Not many of you are familiar with this travesty (Malayalam link) yet. That is a circular from the Department of Local Self-Government of the Government of Kerala signed by its Principal Secretary. It encourages marriage registrars to register Muslim marriages even where the groom is less than 21 years of age or the bride is less than 18 (but older than 16) years of age, as long as (ha!) the marriage had the approval of the guardians of the bride and the groom. Quite predictably, the circular has raised a stink. See here, here, and here.

How dumb is the Department of Local Self-Government?

Did the Department not know that it was encouraging marriage registrars to commit a crime? If they did not, the Department’s pretty stupid because it is pretty clear that it is a crime for a male over the age of 18 to be the groom in a child marriage and for any person to perform, conduct, direct, or abet a child marriage.

Under the Prohibition of Child Marriage Act, 2006, a “child marriage” is one where either the groom has not completed 21 years of age or the bride has not completed 18 years of age.

– Under Section 9, a male adult who contracts a child marriage can be punished with rigorous imprisonment up to two years or a fine of up to one lakh rupees or both.

– Performing, conducting, directing, or abetting a child marriage are made punishable with the same penalties by Section 10.

– Similarly, Section 11 of the Act, a person (including parents and guardians) with charge of a child in a child marriage who does anything to promote the marriage or negligently fails to prevent it from being solemnised, can be punished with the same penalty. There is even a presumption that a person in charge of a child who has contracted a child marriage had negligently failed to prevent its solemnisation.

Suspecting the Department’s intelligence is obviously the more charitable view. If the Department knew that the acts above were crimes, we have to come to the view that the circular is a local revolt against the policy behind the Prohibition of Child Marriage Act, 2006.

How dumb does the Department think we are?

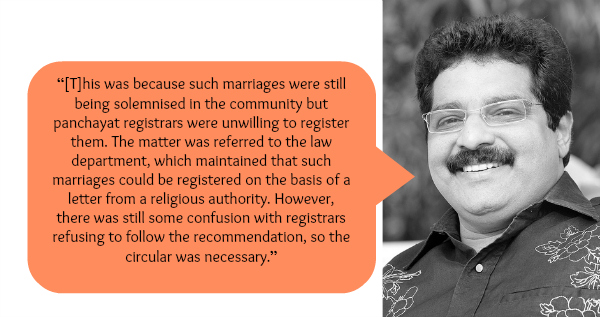

M.K. Muneer of the Indian Union Muslim League, the minister who also holds charge of the Department of Local Self-Government, tried to justify the promotion of child marriages.

Mr. Muneer’s statement followed a bit of disingenuity in the circular itself. It reasoned that the circular was appropriate because the Muslim personal law did not require that the groom have attained the age of 21 and that bride have attained the age of 18 and that the Prohibition of Child Marriage Act did not declare such marriages void.

That the Muslim personal law does not set an age requirement for the validity of a marriage has no relation to the definition of the crimes under Sections 9, 10, and 11 of the Prohibition of Child Marriage Act. The marriage may be valid but that need not stop the police from proceeding against those who have committed actions amounting to those crimes. The Prohibition of Child Marriage Act does not declare child marriages void but that is not because of any confusion about its policy on child marriage. The Act preserves the rights of the parties to the child marriage and those of the children born out of such marriages.

Section 3 however, declares that such marriages are voidable at the option of the party who had been a child at the time of the marriage. Such a person can file a petition in the district court, before attaining two years of majority, to declare the marriage void. The circular therefore, was quite clearly insincere in its selective appreciation of the Prohibition of Child Marriage Act and Registrars would be quite right to cite a fear prison time to not register such marriages.

(Aju John is part of the faculty at myLaw.net.)