I had referred to the Sulamerica decision a couple of weeks ago in the context of inconsistency in drafting arbitration agreements. There, the contract in question contained both an exclusive jurisdiction clause (to the courts in Brazil) as well as arbitration clauses referring disputes to arbitration in London. While the inconsistency issue was resolved (in favour of the arbitration agreement) in the High Court itself, the Court of Appeal had to be brought in to decide another critical question — what was the proper law of the arbitration agreement in the absence of an express choice by the parties?

I had referred to the Sulamerica decision a couple of weeks ago in the context of inconsistency in drafting arbitration agreements. There, the contract in question contained both an exclusive jurisdiction clause (to the courts in Brazil) as well as arbitration clauses referring disputes to arbitration in London. While the inconsistency issue was resolved (in favour of the arbitration agreement) in the High Court itself, the Court of Appeal had to be brought in to decide another critical question — what was the proper law of the arbitration agreement in the absence of an express choice by the parties?

Most of us know that as a consequence of the doctrine of separability, the law governing the arbitration agreement need not be the same as either the governing law of the contract or the law of the seat of arbitration. Most of us also know the importance of the law governing the arbitration agreement – it decides issues concerning the scope, validity, and interpretation of the arbitration agreement.

In spite of its importance however, arbitration clauses rarely specify the law governing the arbitration agreement. Even though they should. This is especially so because courts in different jurisdictions have not been consistent at all on how to decide, in the absence of an express choice made by the parties, which law governs the arbitration agreement.

In spite of its importance however, arbitration clauses rarely specify the law governing the arbitration agreement. Even though they should. This is especially so because courts in different jurisdictions have not been consistent at all on how to decide, in the absence of an express choice made by the parties, which law governs the arbitration agreement.

The governing law (of the contract) approach

Older English decisions had held that in the absence of an express choice made by the parties, the law governing the arbitration clause would follow the governing law of the underlying contract. It was implied, they felt, that the parties intended for their express choice of governing law to also govern the arbitration clause.

Indian decisions also followed this approach (see the Supreme Court’s decision in N.T.P.C. v Singer (1994). Only where the parties did not specify either the governing law of the contract or the law governing the arbitration agreement would a presumption arise that the latter follows the law of the seat of arbitration.

The law of the seat approach

Recent English decisions (such as C v. D, [2007] EWCA Civ 1282) however, seem to favour the objective “closest and most real connection” test in deciding the proper law of the arbitration agreement, which invariably leads to the law of the seat of arbitration.

In Sulamerica, the governing law of the insurance policy was Brazilian law while the arbitration was English-seated. The law governing the arbitration agreement was not specified. The High Court, following other recent English decisions, held that the proper law of the arbitration agreement was English law because it had its closest and most real connection with the law of the seat.

This decision was appealed on the ground that the High Court judge should have held that the parties had made an implied choice of Brazilian law as the proper law of the arbitration agreement (following their express choice of Brazilian law as the governing law of the contract).

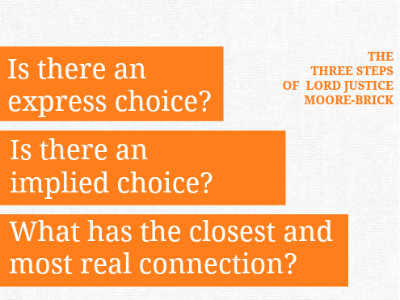

The Court of Appeal dismissed the appeal. Lord Justice Moore-Bick stated that the proper law was to be determined by undertaking a three-stage enquiry.

The test

First, look into the express choice of the parties, if any. If this did not exist, then the courts should turn to the implied choice of the parties, and if this could not be determined, the courts should determine the system of law with which the arbitration agreement had its “closest and most real connection”.

First, look into the express choice of the parties, if any. If this did not exist, then the courts should turn to the implied choice of the parties, and if this could not be determined, the courts should determine the system of law with which the arbitration agreement had its “closest and most real connection”.

No implied choice

There was no express party choice in Sulamerica, so Lord Justice Moore-Bick went on to consider the implied choice of the parties. He said that “in the absence of any indication to the contrary”, an express choice of law governing the substantive contract was a strong indication that implied the choice of the same law in relation to the agreement to arbitrate; unless of course “there are other factors present which point to a different conclusion.”

Two important factors in this case indicated that the parties had not impliedly chosen Brazilian law to govern the arbitration agreement. The first was the choice of London as the seat, and second was the fact that a choice of Brazilian law meant that the arbitration agreement was enforceable only with the insured’s consent (which, according to the court, the parties could not have intended!).

Law of the seat has the closest and most real connection to the arbitration agreement

Because there was no express or implied choice of the law governing the arbitration agreement, he then went on to consider which system of law the arbitration agreement had the closest and most real connection. The court determined that the arbitration clause had its closest and most real connection with the law of the seat, that is, English law.

It is interesting to note Lord Justice Moore-Bick’s words in this regard. You may disagree with this assessment, but to me, it almost seems as if once the enquiry proceeds to the third stage, it will be the law of the seat that will almost always have the closest connection to the arbitration agreement.

“… No doubt the arbitration agreement has a close and real connection with the contract of which it forms part, but its nature and purpose are very different. In my view an agreement to resolve disputes by arbitration in London, and therefore in accordance with English arbitral law, does not have a close juridical connection with the system of law governing the policy of insurance, whose purpose is unrelated to that of dispute resolution; rather, it has its closest and most real connection with the law of the place where the arbitration is to be held and which will exercise the supporting and supervisory jurisdiction necessary to ensure that the procedure is effective. Its closest and most real connection is with English law. I therefore agree with the judge that the arbitration agreement is governed by English law.”

Lord Neuberger’s observations – back to the High Court’s approach?

In Sulamerica, Lord Neuberger agreed with Lord Justice Moore-Bick’s three-stage enquiry. However, while referring to C v. D, he added the following observations:

“….there are a number of cases which support the contention that it is rare for the law of the arbitration to be that of the seat of the arbitration rather than that of the chosen contractual law, as the arbitration clause is part of the contract, but …the most recent authority is a decision of this court which contains clear dicta (albeit obiter) to the opposite effect, on the basis that the arbitration clause is severable from the rest of the contract and plainly has a very close connection with the law of the seat of the arbitration.”

Again, you may disagree with this analysis, but it seems to me that he gives precedence to the ‘close connection’ test (over the parties’ implied choice) on the basis of the doctrine of separability (unlike Lord Justice Moore-Bick who resorted to the third step only because there was no implied choice).

Subsequent application of the three-step test

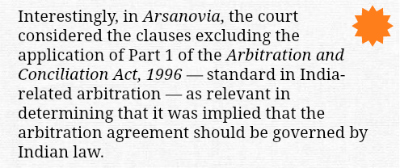

However, it is Lord Justice Moore-Bick’s three-step test that has been applied since Sulamerica. In Arsanovia Ltd v. Cruz City 1 Mauritius Holdings, [2012] EWHC 3702 (Comm), which involved Indian governing law and an English seat, Justice Andrew Smith (in the High Court) applied the three-step test and concluded that as a matter of contractual interpretation, the parties had demonstrated their mutual  intention that the arbitration agreement be governed by the law of India. Because the judge was able to determine the implied choice of the parties in this case, there was no need to resort to the closest and most real connection test (which, according to him, would have been the law of the seat).

intention that the arbitration agreement be governed by the law of India. Because the judge was able to determine the implied choice of the parties in this case, there was no need to resort to the closest and most real connection test (which, according to him, would have been the law of the seat).

It will be interesting to see how Indian courts apply these decisions. The recent English decisions do not give a whole lot of certainty as to the principles that should be followed in determining the proper law of the arbitration agreement, and it will be interesting to see if Indian courts adopt the C v. D — Lord Neuberger reasoning and give precedence to the law of the seat, Lord Justice Moore-Bick’s three step test, or come up with a completely different line of reasoning.

In any case, the drafting lesson here is clear – specify the law governing the arbitration agreement. With the uncertainty on the law in this area, it seems safest to think about and solve the problem at the drafting stage itself.

(Sindhu Sivakumar is part of the faculty on myLaw.net.)