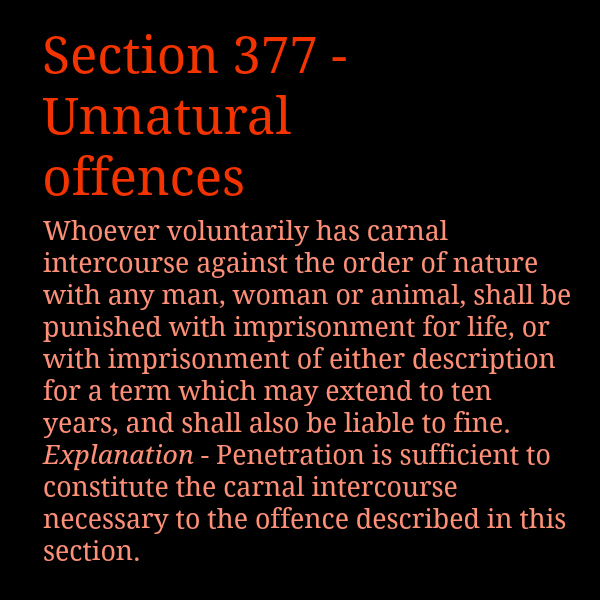

Confusion, shock, and anger continue to simmer in light of the Supreme Court’s judgment in Suresh Kumar Koushal and Another v. NAZ Foundation and Others that “Section 377 IPC does not suffer from the vice of unconstitutionality and the declaration made by the Division Bench of the High court is legally unsustainable.”

Confusion, shock, and anger continue to simmer in light of the Supreme Court’s judgment in Suresh Kumar Koushal and Another v. NAZ Foundation and Others that “Section 377 IPC does not suffer from the vice of unconstitutionality and the declaration made by the Division Bench of the High court is legally unsustainable.”

The effect of the judgment is to sustain previous judicial interpretations of the phrase “carnal intercourse against the order of nature”. As a result, any “carnal intercourse” (which by definition involves penetration) other than penile-vaginal intercourse is ‘against the order of nature’, and constitutes an offence under Section 377, Indian Penal Code, 1860.

On the face of it, such criminality attaches equally to both heterosexual and homosexual activity. The latent legal consequence is that male homosexuality is criminalised without exception due to the impossibility of penile-vaginal intercourse.

On the face of it, such criminality attaches equally to both heterosexual and homosexual activity. The latent legal consequence is that male homosexuality is criminalised without exception due to the impossibility of penile-vaginal intercourse.

Apart from compelling philosophical and practical arguments for decriminalising male homosexuality, there has also been an outpouring of a rhetoric of outrage in the immediate aftermath of the judgment — which may not necessarily convince anyone who is not already a sympathiser!

This three-part article aims to provide a reasoned contribution to the debate from a legal perspective, concluding that the judgment is very much in error. Part I compares how the High Court and the Supreme Court addressed the issue of equality under Articles 14 and 15. Part II contrasts the judgments in the context of the right to life and personal liberty under Article 21. Part III addresses two ‘red herrings’ which have occupied some of the discussion following the judgment, although not forming the substance of the debate.

So, what happened?

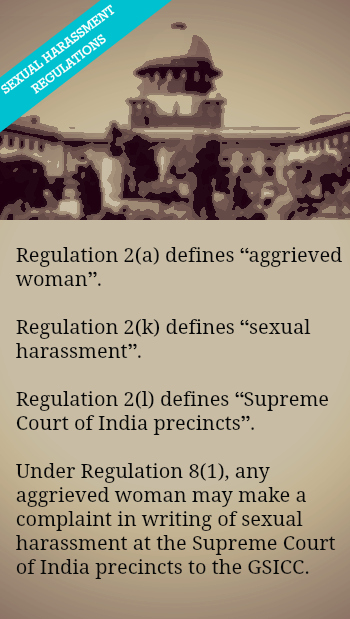

On 2 July 2009, the High Court of Delhi declared “that Section 377 IPC, insofar it criminalises consensual sexual acts of adults in private, is violative of Articles 21, 14 and 15 of the Constitution. The provisions of Section 377 IPC will continue to govern non-consensual penile non-vaginal sex and penile non-vaginal sex involving minors.”

This means that carnal intercourse between consenting adults in private would have been outside the scope of the phrase ‘against the order of nature’, and therefore, not punishable under Section 377. The Supreme Court has disagreed.

Summary of the judgment of the High Court in relation to equality:

After taking note of previous judgments in relation to Section 377, the High Court reasoned that “It is evident that the tests for attracting the penal provisions have changed from the non-procreative to imitative to sexual perversity.” The issue was whether Section 377 should include sexual acts performed by consenting adults in private (and in particular the legality of male homosexuality). Relying on judgments from India and other jurisdictions, the Constituent Assembly Debates, scholarly works, the 172nd Report of the Law Commission recommending deletion of Section 377, and various international human rights documents, the High Court held such acts to be outside the purview of Section 377, as otherwise Section 377:

– Violates Article 14 resulting in irrational classification having no nexus with the object of the law – it was argued that the object of Section 377 was to protect women and children, prevent the spread of HIV/AIDS, and enforce societal morality against homosexuality. These arguments were rejected as consensual private acts between adults have no connection with the protection of women and children, criminalisation increases health risks instead of preventing spread of HIV/AIDS, and moral norms cannot be enforced by the state on individuals if no harm is caused to anyone else or society.

– Violates Article 14 by targeting male homosexuals specifically, although Section 377 is ostensibly worded without reference to sexual orientation. It makes criminals out of all male homosexuals as a class, as the nature of the activities proscribed bears an unavoidable correlation with that class, which is arbitrary and unjust.

– Violates Article 15 as ‘sexual orientation’ is a ground analogous to ‘sex’, within the meaning of Article 15, which prohibits discrimination solely on the basis of such grounds. The High Court adopted the standards of ‘strict scrutiny’ and ‘proportionality review’ of laws, in cases where rights of a particular class were taken away on the basis of a prohibited ground. Using these standards, Section 377, if interpreted to include male homosexuality, would violate the Constitution.

The High Court noted that, given the other conclusions it had reached, it was not necessary to deal with the issue of the violation of Article 19(1)(a) to (d). Employing the doctrine of severability, Section 377 was ‘read down’ to include only non-consensual penile-non-vaginal sex and penile-non-vaginal sex involving minors.

Therefore, there were three distinct grounds (highlighted in bold above) in relation to equality on the basis of which the High Court interpreted Section 377 to exclude carnal intercourse between consenting adults in private. In order to set aside the judgment of the High Court, it was necessary for the Supreme Court to conclude that each of these grounds was fallacious.

Analysis of the Supreme Court judgment in relation to equality (Paragraphs 38 to 44 and 50 to 51)

The judgment of the Supreme Court discusses previous cases in relation to Section 377 and states (Paragraph 38):

“However, from these cases no uniform test can be culled out to classify acts as “carnal intercourse against the order of nature”. In our opinion the acts which fall within the ambit of the section can only be determined with reference to the act itself and the circumstances in which it is executed. All the aforementioned cases refer to non consensual and markedly coercive situations and the keenness of the court in bringing justice to the victims who were either women or children cannot be discounted while analyzing the manner in which the section has been interpreted. We are apprehensive of whether the Court would rule similarly in a case of proved consensual intercourse between adults. Hence it is difficult to prepare a list of acts which would be covered by the section. Nonetheless in light of the plain meaning and legislative history of the section, we hold that Section 377 IPC would apply irrespective of age and consent.” (emphasis supplied)

It is not difficult to see why a uniform test has not evolved – the words in the provision are in the realm of metaphor, or at best, subjective opinion. The first and last sentences of the above paragraph are directly in conflict. If Section 377 has a ‘plain meaning’, a uniform test should be decipherable from the section itself. In any case, it is acknowledged that even judicial interpretation has not provided a uniform test for the applicability of the section. The absence of a uniform test implies arbitrariness. If at all a ‘core’ meaning of the section can be identified, it has to be restricted to cases of “non consensual and markedly coercive situations”, which is precisely what the High Court had done.

Paragraphs 39 to 41 and 51 of the judgment assert that the factual foundation necessary for the challenge to the constitutionality of the law was not established and that discrimination or abuse of a law cannot be presumed. According to the judgment, the facts pleaded by Naz Foundation “are wholly insufficient for recording a finding that homosexuals, gays, etc., are being subjected to discriminatory treatment either by State or its agencies or the society.”

Whether the pleadings were insufficient for such a finding to be reached is a question that permits some subjectivity, although it is relatively unusual for the Supreme Court to make a factual assessment anew in an appeal under Article 136. The reasoning in those paragraphs of the judgment is fallacious because the challenge under Article 14 did not require a factual foundation of that nature to be established. The challenge was based on the presence of an irrational classification in the law without a nexus with its object, not particular instances of discrimination by state agencies.

Paragraph 42 states “Those who indulge in carnal intercourse in the ordinary course and those who indulge in carnal intercourse against the order of nature constitute different classes and the people falling in the latter (sic) category cannot claim that Section 377 suffers from the vice of arbitrariness and irrational classification… Therefore, the High Court was not right in declaring Section 377 IPC ultra vires Articles 14 and 15 of the Constitution”

Although Article 15 is mentioned, the challenge under Article 15 based on the prohibition of discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation is not addressed.

As far as Article 14 is concerned, in a case where the challenge is based on the constitutionality of male homosexuality being classified specifically as ‘against the order of nature’, it is no answer that the existence of such classification itself means that it is not arbitrary. According to this logic, there would never be any cases of irrational classification as long as such classification exists.

The conclusion of the argument is that classification under Section 377 is not irrational. The assumption of the argument is that classification under Section 377 is not irrational. This is, by definition, a tautology.

Paragraph 43 states that “a miniscule fraction of the country’s population constitute lesbians, gays, bisexuals or transgenders and in last more than 150 years less than 200 persons have been prosecuted (as per the reported orders) for committing offence under Section 377 IPC and this cannot be made sound basis for declaring that section ultra vires the provisions of Articles 14, 15 and 21 of the Constitution”.

According to the Constitution, fundamental rights do not admit of exceptions solely on the ground that the class of people affected is a minority. Imagine laws that would label people as criminals if they were left-handers, or atheists, and the flaw in such reasoning is apparent (although criminalising this does not sound so unreasonable, eh? What about vegetarians?). Those who support criminalisation of homosexuality under Section 377 must justify how a person’s sexuality — a private facet of that person’s life — enables them to cast a moral judgment about that person as a whole, and render that person liable to imprisonment for life.

As a distinct point, it is disconcerting that the judgment only considers the 200-odd who have been prosecuted under Section 377 as affected, and not the 25 lakh men who have sex with men in India whose sexuality is labelled criminal (2006 Government estimate quoted in the judgment).

In Paragraph 44, by citing two previous decisions, the judgment seeks to argue that the vagaries of language and the scope for interpretation of a penal provision by itself would not render the provision arbitrary. It is implied that the ‘against the order of nature’ cannot be arbitrary merely on the ground that it can be interpreted to mean different things. However, this does not answer any of the challenges to Section 377 under Articles 14 and 15. There is no legal basis to conclude that an interpretation contrary to these fundamental rights can be sustained.

(Students of jurisprudence will probably afford themselves a wry smile at the irony of the argument in Paragraph 44 of the judgment being a strand of the idea of the inevitable ‘open texture of law’, an idea developed by the jurist H.L.A. Hart, who also formed one half of the Hart-Devlin debate.)

The second part of this article will compare the arguments in relation to life and personal liberty (Article 21).

(Aditya Verma practices as an Advocate at the Supreme Court of India. He is an alumnus of NLSIU, Bangalore, and is on the roll of solicitors in England and Wales.)