In making and implementing new laws and policies, India’s legal system must account for one of the defining characteristics of the modern Indian state – its abundant diversity across communities, religions, languages, and a host of other indices. This is particularly true when the policy under consideration is a uniform civil code to consolidate and homogenise personal laws that govern different religions.

In making and implementing new laws and policies, India’s legal system must account for one of the defining characteristics of the modern Indian state – its abundant diversity across communities, religions, languages, and a host of other indices. This is particularly true when the policy under consideration is a uniform civil code to consolidate and homogenise personal laws that govern different religions.

The term “civil code” describes the set of laws that govern personal matters such as marriage, divorce, inheritance, maintenance, and adoption. As things stand now, different sets of personal laws govern these subjects. Hindus are governed by one set of laws, Muslims by another set, Christians by yet another, and so on. With a uniform civil code, personal laws would be homogenised and unified and made equally applicable to all citizens, irrespective of their religious or other affiliations.

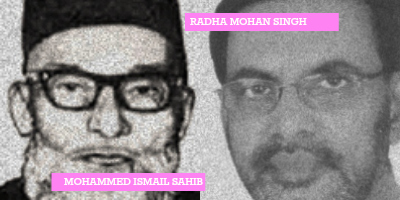

Does India need a uniform civil code? When India gained independence, the Chairman of the Drafting Committee, Dr. B.R. Ambedkar, along with several other eminent nationalists such as K.M. Munshi, Gopal Swamy Iyengar, and Alladi Krishnaswami Iyer supported the idea. Muslim fundamentalists such as Pocker Sahib, Mohammed Ismail Sahib, Hussain Imam, and Mahboob Ali Baig Sahib Bahadur on the other hand, opposed the idea. Pocker Sahib noted that imposing uniformity over all communities to override their right to follow their own personal laws in respect of marriage, inheritance, and divorce would amount to tyranny. Mohammad Ismail Sahib declared in the Constituent Assembly that:

“If anything is done affecting the personal laws, it will be tantamount to interference with the way of life of those people who have been observing these laws for generations and ages. This secular State which we are trying to create should not do anything to interfere with the way of life and religion of the people.”

Disputing arguments for uniformity of laws, he went on to argue:

“[I] maintain that for that purpose it is not necessary to regiment the civil law of the people including the personal law. Such regimentation will bring discontent and harmony will be affected. But if people are allowed to follow their own personal law there will be no discontent or dissatisfaction. Every section of the people, being free to follow its own personal law will not really come in conflict with others.”

Responding to the argument that India was simply too diverse to adopt a uniform civil code immediately, and that any such idea should be implemented only at a very distant date, Members of Parliament M.R. Masani, Hansa Mehta, and Amrit Kaur wrote:

“We are not satisfied with the acceptance of a Uniform Civil Code as an ultimate social objective. One of the factors that has kept India back from advancing to nationhood has been the existence of personal laws based on religion which keeps the nation divided into water-right compartments in many aspects of life…”

This debate happened in the backdrop of support for the theory that since Hindus and Muslims were two nations, Islam would not be free in secular India. The marked absence of consensus, combined with the prior assurances given to the Jami’at-ul-’Ulama-i-Hind by Indian National Congress leaders like Jawaharlal Nehru and Mahatma Gandhi that no Islamic laws would be abolished after independence led to the compromise of Article 44 of Constitution of India.

Article 44 declares that, “The State shall endeavour to secure for the citizens a uniform civil code throughout the territory of India.” Despite this constitutional commitment, Article 44 is only one of the several Directive Principles of State Policy, which, although aspirational and exhorted as fundamental to the governance and law making in India, are according to Article 37, neither enforceable nor justiciable in a court of law.

Sixty seven years into Independence, a uniform civil code remains an aspiration. The two most prominent national parties have pulled in opposite directions. After the BJP’s recent ascent to power at the Centre, Union Minister Radha Mohan Singh called for a discussion on the subject. Congress MP Shashi Tharoor cautioned the government against creating unpleasant divisions and bitterness in society just after the elections. Markandey Katju, the Chairman of the Press Council of India and a former judge of the Supreme Court, recently favoured the implementation of a uniform code, even going so far as to attribute the backwardness of the Muslim population to the fact that the community’s personal laws had not been modernised.

Sixty seven years into Independence, a uniform civil code remains an aspiration. The two most prominent national parties have pulled in opposite directions. After the BJP’s recent ascent to power at the Centre, Union Minister Radha Mohan Singh called for a discussion on the subject. Congress MP Shashi Tharoor cautioned the government against creating unpleasant divisions and bitterness in society just after the elections. Markandey Katju, the Chairman of the Press Council of India and a former judge of the Supreme Court, recently favoured the implementation of a uniform code, even going so far as to attribute the backwardness of the Muslim population to the fact that the community’s personal laws had not been modernised.

Clearly, devising a uniform civil code that retains only those practices, traditions, and laws that are suited to today’s the needs and discards retrograde elements is not purely a matter of legal thought and process. It is in fact an inveterately political issue, requiring careful consideration of many factors outside the law, including the sentiments of the communities involved.

Akshay Sreevatsa is an alumnus of the National Law School of India University, Bangalore and the Berekely University School of Law (Boalt Hall).

One reply on “A uniform civil code requires consideration of many factors outside the law”

I still don’t see a single persuasive benefit that accrues out of putting in place the UCC.

Any insights on possible benefits ?