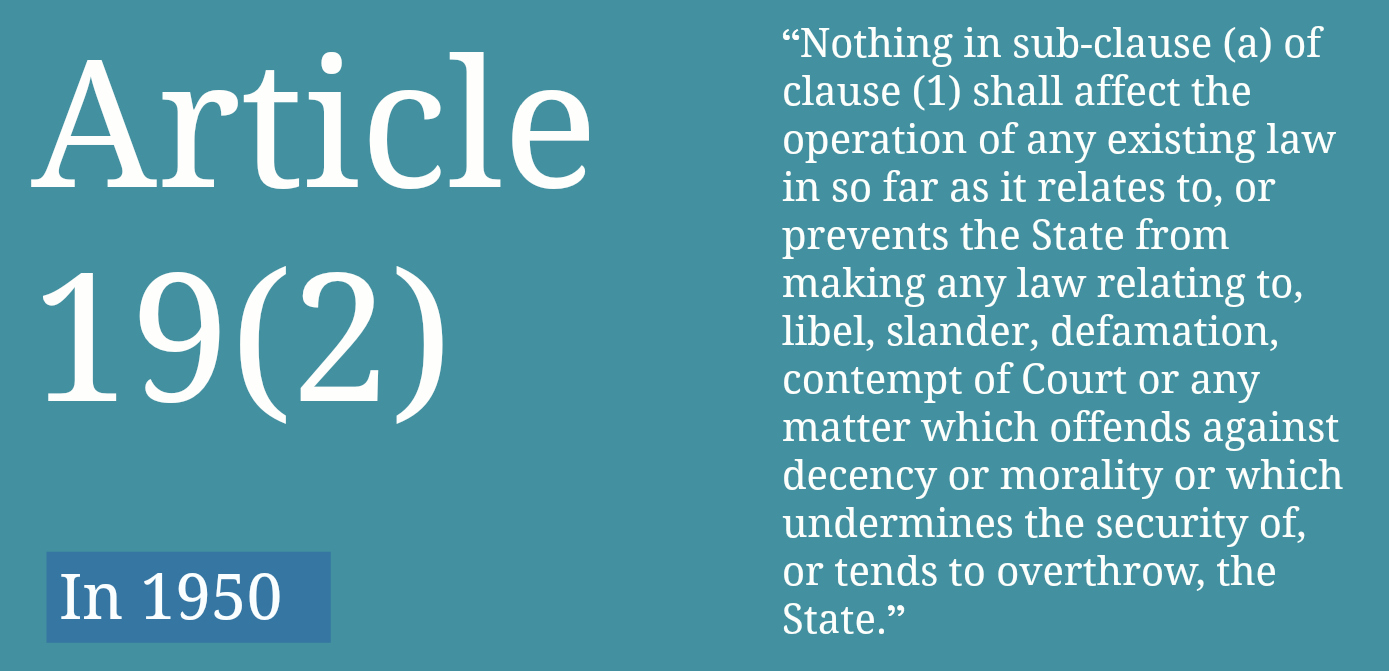

What is human rights lawyering? According to Sarim Naved, a Delhi-based advocate who has represented people accused in anti-terror cases, every criminal lawyer is in a sense a civil liberties lawyer: one could just as easily be framed and detained in a theft case as in an anti-terror one. More specifically, though, he defines the contours of a human rights or civil liberties lawyer as one who is involved with particular kinds of political cases where individuals are targeted through the criminal law because of who they are – Adivasi, Muslim, or “Naxal” – as opposed to what they have done. The State’s power in such cases renders the entire system susceptible to bias, and this is where the role of the human rights advocate comes in, to ensure that there is a fair trial and the State does not monopolise the proceeding. He clarifies that despite a very common misconception that civil liberties lawyers hate the police, most do not, and do recognise that it is a very difficult and thankless job. He said that the truth is usually somewhere in the middle of both versions, and that the trial court is the best place to determine this.

as in an anti-terror one. More specifically, though, he defines the contours of a human rights or civil liberties lawyer as one who is involved with particular kinds of political cases where individuals are targeted through the criminal law because of who they are – Adivasi, Muslim, or “Naxal” – as opposed to what they have done. The State’s power in such cases renders the entire system susceptible to bias, and this is where the role of the human rights advocate comes in, to ensure that there is a fair trial and the State does not monopolise the proceeding. He clarifies that despite a very common misconception that civil liberties lawyers hate the police, most do not, and do recognise that it is a very difficult and thankless job. He said that the truth is usually somewhere in the middle of both versions, and that the trial court is the best place to determine this.

Custodial torture presents one of the rare situations where the otherwise well laid out criminal procedure presents the victim with a choice of fora. Mr. Naved however, would always advise his clients to approach the High Court, rather than the trial courts. While a person who has been beaten or tortured by the police should ideally be able to file an FIR or approach the Magistrate and seek an inquiry, that is never done. The only option in such cases is to approach the High Court or an organisation like the National Human Rights Commission (“NHRC”).

When I met him at his Hauz Khas Enclave office to speak about human rights lawyering in the trial courts, Mr. Naved said that his few interactions with the NHRC had all been fruitful. In one such incident, he was informed that the police had picked up a group of Rohingya refugees, who were protesting outside the office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (“UNHCR”). As he was in court and unable to visit the location, he called the NHRC, who then sent the police station a notice directing them to explain their action at a hearing which would be held for the purpose. On another occasion, a fax sufficed – he did not have to meet the Chairperson or even make a visit in person.

When I met him at his Hauz Khas Enclave office to speak about human rights lawyering in the trial courts, Mr. Naved said that his few interactions with the NHRC had all been fruitful. In one such incident, he was informed that the police had picked up a group of Rohingya refugees, who were protesting outside the office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (“UNHCR”). As he was in court and unable to visit the location, he called the NHRC, who then sent the police station a notice directing them to explain their action at a hearing which would be held for the purpose. On another occasion, a fax sufficed – he did not have to meet the Chairperson or even make a visit in person.

A preference for human rights remedies at the High Courts

The speed at which a remedy can be obtained from the High Court is an important reason why Mr. Naved prefers writ remedies. Any Division Bench in a high court can take interest in a case and direct the State to provide quick responses. The same level of urgency is not possible in trial courts, because they are governed by the Code of Criminal Procedure. The trial courts also have a very heavy workload. Mr. Naved suggested that there is an impression among lawyers that one will not get bail from the trial courts for the more serious offences. Most lawyers therefore, expect that the bail application at the trial court will be dismissed and therefore treat it as a formality before approaching the High Court. He admitted however, that he has no empirical evidence that the trial courts are actually ineffective and that his faith in the constitutional courts could just be part of a self-fulfilling prophecy with lawyers refusing to approach trial courts simply because they believe that they will not be able to obtain an effective remedy.

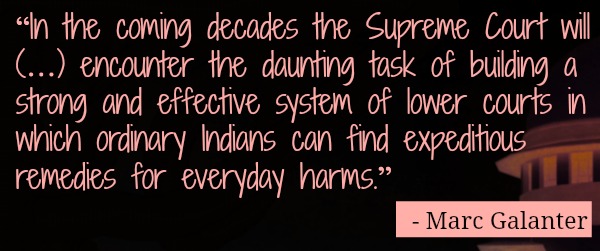

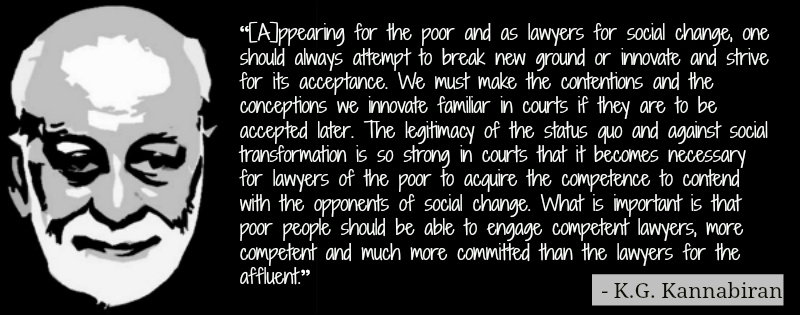

Being a relatively untested location for human rights issues, however, also means that fighting for these remedies at the trial courts requires imagination and courage of a certain kind. Says Mr. Naved, “When someone approaches you with a complaint of their rights being taken away or them being subject to various kinds of discrimination at the hands of the state, it requires a lot of courage to take a path that is not so well trodden.” Indeed, the likes of Dr. Kannabiran have shown that with persistence and conviction, it is possible to raise these questions at the trial courts, and obtain relief.

Skills on trial

That said, the importance of trial proceedings cannot be understated. “There’s only one place in this entire system where you can factually establish your case or disprove the prosecution case – and that is the trial court,” Mr. Naved said, adding that even for a completely innocent man, if the right questions are not asked at the trial court, the best of lawyers would have a hard time getting an acquittal from the higher courts, where it is only a matter of competing affidavits and the evidence is not really tested. Cases have been lost at the Supreme Court because the trial court lawyer was not very efficient. At the same time, there are notable success stories too: the acquittals of young men who were framed in terror cases described in a report by the Jamia Teachers Solidarity Association were all achieved at the trial courts.

The trial courts also require a particular set of skills—exactness, precision, the ability to think on one’s feet, and sheer determination to plough through the prosecution record, particularly in major cases such as those involving anti-terror laws, where, according to Mr. Naved, the prosecution relies on volume rather than quality of evidence. The attention to detail required while dealing with a very large amount of information, can be acquired only from a senior who has done it and will teach one to sift out relevant material from the huge volume of information, and then explain how to use it within the law. He credits his mentor, veteran advocate Nitya Ramakrishnan, for helping him develop these skills during his early days in the profession.

While defending an accused at trial, an advocate has to create a record that is favourable to the client by being present every day, making the correct decisions, and asking all the correct questions in the correct order. In contrast to an appellate setting, where the record is before the court and one knows what to say, the trial is a dialogue between the advocates, the judge, and the witnesses, and one does not know what answers to expect. The intimacy of the trial court setting also means that there is a simple level of humanity that exists there, unlike the structure of the higher courts which keeps a distance between the bench, the bar, and the client. Ultimately, Mr. Naved says of the trial courts, “It’s important to fight out battles there, because that’s the only place where everyone is face to face.”

(Manish is a legal researcher based in Delhi.)