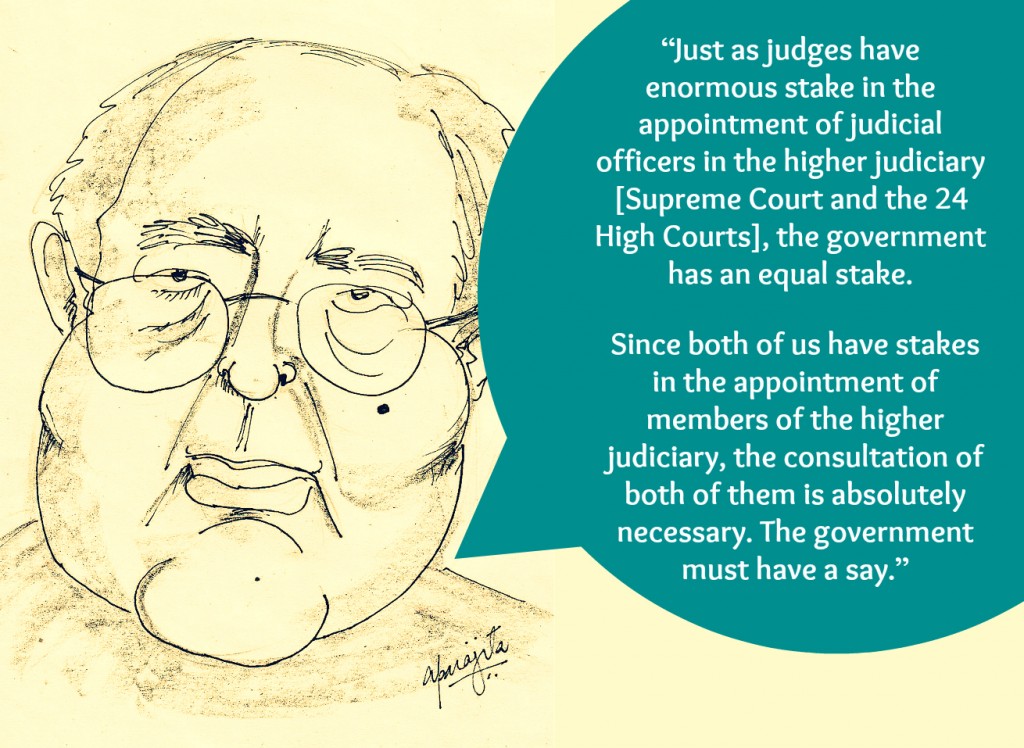

The debate about who should appoint judges to the higher judiciary is back on the table. The independence of the judiciary is a key question in our democracy and I think it was the Union Minister of Law and Justice, Kapil Sibal, who put it back there. The Hindu quotes him arguing for a voice for the executive in the appointment of judges.

This elicited some response from the Bar. Anil Divan, the President of the Bar Association of India, criticised the secrecy surrounding the Judicial Appointments Commission Bill and argued that Mr. Sibal’s proposal sought to recapture the executive’s primacy in judicial appointments.

The Bar Council of India also wanted in.

“… the BCI as well as state bar councils are also feeling that in the matter of appointments of High Court and SC judges, the bars should also have a say and the concerned bar should also be taken into confidence before the recommendations of names for the appointments.”

So it is not the best piece of drafting, but it is quite clear that the Bar Council of India was angling for representation on the proposed National Judicial Commission.

National Judicial Commission?

We’ll get there soon.

Okay, what’s the “collegium system”?

All appointments to the higher judiciary are made by the President of India. The President and the Union executive that the President’s office represents however, have almost no say in these appointments. The choice is made by a collegium of the most senior judges headed by the Chief Justice of India. If the appointment has to be made to a particular High Court, then senior judges of that High Court are also represented in the collegium.

Once this collegium recommends a name to the President of India, the appointment has to be made. The only influence that the executive of the Union or any of the states can bring to bear on the appointments process is by forwarding material relevant to the choice of a potential judge to the collegium. The collegium however, need not pay heed to the executive.

Woah! That sounds an awful lot like judges appointing judges. How did that happen?

During the last two decades of the previous century, the Indian judiciary appropriated for itself the right to appoint judges to the higher judiciary.

See the following extract from Article 124 of the Constitution of India.

“Every Judge of the Supreme Court shall be appointed by the President by warrant under his hand and seal after consultation with such of the Judges of the Supreme Court and the High Courts in the States as the President may deem necessary for the purpose and shall hold office until he attains the age of sixty-five years:

Provided that in the case of appointment of a Judge other than the Chief Justice, the Chief Justice of India shall always be consulted:”

On a plain reading of this provision, the power to appoint judges to the Supreme Court of India is clearly vested in the President of India. After the third judgment in 1998 however, this provision and Article 217, which deals with the appointment of judges to the High Courts, had been interpreted by the Supreme Court of India to mean the collegium system.

Read the three judges cases on Indiankanoon:

S.P. Gupta v. President of India and Others (1981)

Supreme Court Advocates-on-Record Association and Another v. Union of India (1993)

While it was the culmination of the judiciary’s assertion of independence after some of the excesses of Indira Gandhi’s regime, the use of the collegium system to appoint judges has coincided with a period of increased focus on corruption and the lack of transparency in the judiciary. Mr. Diwan’s column provides more historical context to the current debate.

Leaving aside questions about exceeding the judicial brief, what is the alternative to the “collegium system”?

The National Commission for Review of the Working of the Constitution (“NCRWC“), which submitted its report in 2002, had recommended the establishment of a National Judicial Commission to make appointments to the higher judiciary.

You can watch Mumbai-based Senior Advocate Iqbal Chagla endorse the National Judicial Commission proposal in this video. His argument is that the collegium system places too much faith in the individuals at the top of the judiciary. Justice Krishna Iyer calls the system “outrageous” here because of the scope it allows for favouritsm and its lack of emphasis on a thorough investigation into the antecedents and social philosophy of a judge. The former Chief Justice of India, P.N. Bhagwati, says here, that he is opposed to the collegium system because it often leads to bargaining.

According to the NCRWC, the National Judicial Commission would have the Chief Justice of India as its Chairman and two of the senior most judges of the Supreme Court, the Union Minister for Law and Justice, and an eminent person appointed by the President after consulting with the Chief Justice of India, as its Members.

Are there other opinions about the constitution of the National Judicial Commission?

In the video linked above, Mr. Chagla acknowledged the “vexed” nature of the question about what the constitution of the National Judicial Commission should be, but suggested that it should comprise the Chief Justice of India, the Chief Justice of any other court, eminent lawyers, the Leader of the House, and the Leader of the Opposition. The latest missives from Mr. Sibal and the Bar Council of India argue for representation from the Union executive and the relevant Bar in the National Judicial Commission.

There is another opinion though, and Mr. Chagla refers to it later in the video — that the question of who will be part of the National Judicial Commission is not as important as accepting the principle of it. I think Sriram Panchu expressed it best.

“But the important thing is not the composition of the Commission. As important as it is, it is also the processes being followed. Today, I put my faith more in processes than in people.”

(Aju John is part of the faculty on myLaw.net.)