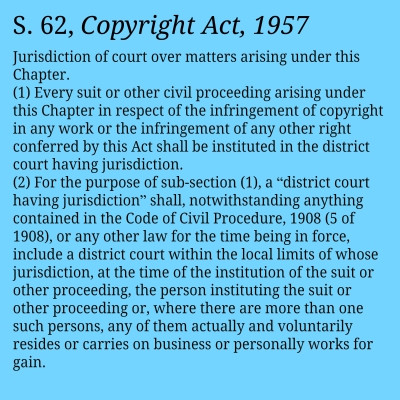

A plain reading of Section 62 of the Copyright Act, 1957 will reveal that Section 62(2) of the Copyright Act is an exception to the general rule vesting jurisdiction in a civil court in case of ‘infringement of copyright in any work’.

A plain reading of Section 62 of the Copyright Act, 1957 will reveal that Section 62(2) of the Copyright Act is an exception to the general rule vesting jurisdiction in a civil court in case of ‘infringement of copyright in any work’.

Under Section 62(1), such a suit has to be instituted before ‘the district court having jurisdiction’ in respect of the ‘infringement of copyright in any work’.

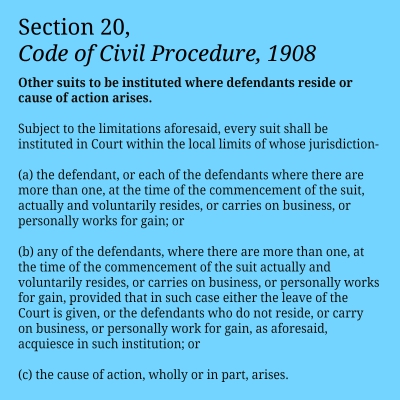

The general rule, seen in Section 20 of the Code of Civil Procedure, 1908 (“CPC”), is that a civil proceeding complaining of ‘infringement’ has to be instituted where the ‘cause of action’, that is, the ‘infringement’ arose, or where the defendants reside or carry on business.

Section 62(2), however, has a non obstante clause vis-a-vis Section 20 of the CPC and any other law in force. Therefore, only Section 62 is invoked to determine whether such a suit is territorially tenable.

Section 62(2) thus makes an exception to Section 62(1). It means that a ‘district court within whose jurisdiction plaintiff resides or carries on business’ is also a place of permissible jurisdiction. This necessarily means that even if the ‘infringement of copyright in a work’ arose within the jurisdiction of Court A, the suit can be filed by the plaintiff in Court B, within whose jurisdiction he resides or carries on business.

Once the plaintiff proves that he was residing at the chosen venue or he was carrying on business there, he can surely sue at that location. The plaintiff need only show that he was ‘actually and voluntarily residing’ there or ‘carrying on business’ or personally working for gain. Once these ingredients are satisfied, the suit has to be held maintainable. In effect, the criteria under Section 20 of the CPC, that is, where the ‘cause of action’ arose or where the ‘defendant was residing’ or ‘carrying on business’ are rendered otiose.

The reasoning behind creating this exception was that an artist must have total control and dominance over his ‘copyright in a work’. The artist has the right to carry his right to sue wherever the artist resides or moves to reside or carries on business or moves to carry on business, irrespective of where the cause of action or infringement arises. It is a clear and lucid departure from the ordinary rule of territorial jurisdiction.

How Sanjay Dalia rewrote the Copyright Act, all in the name of “purpose”

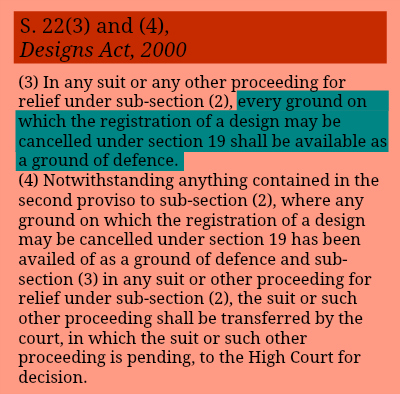

Unfortunately, in one more exhibition of the ‘purposive interpretation’ rule, the Supreme Court has affirmed the decision of the Delhi High Court in Indian Performing Rights Society Ltd. v. Sanjay Dalia.

The plaintiff was carrying on business through a branch office in Delhi though their head office was in Mumbai. The alleged ‘infringement’ had taken place in Mumbai. The concurrent findings of the Delhi High Court declining to entertain the suit in Delhi was affirmed by the top court.

“In our opinion, the provisions of section 62 of the Copyright Act and section 134 of the Trade Marks Act have to be interpreted in the purposive manner. No doubt about it that a suit can be filed by the plaintiff at a place where he is residing or carrying on business or personally works for gain. He need not travel to file a suit to a place where defendant is residing or cause of action wholly or in part arises. However, if the plaintiff is residing or carrying on business etc. at a place where cause of action, wholly or in part, has also arisen, he has to file a suit at that place, as discussed above.”

‘Purposivism’ and ‘consequentialism’ cannot be used to tide over the ‘convenience or inconvenience’ of parties. When the Parliament has conferred on the plaintiff, the right to sue for infringement wherever he resides or carries on business, is the Supreme Court right in concluding that plaintiff could not do so in a case where the infringement arose in Mumbai and defendant carried on business in Mumbai and plaintiff also had its head office? This amounts to re-writing the legislation. Oh, for an Antonin Scalia dissent of the Obamacare and Obergeleff genre.

Vijayaraghavan Narasimhan is an advocate practicing at the Madras High Court.