It is commonly believed about the Indian patent regime that the first person to file an application to patent an invention is the one entitled to the patent on it. The letter of the law however, does not seem to support this belief. No matter how pedantic it may seem, the interpretation of a statute must begin with the language of the provision and must not be driven by what we think the law is or ought to be.

It is commonly believed about the Indian patent regime that the first person to file an application to patent an invention is the one entitled to the patent on it. The letter of the law however, does not seem to support this belief. No matter how pedantic it may seem, the interpretation of a statute must begin with the language of the provision and must not be driven by what we think the law is or ought to be.

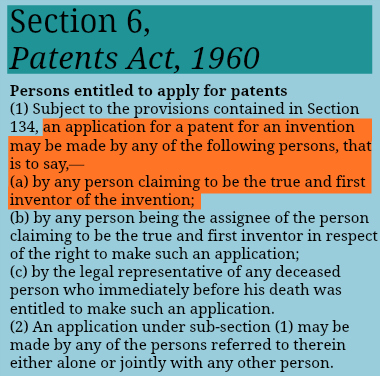

Section 6 of the Patents Act, 1970 (“Patents Act”) which governs the entitlement of a person to file an application for a patent, is extracted below.

Thus “any person claiming to be the true and first inventor of the invention” may file an application for a patent. The provision uses the words “true” and “first”, and in that order. This means the person (or persons, where there are multiple inventors) must have invented the invention without free-riding on the efforts of another person. Secondly, that person must also be the first one to truly invent the invention. Nowhere does the provision convey a “first to file” rule, where the entitlement is based on prior filing.

The requirements under Section 6 are conjunctive, that is, “true” and “first”. So even if the person’s claim of being the inventor is true, it is possible that he may not be the first inventor. It is only his belief or claim that he is the first inventor because no one has— to the best of his knowledge — published the invention in the public domain or filed for a patent.

That belief could, however, be misplaced. Another person may be able to prove that he was not only the true inventor, but also the first. Can a claim that a person was the true and first inventor be rebutted? Does the Patents Act provide for a remedy that can be invoked to prove “true and first” inventorship?

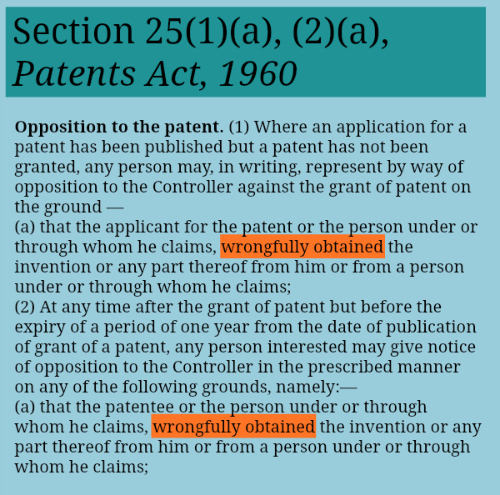

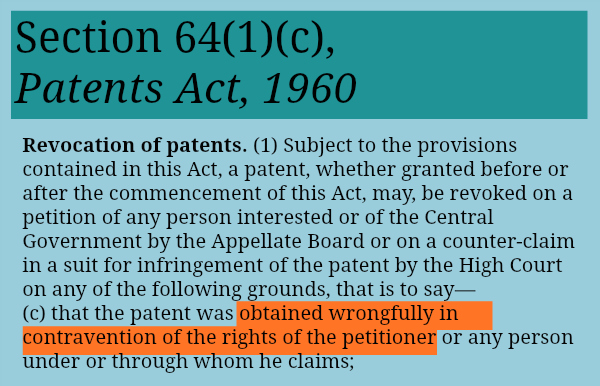

My understanding is that there is no such remedy under the two opposition mechanisms (before grant and after grant) in Section 25(1)(a) and Section 25(2)(a). Both refer to an invention that has been “wrongfully obtained”. Even Section 64(1)(c), which deals with the revocation of patents, considers a similar scenario where the true inventor has been defrauded by another person who has applied for a patent or who has been granted one. In other words, these provisions deal with situations where the patent applicant or patentee is not the “true inventor” since he has obtained the invention “wrongfully”. If the true inventor’s challenge under these provisions is successful, the patent application or patent shall be transferred to his name pursuant to Sections 26 and 52 respectively.

My understanding is that there is no such remedy under the two opposition mechanisms (before grant and after grant) in Section 25(1)(a) and Section 25(2)(a). Both refer to an invention that has been “wrongfully obtained”. Even Section 64(1)(c), which deals with the revocation of patents, considers a similar scenario where the true inventor has been defrauded by another person who has applied for a patent or who has been granted one. In other words, these provisions deal with situations where the patent applicant or patentee is not the “true inventor” since he has obtained the invention “wrongfully”. If the true inventor’s challenge under these provisions is successful, the patent application or patent shall be transferred to his name pursuant to Sections 26 and 52 respectively.

However, an allegation that an invention has been “wrongfully obtained” under Sections 25(1)(a), 25 (2)(a), and 64(1)(c) is distinct from the issue under discussion, namely a situation where the patent applicant has not committed fraud, but is merely under the factually misplaced yet genuine belief that he is the “true and first inventor”.

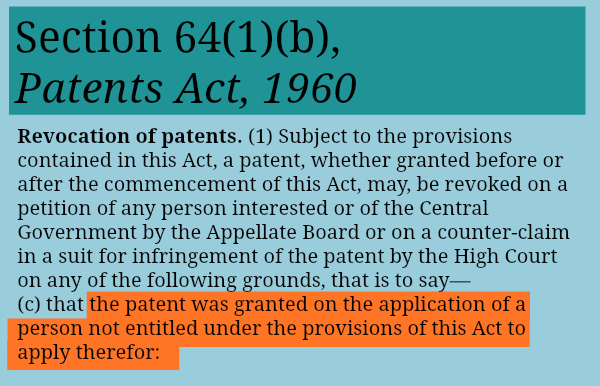

My reading of the Patents Act is that the remedy for such a situation lies in Section 64(1)(b) which provides for a ground of revocation based on “entitlement to apply for a patent”. This, in my opinion, is a reference to Section 6, which lists who is entitled to apply for a patent.

To cut a long story short, while Section 64(1)(c) addresses an allegation of the invention being “wrongfully obtained”, Section 64(1)(b) addresses a situation where a person challenges the grant of a patent because he is the “true and first inventor”. Therefore, X, who believes that Y ought not to have been granted a patent since X conceived of the invention before Y who is merely the first filer of the patent application, has a remedy under Section 64(1)(b). Surprisingly, such a remedy has not been provided for under the scheme for opposition in Section 25(1) and 25(2), before and after the grant of a patent. Consequently, X has to wait until a patent is granted in order for him to challenge its grant under Section 64(1)(b).

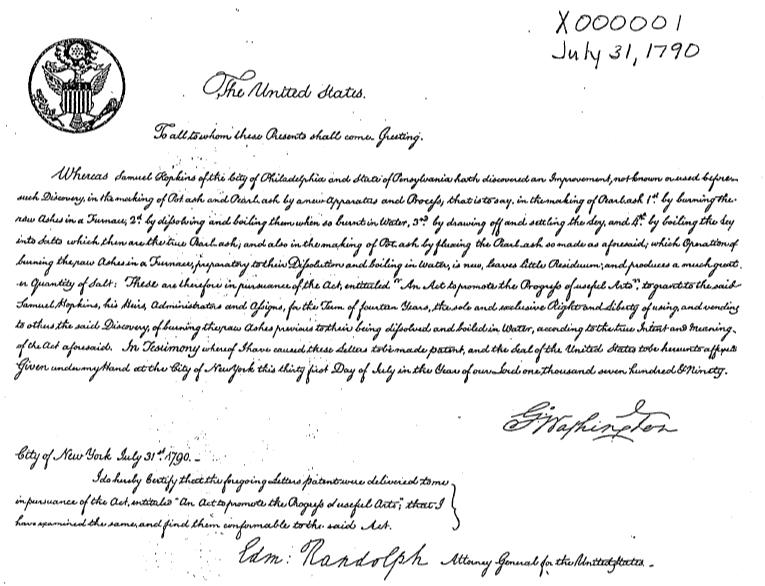

From the above, what is certainly clear is that the Patents Act has a “first to invent” rule, and not a “first to file” rule. Despite the clarity in the statutory framework, it is indeed intriguing that most people assume that India follows the “first to file” rule. Finally, the policy argument against the “first to file” rule is that if the “true and first inventor” does not wish to file for a patent and instead wishes to protect the invention as a trade secret, or intends to freely share the invention with the public, another person should not be granted a patent merely because he is the first to file an application for it.

(J. Sai Deepak, an engineer-turned-litigator, is a Senior Associate in the litigation team of Saikrishna & Associates. He is the founder of “The Demanding Mistress” blawg. All opinions expressed here are academic and personal.)