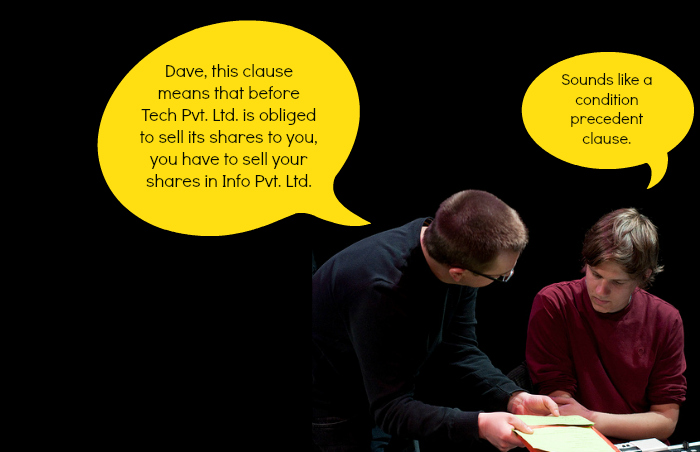

Shareholders agreements, we all know, list the rights and obligations of the shareholders in a company and contain clauses that are vital for any M&A transaction. We have already discussed one such clause, the conditions precedent clause. Let us now study another set of clauses – commonly grouped under the term, ‘transfer restrictions’.

Shareholders agreements, we all know, list the rights and obligations of the shareholders in a company and contain clauses that are vital for any M&A transaction. We have already discussed one such clause, the conditions precedent clause. Let us now study another set of clauses – commonly grouped under the term, ‘transfer restrictions’.

Consider the case of a foreign investor who intends to purchase 26 per cent of the shares of a company and has all the know-how and expertise to run the business. This investor’s participation is critical to the business and its Indian partner in the business would prefer that it does not exit the company. Even the foreign investor, mindful of its faith in the Indian partner, would not want the Indian partner to exit the company. The shareholders agreement therefore, would contain clauses that restrict the foreign investor and the Indian partner from transferring their shares to a third party. A ‘transfer restriction’, simply put, restricts shareholders from transferring their shares in the company.

All doubts about the legality of transfer restrictions under the Companies Act, 1956 has been cleared by the proviso to Section 58(2) in the Companies Act, 2013. It clearly states that “any contract or arrangement between two or more persons in respect of transfer of securities shall be enforceable as a contract”.

While there is no formal clarification from the Ministry of Corporate Affairs regarding this insertion, it appears that that this provision is an attempt to codify the principles laid down in the judgment of the Bombay High Court in the case of Messer Holdings Limited v. Shyam Madanmohan Ruia and Others, [2010] 104 SCL 293 (Bom). The Court held that it is open to shareholders to enter into consensual agreements in relation to the specific shares held by them, provided such agreements are not in conflict with the articles of association of the company, the Companies Act, 1956, and its rules. Such agreements can be enforced like any other agreement and does not impede the free transferability of shares.

The Companies Act, 2013 has also recognised the position that a share is the property of the shareholder. The shareholder is free to transfer his or her property, provided that it is not in conflict with the articles of the company and other provisions of company law.

Let us now focus on a few common transfer restrictions.

Lock-in period

By a specifying a period during which a party is prohibited from transferring or selling its shares in the company, a shareholder is ‘locked in’ to the company. This restriction can apply to one, some, or all the shareholders of in the company.

There is no specified time period applicable to all transactions. Parties determine the time period for the lock-in depending on commercial considerations such as the nature of the business. Sometimes, the time period may differ among shareholders.

The Indian party in our earlier example may feel that five years is sufficient time to absorb all the foreign investor’s know how and then run the business independently. In such a case, the Indian party would probably be content with a lock-in period of five years applicable to the foreign investor.

Right of first refusal

Sometimes, a shareholder who intends to sell its shares to a third party can only do so after first offering them to the other shareholders and only if they refuse to purchase these shares. The price at which the shares are sold to the third party must be equal to or higher than the price at which they were offered to the other shareholders. This gives the other shareholders in the company a right of first refusal, that is, a right to purchase shares which helps consolidate their own shareholding in the company and also prevent the entry of an undesirable purchaser.

Tag along right

A right is some times granted to a minority shareholder to require the majority shareholder to sell its shares along with those of the majority shareholder, to the same third party. This gives a minority shareholder, the right to exit the company if it does not want to continue in the company with a new majority shareholder.

Drag along right

While a tag along right is granted to a minority shareholder, a drag along right is typically granted to a majority shareholder. A majority shareholder will have the right, while selling its own shares, to require the minority shareholder to sell its shares as well. The majority shareholder can thus drag the minority shareholder along while making a sale.

This right is important from the perspective of a new investor. Consider the case of an investor who is about to purchase 95 per cent of the shares of a company from one party in which another party holds the remaining five per cent shares. Since a new investor would prefer to own all the shares and take full control of the company, the majority shareholder would prefer to exercise a drag along right and force the minority shareholder to sell its five per cent to the same new investor.

The key point to remember while drafting any of these clauses is that your clients (whether a majority or minority shareholder) would like to maximise their investment while exiting the company. Therefore, determining the price at which shares are sold is critical.

Say for instance, your client has a drag along right. While drafting this clause, it may be best to lay down certain principles as to how the share price will be determined to ensure that there is no dispute at a later stage. Generally, the minority shareholder sells his or her shares at the same or higher price than that which is offered by the third party for the shares of the majority shareholder.

Always be very clear while drafting these clauses. You should choose your words and terms carefully and ensure there is no ambiguity while interpreting the nature of the restriction. Remember that these clauses are primarily contractual in nature and will always change depending upon the nature of the transaction. Never cut and paste a clause from another agreement without applying your mind to the facts of your transaction. In short, put in time and effort in understanding the transaction and only then draft a clause to suit the requirements of your client.

(Deepa Mookerjee is part of the faculty on myLaw.net.)