Mohammad Ali Jinnah evokes strong responses in South Asia, and has been cast in a multitude of roles depending on which side of the political line he is viewed from – a master negotiator, a charismatic leader, a cunning politician, a secular liberal, and a conservative reactionary. Few, however, see him as a lawyer, his primary professional training that helped launch his career in public life and shaped both, his political career, and his ideological vision.

Lawyers of course, overwhelmingly dominate the galaxy of political leaders in colonial India. This was partly structural. Professional and middle classes have always played a significant role in republican movements. In British India, law, unlike medicine or engineering, was the only profession that could be practiced without being employed by the colonial government. Jinnah is unique in being amongst the handful of lawyers who became equally successful in both their fields.

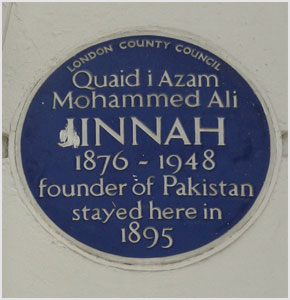

Jinnah was born into a Gujarati Khoja Muslim family engaged in trade in Karachi. As a successful trader in British India, Jinnah’s father realised that they had to forge closer links with British traders. It was to learn trade that Jinnah was sent to London. At the age of 15, he began a three-year apprenticeship with the London office of the Graham’s Shipping and Trading Company, a firm that specialised in trading in textiles and port wine. The minutiae of trade did not interest Jinnah, so within a few months of reaching England, he enrolled instead at the Inns of Court to train as a barrister. An apocryphal story suggests that his choice of Lincoln’s Inn was guided by the fact that it listed the Prophet Muhammad’s name over its doors among a list of the world’s greatest lawgivers. Jinnah’s training was purely vocational: he did not have a college education, but he passed his Bar with flying colours, graduating at the age of 19 as the youngest Indian barrister of that time.

Jinnah returned to Bombay to begin practice at the Bombay Bar on August 24, 1896. The choice of Bombay, instead of his hometown Karachi, was not surprising. Bombay was the leading city of colonial India: it was liberal and cosmopolitan, but perhaps most importantly, was the business capital of India and therefore, the centre of commercial litigation.

Unusually for a lawyer of that period, Jinnah did not begin as a pupil to someone else but started an independent practice. Indian barristers had a hard time building a practice in India, the Indian trained vakils were often hostile and litigants were indifferent to the ‘foreign qualification’. Contrary to popular perception, most Indian law students passed their exams with the help of coaches, and had a limited command over English. While they were versed in English law and procedure, they knew little about the workings of the Indian Penal Code. Moreover, much of the commercial practice was controlled by a monopoly of British solicitor firms, who had their own network of barristers.

Like today, most young lawyers in the 19th century relied on networks of family and kin to get cases. Belonging to a commercial family, it was not surprising that Jinnah’s first case came from home. At the age of 22, he represented his uncle, Ganji Walji, a Khoja merchant who another Khoja merchant had sued for the recovery of Rs.6,790/- due as interest. This litigation, when Jinnah stepped in, was ruining his father’s business.

He did find mentors in Sir Pherozeshah Mehta, a Parsi leading lawyer, and Mr. McPherson, the Advocate General of the state, both of whom allowed Jinnah to access their respective library. McPherson sought to help out a struggling barrister by nominating him to the lower judiciary. In 1900, Jinnah was appointed Third Presidency Magistrate for Bombay, a position that paid Rs.1,500/- a month, and which placed him among a handful of Indians who wielded tremendous executive power and influence. Six months after being appointed, however, Jinnah declined to continue in the position.

While he had built his practice as a civil and commercial lawyer, it was in the period following the Magistracy that he began appearing in criminal cases, often engaged by the government. Perhaps the most famous of his early cases was the murder of a Hindu seer, Sayaji Baba, by an ‘alleged lunatic’. Jinnah assisted the prosecution in proving that the accused held a grudge against the victim before the murder and thus, despite the appearance of lunacy, committed premeditated murder.

Jinnah’s career as a public advocate bloomed after he appeared as a lawyer in the ‘Caucus’ case. The case dealt with the interference of the government in the election of local judges to the Bombay Municipal Council. The Indian Councils Act had introduced limited self-government in municipalities and half the seats of the Corporation could be contested from a limited electorate of 12,000 taxpayers. The other half consisted of nominated officials. The ‘elected’ wing of the Corporation was dominated by moderate Congress politicians, including Jinnah’s mentor Pherozeshah Mehta. In 1907 the ‘caucus’ of nominated officials connived with the government and arranged the defeat of Congressmen like Mehta. Surprisingly, Mehta, a distinguished barrister himself, hired Jinnah to plead his election petition. While Jinnah won only a partial victory (Mehta was declared elected, but many of the charges against the government were not accepted), the case made Jinnah nationally famous. This was the first time the colonial government was accused of rigging elections before its own courts, and the proceedings were extensively covered in both, the English and vernacular press. This case perhaps exemplified Jinnah’s early politics, exposing the British regime’s faults and contradictions through the constitutional framework of British rule.

Compared with his contemporaries, like Gandhi, Jinnah spent a relatively short period as a ‘briefless barrister’. His eloquent speaking style and incisive arguments helped his practice grow. As Frank Moraes was to describe his courtroom manner in later years, “Few lawyers command a more attentive audience. No man is more adroit in presenting his case. If to achieve the maximum result with the minimum effort is the hallmark of artistry, Jinnah is an artist of the craft. He likes to get down to the bare bones of the brief; in stating the essentials of his case, his manner is masterly. The drab courtroom acquires an atmosphere as he speaks. Juniors crane their necks to follow every movement of this tall, well groomed figure, senior counsels listen closely; the Judge is all attention.”

Jinnah’s public prominence grew in 1916, when he appeared as the defence lawyer for Bal Gangadhar Tilak in a sedition case. Tilak had previously been convicted for sedition and had spent time in prison. Jinnah was unsuccessful in securing Tilak’s release in the District Court of Poona, but was able to have the conviction overturned at the Bombay High Court. His argument was twofold: firstly, he argued that Indians as British citizens were entitled to criticise the bureaucracy and they owed loyalty to the British crown and not the government of India; secondly, the C.I.D. had translated Tilak’s Marathi speeches incorrectly, and the English translation wrongly gave the impression of sedition. The case turned on the nuances of Marathi, a language Jinnah was unfamiliar with, but after careful study and briefing, he ably led the cross-examination of expert witnesses. Incidentally, Jinah had prepared the line of defence in this case, and the adoption of this line was a condition for this accepting the case. While presenting his bail application in 1908, Jinnah had reluctantly refused to defend Tilak in his first sedition case because of Tilak’s insistence of dictating his own line of defence.

Jinnah engaged a number of what could be termed ‘free speech’ cases, challenging the draconian press laws that were enacted during the First World War. The most prominent of these was his defence of the Bombay Chronicle, a nationalist English language daily. Jinnah, as a classical liberal lawyer, often spoke up for civil liberties, most famously attacking the colonial government in the Central Assembly over the illegality of Bhagat Singh’s trial. Since Bhagat Singh and his co-accused had refused to cooperate with the prosecution, a special ordinance was promulgated, which permitted the trial in absentia. Jinnah’s scathing attack on the government turned on the harm caused to the rule of law by this ordinance. He argued, “I say that no judge who has an iota of judicial mind or a sense of justice can ever be a party to a trial of that character and pass the sentence of death without a shudder and a pang of conscience. This is a farce which you propose to enact”. The law he pointed out failed to meet the standards that British common law demanded. Even at his most emphatic, Jinnah’s arguments were framed in legal terms.

(Rohit De is a scholar of legal history.)