Sanhita Ambast writes about international law and international relations.

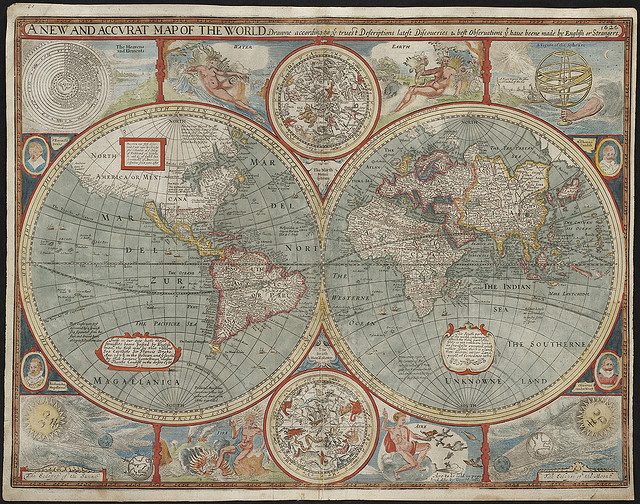

- Map Reproduction Courtesy of the Norman B. Leventhal Map Center at the Boston Public Library.

An extremely interesting enquiry today is the Indian state’s engagement with international law. Despite its growing stature in the international community, India is still not signatory to several important international instruments and does not implement several other treaties that it is signatory to. This exceptionalism warrants examination, especially when India’s oft-stated reason for not signing and complying with international law is the regime’s inherent politicisation and prevalent hypocrisy. The contest between international law and international politics is not new, and recent developments – from the war against Iraq to the failure of the Bashir arrest warrants – raise the following crucial question: is there really an international law distinct from international politics?

I hope to explore both these questions –of India’s engagement with international law and of the line between international law and politics – in a series of pieces dedicated to the result of the recent Review Conference on the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court (ICC) which took place in Kampala, Uganda earlier this year. Here the international community, by consensus, adopted a definition for the crime of aggression and agreed to a plan for its implementation. Resultant notable amendments to the Rome Statute include the definition of a ‘crime of aggression’ being linked to an ‘act of aggression … constituting a manifest violation of the United Nations Charter’ [article 8 bis]; the ability of the ICC to prosecute aggression independent of the Security Council in certain circumstances [article 15 bis]; more leeway to states in terms of accepting ICC jurisdiction and an increased role for the prosecutor.

It is interesting that that these amendments impact India’s four reasons for not signing the Rome Statute, which are explained here. First¸ India has been concerned about the wide range of powers conferred on the Security Council in the Rome Statute and the control a political body will exercise on what should be a purely legal process. This, prior to the Review Conference, included the Security Council’s monopoly over acts of aggression and article 16 of the Rome Statute (which allows the Security Council to delay ICC prosecutions indefinitely). Second, India is opposed to certain crimes under the jurisdiction of the Rome Statute – in 1998, the Rome Statute did not criminalise the use of nuclear weapons and other weapons of mass destruction. Furthermore, crimes against humanity and war crimes were defined too broadly for India’s liking and included ‘internal’ matters that should fall within the ‘domestic’ jurisdiction of states. Linked to this is India’s third objection to the Rome Statute, the idea of complimentarity and the jurisdiction of the ICC to decide when a country was ‘able and willing’ to prosecute (article 17, Rome Statute). And finally, India is suspicious about the strength of the office of the prosecutor as this power may be used in a politically motivated, arbitrary and unfair manner.

While I shall address the various impacts of the Kampala amendments in subsequent pieces, the same broad argument will run through all of them. The landscape of public international law, international humanitarian law, and international criminal law has evolved in the past decade. As a result, many of India’s concerns regarding the ICC have changed, have become irrelevant, or would be better served by engagement not boycott. This is not to say that India must sign the Rome Statute. Instead, the recent amendment to the Rome Statute, read with legal developments in the past decade, provides an important opportunity for India to reassess its policy towards the ICC, attempt reframing its objections in a more contemporary language, and consider engaging more actively with it.