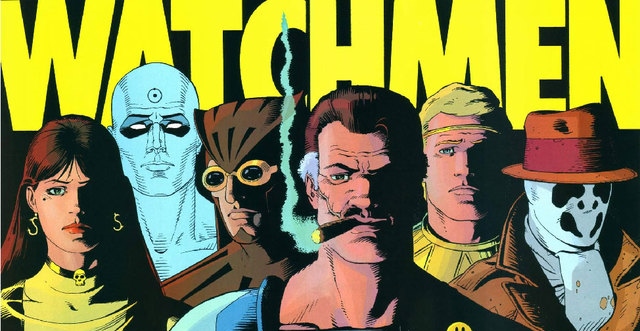

In September, 1986, when the first issue of a comic book miniseries called Watchmen hit the stands in the US, no one was really quite ready for it. Although he had already begun garnering respect in the comic book industry, Alan Moore was not yet the household name he is today, and his grim vision of the usually bright, cheerful and simplistic good-triumphs-over-evil world of superheroes was completely unprecedented. Of course, by now everyone with any interest in pop culture has at least heard of the Watchmen series. It is now considered a seminal work in not just the comic industry, but also in the world of English literature at large: in 2005, Time magazine included it in its list of the “All-Time 100 Greatest Novels”, the only graphic novel to be given that honour, and in 2009, against Alan Moore’s wishes, it was made into a major blockbuster by Zack Snyder.

Alan Moore

It seems Alan Moore initially got the idea for Watchmen from a famous Latin phrase: “Quis custodiet ipsos custodes?” which can be literally translated to “Who will guard the guards themselves?”, or, more famously, “Who watches the watchmen?” (which also became the popular tagline for the series as well as the movie). The phrase is often attributed to Plato, because it just seems like something he would have said in the Republic whilst waxing eloquent on the nature of power and its corrupting influence on people who have it. But these words were not Plato’s, and the phrase has been taken out of context and given a deeper, more philosophical meaning than was originally intended.

At some point towards the end of the 1st century AD (or towards the beginning of the 2nd century AD; no one’s really sure), Juvenal, a Roman poet we know almost nothing about, wrote a collection of poems called the Satires. It included a poem which was quite unequivocally misogynistic, ruminating on women’s innate tendencies towards “immoral behaviour” and men’s inability to control it. The phrase comes from the following lines:

I know

the plan that my friends always advise me to adopt:

“Bolt her in, constrain her!” But who can watch

the watchmen? They keep quiet about the girl’s

secrets and get her as their payment; everyone hushes it up.

Juvenal

What Watchmen, and the phrase it originates from, illustrate starkly is the fact that things are not as they seem on the surface; culturally/historically accepted and defined “truths” are often unreliable. Watchmen was Alan Moore’s deconstruction of the superhero myth in real-world terms – where he explored the possibility that under the shiny, awe-inspiring surface, beings with godlike powers could be flawed, capricious, disturbed, violent and sociopathic individuals. The superhero as a noble, selfless force for good was a cultural monolith, seldom questioned as a trope. Alan Moore decided to question that one-dimensional viewpoint, and the result was a masterpiece. On a different level, the present use of “Who watches the watchmen” is in itself an example of how words can be de-contextualised and given a different, more socio-culturally acceptable meaning. It tells us that constant deconstruction and analysis is the very least of our responsibilities as thinking, rational beings.

My long-winded and clumsily constructed arguments above have a point, and I should really get to it.

On June 17, 2013, the Hindu ran a now (in)famous article on the now (in)famous order of the Madras High Court, stating unequivocally that the court had proclaimed that if an unmarried couple have sex, they will be considered married. The lack of a nuanced and balanced approach in the piece clearly showed that the reporter hadn’t spent too much time on reading and understanding the order and its context. Within a few hours, a number of articles criticising the Hindu’s simplistic coverage of the complex issue appeared all over the internet. However, by that time social media websites had already exploded with misplaced outrage and more than a few inappropriate jokes. Of course other news sites had also run similar stories, but The Hindu commands a certain degree of respect, even among its detractors, for its high standards of reportage and journalism – misunderstanding an issue isn’t usually a charge levelled against it. Fortunately, we live in an age in which information is readily available and can be disseminated within seconds. Public opinion which, for a while, was positioned strongly against the order is now balancing out as a more reasoned and informed discourse unfolds. The mainstream media stands as a source of factual information and is, by extension, regarded as a purveyor of truth. Here is another historical monolith on which society leans. This is not unreasonable given that searching for the truth and presenting it to the people has been the media’s fundamental function. But recent history has taught us that the media isn’t above selling news space, taking editorial mandates from large corporate investors, blurring the line between reportage and opinion, sensationalising the news through hyperbole and using questionable techniques to get a story. Now, for the consumer of mass media, the “truth” has become a far more complicated and difficult thing to get to.

It is clear now that the Madras High Court’s decision is quite progressive on women’s rights and reverses an extremely egregious order of the lower court. However, I used the term “misplaced outrage” earlier, because there should be outrage at how the Madras High Court seems to think that the only significant indicator of a marriage is sex. And if that isn’t the intention of the order, there should be outrage at how badly and dangerously the decision is worded. The Madras High Court has defended the order stating that it “protected Indian culture and welfare of women.” The biggest monolith in this case is this “Indian culture” that the court has tried so earnestly to protect – this vast, ethereal, omnipotent, nebulous thing which keeps floating in and out of our consciousness, this undefined entity which is powerful enough to unite a billion people, but so fragile that it needs protection at every moment, especially from the “sinful evil” of the west. “Indian culture” is apparently an intractable monolith that refuses to move with the times. It is formless, but alive. It is whatever a few old, conservative and powerful people say it is. And if they are to be believed, every time consenting adults want to have sex outside wedlock, or women wear skirts instead of saris, or you listen to pop music, it has a massive heart attack.

In India, both the media and the judiciary have a proud history of acting as society’s watchdogs. In their own ways, both constantly endeavour to get to the truth. But they are not infallible. It is essential for the citizens of a democracy to think for themselves, look at an issue from every perspective, get all the facts straight, listen to every argument and form an informed and intelligent opinion. Who watches the watchdogs? We do. It’s up to us to ensure that the pillars of democracy never become monoliths.

(Sayak Dasgupta wanders around myLaw.net looking for things to do. When he finds something to do, he fails at it.)