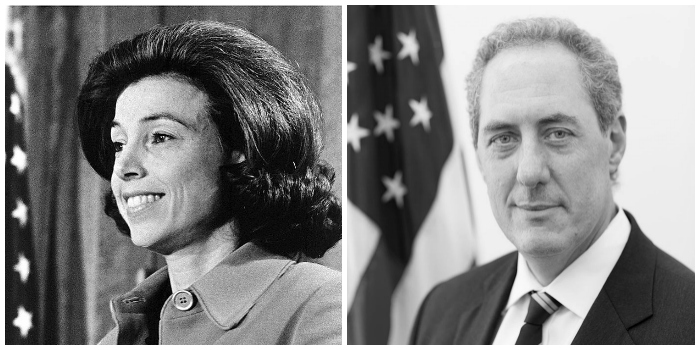

Twenty years ago, when India finally signed the Agreement on Trade Related aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (“TRIPS”), it did so after several years of arm-twisting by “Crowbar Carla”, as Carla Hills, the then United States Trade Representative (“USTR”) was called by the media. Ms. Hills earned the moniker “crowbar” because of her diplomatic strategy of “crowbar diplomacy”. American economic might was used as a “crowbar” to pry open the closed economies of America’s trading partners.

Twenty years ago, when India finally signed the Agreement on Trade Related aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (“TRIPS”), it did so after several years of arm-twisting by “Crowbar Carla”, as Carla Hills, the then United States Trade Representative (“USTR”) was called by the media. Ms. Hills earned the moniker “crowbar” because of her diplomatic strategy of “crowbar diplomacy”. American economic might was used as a “crowbar” to pry open the closed economies of America’s trading partners.

Those days, the American economy was in dire straits with an ever-widening trade deficit, a fact attributed to two issues. The first was the common complaint amongst Americans that the rest of the world was indulging in protectionism. The second was that a significant portion of American exports were intellectual property and that a lot of trading partners did not have laws that protected American intellectual property. “Crowbar Carla” was tasked by the then American administration to use trade weapons such as “Super 301” and “Special 301” to exert pressure on trading partners to modify their trading policies under the threat of trade sanctions. Her bigger political goal was to use these trade weapons to prod countries like India to sign TRIPS without too much fuss. To the credit of the American administration, they were aware of the limits of brute political power and sweetened the deal by throwing in the offer of allowing Indians to export more textiles to the U.S. Textiles were and continue to remain one of the most lucrative exports from India earning the country its fair share of foreign currency. Given the dire straits of the Indian economy in 1990-91, it didn’t take much for “Crowbar Carla” to convince the Indians to sign the TRIPS. The Indian delegation which finally signed the deal at Marrakesh was headed by a Union Minister called Pranab Mukherjee – today he is the President of India.

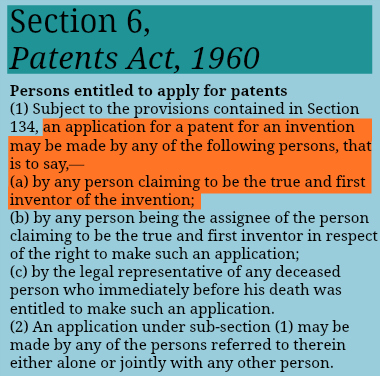

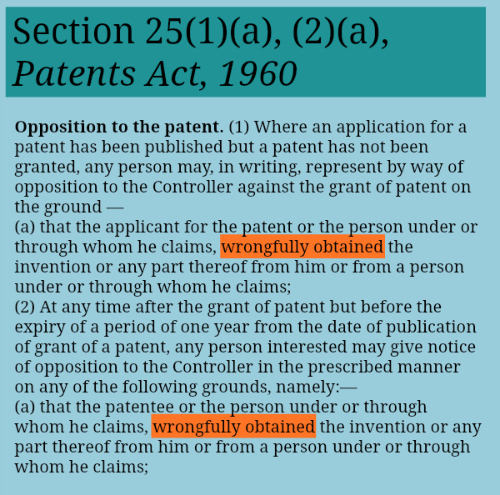

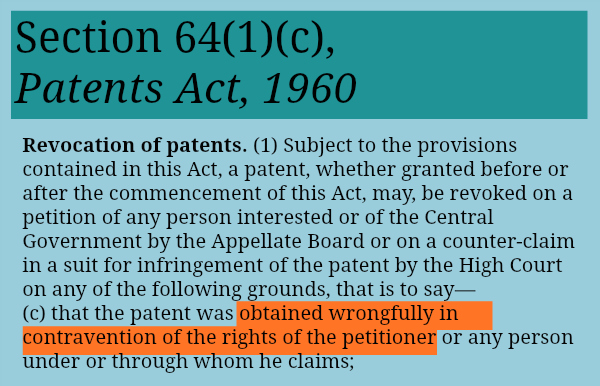

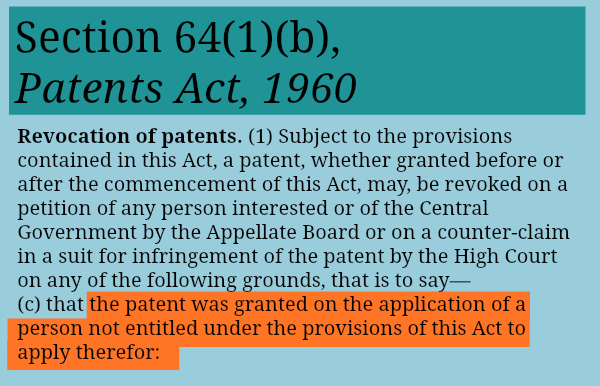

Starting with amendments in 1994 to the Copyright Act to recognise the copyright in software programs, the Indian Parliament embarked on a massive legislative agenda to introduce new intellectual property rights as was required by TRIPS. In 1999 and 2002, the NDA government amended Indian patent law. It also enacted a new law for geographical indications in 1999 and a new Protection of Plant Varieties & Farmer’s Rights Act, 2001. In 2005, it enacted the third amendment to the Patents Act, 1970 and brought back product patents for pharmaceuticals and agrochemicals after a 35-year prohibition. Each one of these new laws and amendments were a result of India signing TRIPS, an act which is directly attributable to Ms. Carla’s diplomatic prowess. With such immense powers to influence international trade policy, the USTR is certainly one of the most powerful bureaucrats in the American establishment. The question is how much has changed in the last decade? Does the incumbent USTR Michael Froman have as much power as “Crowbar Carla”?

Carla Hills (left) was the United States Trade Representative under President George H. W. Bush between 1989 and 1993. Michael Froman has held that office since 2013.

Going by news reports in the recent past, it would appear that Froman has managed to extract significant concessions from India on its intelelctual property policy. Apparently Froman, in recent testimony to American lawmakers has commented that the US is making good progress with the new Modi government on the issue of IP protection. While Froman did not provide details of the actual negotiations, there has been gossip from the civil society organisations in India that the government is going to make serious concessions such as the introduction of a data exclusivity regime for pharmaceuticals apart from a possible drug-patent linkage system. The data exclusivity regime will ensure that generics cannot rely on innovator clinical trial data for a certain timespan in order to get regulatory approvals. This will delay the introduction of generics into the market. The drug-patent linkage system on the other hand is meant to ensure that the drug regulator doesn’t provide regulatory approval to those drugs which are still under patent protection. The Drug Controller General of India (“DCGI”) had planned to introduce such a system few years ago but was forced to backtrack after a serious backlash from the manufacturers of generics. They argued that the DCGI was meant to regulate only safety and efficacy and that he was neither, equipped nor required to enforce patent rights under the law.

The big question is whether the Modi government will actually concede to these demands.

Unlike in the times of “Crowbar Carla”, the current USTR has far fewer trade weapons in his arsenal, thanks to WTO laws which place restrictions on the manner in which the US can impose trade sanctions on trading partners. The favoured weapon of the Americans in the old days was hiking up tariff barriers on the imports from foreign countries but the very rationale of the WTO system is to ensure non-discrimination in tariffs between different trading partners. It is therefore questionable whether the U.S. can get away by imposing tariff barriers on imports from India. The USTR of course can embarrass India by painting a sorry picture of the country’s intellectual property policy in its Annual 301 reports – these reports are handy tools for American lobbyists to prod lawmakers in their countries to ramp up pressure for more action. However unlike the nineties, when India was promised greater access to the American market, the American establishment doesn’t appear to be offering any carrots to the Indian government. So where is the incentive for the Modi government to make concessions to the Americans? Why would Modi risk a serious backlash from the powerful combine of the generic pharmaceutical industry and patient group? Will an administration with a strong nationalist sentiment be seen as caving into American pressure in exchange for nothing? Add to this the fact that India is now a massive importer of American defence and nuclear technology and you wonder why the Modi administration would make any concessions to the Americans.

Froman’s testimony is more likely a result of the Indians agreeing to consider the American demands. This usually means that the bureaucrats in the negotiating group will draw up notes and send them to the relevant ministries for comments. The Department of Industrial Policy and Promotion, the Health Ministry, and the Pharmaceutical Department of the Ministry of Chemicals will all express their opposition. Meanwhile, lobbyists from the generic pharmaceutical industry would have leaked the notes to the media and created a furore. The RSS and the Swadeshi Jagran Manch will register their protest. The bureaucrats in the Indo-US Trade Policy Forum will most likely cite the media furore to express their inability to accept American demands, especially when India gains nothing in return.

The cycle will then repeat itself, until the Americans find a way to actually cause economic damage to India without bombing it.

(Prashant Reddy is a Delhi-based intellectual property lawyer.)