Shareholders’ agreements govern the rights and obligations of the shareholders. The company is also made a party to such agreements so as to make it binding on the company. Among other things, they set out the various rights of shareholders and provide for the conduct of business, the transfer of securities, and how to resolve deadlocks. Often, the company is also made a party to such an agreement and in an investment transaction, this is done at a “closing” by holding board and shareholders’ meetings that result in the amending of the original articles of association.

Shareholders’ agreements govern the rights and obligations of the shareholders. The company is also made a party to such agreements so as to make it binding on the company. Among other things, they set out the various rights of shareholders and provide for the conduct of business, the transfer of securities, and how to resolve deadlocks. Often, the company is also made a party to such an agreement and in an investment transaction, this is done at a “closing” by holding board and shareholders’ meetings that result in the amending of the original articles of association.

Governance rights

These rights set out the level of control that a private equity investor may exercise in the management of the target company.

The common methods of exercising control include:

– the ability to appoint the investor’s representatives to the board

The number of such representatives depends on the level of investment. In cases where the number of representatives is less than 50 per cent but more than 20 per cent, the investor attempts to ensure that the quorum required for any meeting cannot be complete without some or all of its representatives present and voting.

Where the parties cannot agree on such compulsory quorum requirements, a list of “affirmative vote” items is set out. These are items that the board cannot take a decision on without the investor’s consent. Some common “affirmative vote” items include entering into key agreements, the appointment of key personnel, the incurring of indebtedness and creation of security, and bringing about any changes to the business. How comprehensive this list of items is, also depends on the negotiations and the investment. For most startups, the investment is low and their independence in relation to the operations of the business is often instrumental to a transaction. Achieving a balance between such independence and the security of investment is a key point in the negotiations.

– provision of voting rights

In most cases, since the money is routed through a tax-friendly jurisdiction, investment is made in the form of compulsorily convertible instruments with a conversion pricing formula. This means that the instrument shall convert into equity at a later time (with a specific conversion event that should be clearly set out) under a formula that the parties agree on.

Until recently, it was assumed in the agreement that the instruments have already been converted into equity. The proportion of the investors’ (assumed) holding in the entire shareholding of the company would entitle the investor to exercise higher voting rights. After recent amendments to the company law however, only equity shareholders are entitled to vote. It is not clear whether convertible instrument holders can exercise their right to vote in the company. This may have substantially curtailed the voting rights of private equity investors. So while it may be safe(until challenged) to retain in the agreement, voting rights on the basis of an assumed conversion, there may even be a case to increase control at the board level until there is more clarity in the law.

Anti-dilution rights

Usually, in any investment transaction, it is stipulated that if the company carries out a share split, issue of bonus shares, consolidation of shares, combinations, recapitalisations or any similar event that may result in the dilution of the shareholding of the investor, including the issuance of any securities by the company, then the investors will be protected against any dilution of its shareholding in the company. For instance, it may be provided that the company shall take all necessary steps (including but not limited to the issuance of new shares) to ensure that the investors maintain their shareholding at the level prior to the occurrence of such event, without any consideration. However, in a case where there is additional funding required by the company and a party provides for such funding without a similar contribution by the other party, dilution of the non-contributing party cannot be avoided.

Transfer of securities and exit mechanism

At the time of investment, the terms of exit are also clearly set out in the transaction documentation. Sometimes, in a joint venture or a private equity investment, some restrictions are placed on a party’s right to transfer shareholding because their involvement in the company has some value that is not monetary alone. The common forms of restrictions placed on the transfer of securities are lock-in, right of first refusal or offer, tag along rights, and drag along rights. Further, unless there is a sale of the entire shareholding of the company to a competitor, a part of the shareholding is not permitted to be sold to a competitor.

Lock-in refers to a period following the closing of a transaction during which the investor will not be able to sell his shares to a third party. This restriction is essential to maintain a sense of continuity and settlement to the business. In private equity transactions, the investor is not the person who intends to run the business of the company. It invests in the capabilities of the promoters to run the business in a particular manner. In some cases, the involvement of the promoters is key to business and it is not ideal if the promoters divest their shareholding and cease to be a part of the business mid-way through the investment cycle. Therefore, a private equity investor will usually require an undertaking from the promoters that they will not exit from the business of the company, including through the selling of any shares.

Rights of first refusal or offer, and tag along and drag along rights are particularly important when either party wishes to sell its stake to a third party. Prior to the conclusion of such a sale, any of these restrictions in the shareholders’ agreement will require the selling party to offer its shareholding, first to the other shareholder party at a price at which it was contemplating the sale to a third party. In several cases, the selling party provides the other shareholder party an offer at which a third party is ready to purchase its shares. The shareholder party then gets a right to either accept or refuse such offer. Upon a refusal, the selling party is free to sell those shares to a third party but not at a price lower than the price that was offered or provided to the other shareholder party.

Sometimes, when the sale of shares to a third party is acceptable, the other shareholder party is also entitled to sell its stake along with the selling party to such third party. It is often the case that when the promoter sells its stake to a third party, the investor is no longer keen to be in the company or may not be keen to maintain such a high stake in the company any longer and may “tag” its shares along for sale to the third party. This is usually when the promoter retains some shareholding in the company.

The sale of an entire shareholding (known as a buyout) is usually governed by different terms and the provision of drag along rights are very common in such cases. Drag along rights refer to a right where a selling shareholder is entitled to drag the shares of the other shareholder and sell them to a third party at the same price and terms as that of its shares.

Exit rights

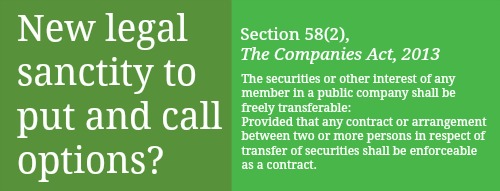

In mature private equity transactions, the investor is provided a basket of exit rights including taking the company to an initial public offer where preference is sometimes given to investors’ shares. There may also be provisions for the protection of investors’ money when things go wrong with the target company, a consideration that also influences the investor’s choice of instrument. In private equity transactions, usually, an internal rate of return or a pricing formula based on an acceptable manner of share valuation is determined at the very outset. At the time of exit, a put option is provided to the investor through which it can sell its shareholding to the promoter this pre-determined valuation. On some occasions, parties also have a call option where the other party’s shares may be purchased at a pre-determined value.

Angira Singhvi is a Partner with Khaitan & Khaitan and handles general corporate, joint ventures and private equity investments.