http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Agx48qg1jYM&feature

The implementation in the state of Gujarat, of the Scheduled Tribes and Other Traditional Forest Dwellers (Recognition of Forest Rights) Act, 2006 (“the Forest Rights Act”), was the subject of a panel discussion at the India International Centre in New Delhi yesterday.

The distribution of land titles to members of forest dwelling communities is a key part of the law and about eight months ago, the Gujarat High Court chided the state government for not following the law while handling claims for titles. Acting on a Public Interest Litigation filed by an NGO named ARCH — Action Research in Community Health and Development, the Court ordered the state government to review all the claims to title that it had previously rejected. The Court also ordered the government to consider new types of evidence while evaluating the rejected claims and any new claims filed under this law.

Speaking on the panel, Ambrish Mehta, an ARCH trustee, placed the rights of the tribal cultivators of Gujarat in historical context. The conference was organised by the Centre for Policy Research, the Christian Michelsen Institute, and the University of Bergen.

Extracts from the edited transcript of Mr. Mehta’s talk:

Gujarat’s tribal belt, in the eastern part of the state and neighbouring Rajasthan, Madhya Pradesh, and Maharashtra, had been largely ruled by Rajput kings. These kingdoms had British residents and the land settlement processes were quite sophisticated. Technically, the tribals were tenants of the concerned jaagirdaar or similar revenue authority. They were also forced to supply labour to the jaagirdar, which was a system similar to serfdom. At that time, even though the forests were owned by the kings, local communities could influence the way they were used. The British then nationalised the forests and reached an arrangement to exploit the timber from the Dang forests in exchange for a pittance. After Independence, the forests became reserve forests. Many people — even those who were cultivating — lost their land and were instead declared encroachers. Most of the land in villages was reserve forest and the communities did not even have rights to the forest produce.

Gujarat’s tribal belt, in the eastern part of the state and neighbouring Rajasthan, Madhya Pradesh, and Maharashtra, had been largely ruled by Rajput kings. These kingdoms had British residents and the land settlement processes were quite sophisticated. Technically, the tribals were tenants of the concerned jaagirdaar or similar revenue authority. They were also forced to supply labour to the jaagirdar, which was a system similar to serfdom. At that time, even though the forests were owned by the kings, local communities could influence the way they were used. The British then nationalised the forests and reached an arrangement to exploit the timber from the Dang forests in exchange for a pittance. After Independence, the forests became reserve forests. Many people — even those who were cultivating — lost their land and were instead declared encroachers. Most of the land in villages was reserve forest and the communities did not even have rights to the forest produce.

The most serious deforestation in Gujarat also happened under the aegis of the Forest Department and in the name of scientific forest management. During the sixties and the eighties, the most productive mixed forests were felled to raise fast-growing teak plantations.

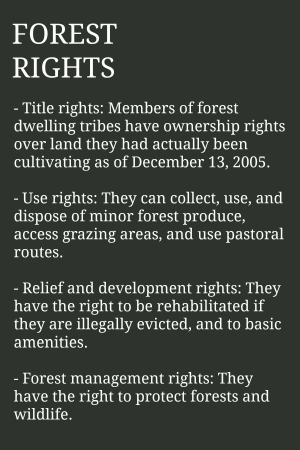

The Forest Rights Act came in this context and gave the tribals rights over the lands they were cultivating and rights over forest produce, including bamboo. They also have the right to manage forests as community forest resources.

We have been fighting an uphill battle with the state government for a proper implementation of the Act. Even though about 1,82,000 claims were filed, only 20,000 of them were approved. The rest were rejected. The Gujarat High Court held in May 2013 that all the rejected claims had to be reviewed and that all the evidence the government did not consider must be taken into account.

Previously, people did not act in the interests of the environment because they did not own anything. Once the rights came, they immediately started not only improving their land but also protecting and regenerating the forests. In many areas, there are forest regeneration committees. The enthusiasm had dipped when the government rejected their claims but now, with the judgment of the High Court, people are once again taking steps to improve their land and their cultivation.

(Aju John is part of the faculty on myLaw.net.)